Intergenerational Poetic-Resistance to the Neoliberal Carceral State in Mercedes Eng’s The Prison Industrial Complex Explodes: A Poem and Angela Y. Davis’s Freedom is a Constant Struggle

According to a 2021 report from Canada’s Correctional Investigator Ivan Zinger, “about 10 per cent of the federal prison population [in Canada] has been infected with COVID-19, compared to just two per cent of Canada’s general population” (Harris 2021). Zinger’s report continues to state that, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Canadian prisoners have been “confined” to “often crowded institutions” in order to “limit the spread of COVID-19”; furthermore, they have also been denied familial visits and recreation time under the guise of decreasing the “transmission of the virus” (Harris 2021). If the global coronavirus pandemic revealed anything about the neoliberal logics of North America, it was the dehumanizing treatment of people and communities deemed “disposable” by neoliberal society and politics (Giroux, Pandemic Pedagogy, 137). It is crucial, then, in this socio-political moment of instability and optimism for change, to continue to discuss and critically examine systemic mass-incarceration, the privatization of prisons, and the neoliberal dehumanization of peoples and communities. In a time of greater social isolation, different ways of connecting are necessary to maintain and create a sense of community in the face of neoliberal individualism and civil confinement. Prisons, and other spaces militarized by the prison industrial complex, are zones where this communal communication can be difficult to find or express as neoliberal-carceral methods depend on the slow degradation of these connections and communities. As Adrienne Rich defines, in the vacuum of disconnection, there is only “dead silence” and the “dead silence of senseless noise” (330); in the absence of these connections, there is only silence. Therefore, in order to collectively resist this silence, we ought to empower critical voices who are artistically connecting us during neo-liberal separation and repression. Artistic production, either in art, music, or poetry, can be this unifying force because of its use of creative compassion, which neo-liberalism works to erode. Through methods of dehumanization, individualization, and commodification of public life, neo-liberalism and its benefactors attempt to silence communal, altruistic creation and thus attempt to divide us. As Jordan T. Camp states in his book Incarcerating the Crisis: Freedom Struggles and the Rise of the Neoliberal State, “while the poetry of social movements is rarely seriously considered in debates about alternatives to neoliberalism, its significance for understanding the present moment cannot be overstated” (146). Therefore, poets, amongst other types of artists, play a crucial role in “understanding” and recording the “present moment,” and their creations can provide a way to inform and establish or maintain an ongoing critical debate and education.

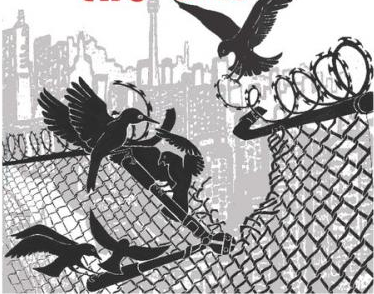

Combining both the poet’s role in creative resistance and neoliberal dissent with the confining and enforced silences of the carceral state both in and out of prisons, Mercedes Xue méi Eng’s mixed-media poetic anthology Prison Industrial Complex Explodes: A Poem provides a linkage between poetry and intimate experiences with the prison-industrial complex. As a Canadian-woman-settler poet of Chinese descent and currently located on unceded Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh territories, Mercedes Eng has both intimate and socio-political experiences with the prison-industrial complex in British Columbia, Canada. Her 2017 anthology is a collection of her own poems, compiled Canadian government documents, and, what Eng refers to as, the “state’s images and words” and “found and juxtaposed text” (Eng 101-102). Eng’s poetry directly opposes and challenges neoliberal mass-incarceration, its pervasive privatization and militarization of both public and familial spaces, and its ability to inflict intergenerational and learned harm or trauma. As critical theorist and public intellectual Henry Giroux defines in a Rolling Stones interview, “capitalism around culture is an assassin. It eliminates all that’s magical […] All that pushed the imagination” (09:34-09:47). Eng’s artistic work, like so many others, is an ongoing project to find and reclaim that imagination – that magic – from neoliberal-capitalism’s grip and its logics of commodification and dehumanization.

The term “prison-industrial complex” emerged in critical discourse and consciousness in the late 20th century as activist and cultural leader Angela Y. Davis, and other abolitionists globally, make crucial connections between the rise of economic neoliberalism, mass-incarceration, and systemic racism. In her work “Masked Racism: Reflection on the Prison Industrial Complex,” Davis writes that there are “structural similarities and profitability of business-government linkages in the realms of military production and public punishment” and therefore the “expanding penal system can now be characterized as a ‘prison industrial complex’” (1998). Taking the form of a for-profit business model, the prison industrial complex begins to economize and marketize punishment and racism against BIPOC peoples and communities. In Canada, for example, “more than 30% of inmates in Canadian prisons are Indigenous – even though [Indigenous] people make up just 5% of the country’s population” (Cecco 2020). As Davis defines in her recent book Freedom is a Constant Struggle, “racism provides the fuel” for “the prison-industrial complex” (59). Thus, prison systems rely on established settler-colonial systems of racism and white supremacy to fill for-profit prisons. Prisons, as zones of disposability, normalize the criminalization of certain communities and the militarization-incarceration of their public spaces like education and healthcare (Giroux, Pandemic Pedagogy, 78). Similarly, in Canada, BIPOC, queer, and immigrant communities are harmfully familiar with racism and police violence both in and outside of prison; for example, “once in detention […] Indigenous peoples are more likely to be sent off to maximum-security facilities and are disproportionately the recipients of harm, both self-induced and in incidents involving ‘use of force’” (Cecco 2020). Within this context of both hopeful abolitionist efforts and the impeding force of the neoliberal-carceral state, Mercedes Eng’s Prison Industrial Complex Explodes deconstructs neoliberalism’s reliance on systemic racism and the privatization of prisons and bodies while demonstrating poetic-resistance as a way to reclaim agency and resituate the power of the social collective body. Eng’s workcreatively addresses the global role of G4S private security services, the carceral state’s hand in the militarization of education and criminalization of BIPOC children, and, finally, the intergenerational impact of mass-incarceration.

In her author’s notes, Eng states that her work was partially inspired by Davis’s Freedom is a Constant Struggle (Eng 103). There is one particular poem in her anthology where Eng draws upon Davis’s outlining of the far-reaching powers of G4S global security and its role in the militarization of communities and privatization of prisons. This poem tells the story of Carole who was “inspired by an Indigenous mother” that Eng met while visiting her father in prison in Vancouver (102). Eng situates Carole as a member of a maternal collective that opposes neoliberal breakdown of society and childhood:

Carole researches

Group 4 Securicor (G4S)

the biggest private security group by revenue

the third-largest private employed

in the world

[…]

Carole laughs and cries

When she reads on the company’s website:

In more ways than you might realize,

G4S is securing your world

Carole weaves

a G4S-resistant blanket

big enough for all the babes of all the red nations. (Eng 84)

In this poem, Eng addresses G4S’s historical and current grip on society and family. Emerging in a neoliberal landscape, G4S as of 2012 “operates 20 facilities” within Canada (Price and Morris 255). In Canada, beyond the inner-workings of G4S corporation, there are also organizations developing that force public institutions to depend on private funding; for example, as Eng discusses in her author’s notes, “PPP Canada” is “a federal Crown corporation that partners with private businesses to build public infrastructure like prisons and refugee-detention centers” (101). According to Davis in Freedom is a Constant Struggle, “G4S represents the growing insistence on what is called ‘security’ under the neoliberal state and ideologies of security that bolster not only the privatization of security but the privatization of imprisonment […] as well as the privatization of health care and education” (55). We see this pervasiveness in Eng’s poem as Carole, in emotional waves, becomes overwhelmed by the security state and how it operates. As an Indigenous woman affected by mass-incarceration, G4S’s structures and policies mesh with settler-colonial ideologies as global privatization also represents the invasiveness of the carceral state in the genocidal project of the residential schools and the imprisonment of communities of Indigenous nations in colonial Canada.

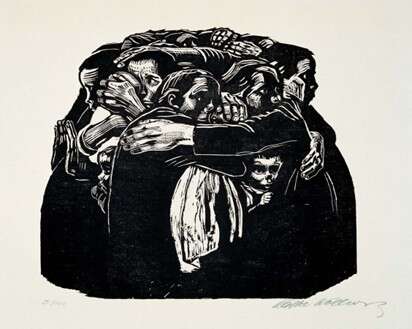

In her poem, Eng – like Davis in her book – highlights a particular phrase on G4S’s website: “in more ways than you might realize/G4S is securing your world” (Eng 84). In response to this phrase, Davis demonstrates how “G4S insinuated itself into our lives under the guise of security and the security states,” including “racist technologies of separation and apartheid” (55-56). G4S has produced business-like models and policies that sell a false narrative of individual security while simultaneously providing the neoliberal and carceral state with the technology and resources to profit off of the confinement and incarceration of peoples. The subject of Eng’s poem – Carole – feels and experiences this dehumanization deeply. When citing the inspiration for her poem, Eng states that “in reality [Carole] died of the system but in my dreams and in this poem she lives on” (102). Within this vigil held for a life lost to the carceral state, Eng’s poetry also resists the totalizing effect of globalization and privatization by calling on the historical practices and connections between generations and communities – the blanket. Eng’s poem defines Carole’s blanket as “G4S-resistant,” and that Carole is weaving this blanket to keep Indigenous children and future generations safe from the destruction of prison privatization and the systemic racism within G4S global policy. Carole’s G4S-resistant blanket is similar to the “Witness Blanket” which consists of “hundreds of objects from Canada’s residential schools” (CBC 2015). Both the G4S-resistant blanket and the “Witness Blanket” use historical memory to resist settler-colonial and neoliberal oppression. With this blanket, the weaving of collective experiences within the carceral state becomes the bonding material – both tangible and imaginary – to join communities and generations in a resistance to neoliberal logic and its politics of disposability.

As identified by Davis and Eng in their works, G4S’s globalizing influences go beyond the physical prison because it sells and propagates the best policies and technologies to both privatize and militarize educational systems and spaces. In Prison Industrial Complex Explodes, Eng outlines real cases and records of young Indigenous and BIPOC children held in either custody or “youth detention facilities.” For example, in 2003, Ashley Smith, “a 14-year-old Indigenous girl, was confined to a youth detention facility for 1 month after throwing crabapples at a postal employee. The initial 1-month sentence lasted almost 4 years, almost entirely in isolation, until her death by self-strangulation in 2007” in a Kitchener, Ontario facility (Eng 44). For Ashley Smith and many other youths, the school is now replaced with a detention center, teachers replaced with prison bars and prison guards, and community support replaced with a solitary confinement cell. As Angela Y. Davis defines in Freedom is a Constant Struggle, these dangerous and oppressive neoliberal efforts are all for profit and economic expansion: “education and incarceration have been linked under the sign of capitalist profit” (57). Youth detention facilities are replacing schools and educational spaces because of the complete minimizing of public funding as privatization and deregulation of the economy and political funding focuses on the expansion of prisons. “The financial costs alone of maintaining this prison culture are extravagant,” Giroux explains, “blowing a massive hole through tattered state budgets while undermining their most basic public services, including education and healthcare” (“Locked Up” 21). As youth detention centers increasingly operate as educational spaces, schools are also increasingly using carceral technology, security measures, and surveillance.

As a poetic form of resistance to these oppressive tactics, Eng vividly depicts her intimate interactions with both privatized security and surveillance within her poem: “first metal detector/first Halloween costume/a white onesie with drawn-on black stripes/father’s prison ID no. 5915 on baby breast” (80). Here, Eng associates important childhood milestones, like first Halloween costume, with more traumatic experiences like her costume of a prisoner resembling her father’s reality or being faced with a metal detector and being criminally surveyed as a young child. In a supportive society, a prison complex and early childhood experiences should never meet or coincide. In this current neoliberal society and politics, however, informative experiences for children are being informed not by open, pedagogical, and educational spaces but instead by the rules and confinement of the carceral state. Particularly for children in BIPOC or impoverished (i.e., neoliberally disposable) communities, “schools look like jails; schools use the same technologies of detection as jails and they sometimes use the same law enforcement officials” (Davis, Freedom is a Constant Struggle, 56). The prison system is increasingly becoming the operative brain of society, politics, and, most importantly, culture; this is the context in which Mercedes Eng is writing and compiling her poetic and creative works. Within her work, however, Eng’s resistance is in her specific placement of both Ashley Smith’s real case and with Eng’s “First Experiences” poem. By juxtaposing these two stories, Eng demonstrates the real impact and trauma behind either experiencing yourself, enduring second-hand, or watching young children grapple with the oppressive carceral state and its violent logics. Eng’s book demonstrates how neoliberal politics and privatization is impeding on educational/civic spaces and, as a result, children are becoming more desensitized to the violence they experience because now schools are jails, and jails are schools. There is no longer a separation between violent surveillance and an education with the freedom to learn, understand, and engage.

In Eng’s work, the physical walls or fences of the prison also become a familial meeting place. Eng continues to reflect and express her yearly visits with her father in jail, beginning with her first visit before she was born: “a tall tall fence […]/a strawberry-picking pass/a rumour about prison labour stoppage […] a pregnant 19-year-old white girl and new charges” (20). In a fractured narrative of remembered experiences, Eng exemplifies the carceral state’s overwhelming role in her formative years and in her familial connections and relationships. In their work Generations Through Prison: Experiences of Intergenerational Incarceration (2020), authors and interviewers Mark Halsey and Melissa de Vel-Palumbo share their findings after extensive interviews with various individuals and families who have intimate, generational interactions with the prison industrial complex; for example, they highlight the “normalizing function of various prison rituals (such as family visits and unintended ‘inculcation’ of children to prison climates) and their impact on the next generation” (4). Similar to how the carceral state replaces educational spaces and critical pedagogy, the prison industrial complex also informs and dictates familial conversations and relationships. In Eng’s poem, a “tall tall fence” is between her and her father and, since her birth, Eng’s relationship with her father has predominantly been dictated by the punishing state’s forced separation of important parental-child relationships.

In the same poem, Eng describes the various “roles” her father has played within the prison industrial complex; for example, her father is a man behind bars, a father separated from his young child, and a labourer for the carceral state. Similar to Eng’s use of the Ashley Smith case, Eng’s poetic-resistance is in her ability to compare and contrast these starkly different roles of her father – the one in her life and the one incarcerated. In her book, Eng shares a photo of her father at a labour station in British Columbia (73) and she compares these photos with family pictures of her mother, her father, and herself outside of the “tall tall fence” of the prison (18). Therefore, outside of the prison’s confining walls, Eng’s father is her father but, inside the prison’s walls or outside in the labour stations, Eng’s father is understood as a disposable labourer for the carceral state. As Davis states in Freedom is a Constant Struggle, human beings are viewed simply as for-profit-bodies in the privatized prison system: “it consists of the outsourcing of prison services to all kinds of private corporations, and these corporations want larger prison populations. They want more bodies. They want more profits” (24). Underneath for-profit neoliberal privatization, there is both physical and symbolic violence ingrained within the prison industrial complex.

Giroux defines how there is a type of “symbolic violence” at work in various neoliberal apparatuses; this symbolic violence is particularly marked by the misuse and abuse of language where certain words or terms no longer signify certain meanings or values, and where language borders on meaningless (Pandemic Pedagogy, 30). Eng demonstrates this symbolic violence against language when she expresses the prison industry’s conflation and gross misrepresentation of two words – “prison” and “labour”: “a strawberry-picking pass/a rumour about prison labour stoppage” (20). In a neoliberal and privatized society, prisoners are criminalized in order to perform practically free labour, and provide industry and products for the corporations that are cementing their incarceration. Immediately after her poem, Eng cites an announcement from “Correctional Service Canada” in 1981 where the pay for labourer prisoners was “$3 a day,” and, in response to a prisoner strike against this dehumanization, a “spokesperson for the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness called the strike ‘offensive to hard-working law-abiding Canadians’” (Eng 23). There is great violence in the language of this announcement as prisoners are separated from “actual” citizens of Canada and are therefore situated in a violent zone of disposability.

Beyond this symbolic violence, Eng endures and experiences first-hand the physical violence administered by the carceral state. In the same poem, Eng cites her father’s escape from prison, and reflects on her family’s drive from the prison outside of Vancouver to their home in Medicine Hat:

The car stops suddenly and

then there are two really angry men yelling, “open the

fucking door!” they smash open the window, and they’re

both grabbing my dad, one by the hair, the other by the

throat. It looks like they wanna strangle him. My dad is

kicking, he’s fighting. But it doesn’t work, they take him

and he’s gone. (Eng 19)

In this memory, Eng is two years old. While her father endures the physical violence, Eng herself endures the pain of witness trauma. Along with the trauma of this experience, Eng is also forced to – at the young age of two years old – reckon with the reality of neoliberal violence. In Race, Politics, and Pandemic Pedagogy, Giroux defines this neoliberal violence as such:

In the neoliberal worldview, those who are unemployed, poor consumers, or outside of the reach of a market in search of insatiable profits are considered disposable. Increasingly viewed as anti-human, unknowable, faceless, and symbols of fear and pathology. This includes […] those who are considered of no value to a market society, and thus eligible to be deprived of the most basic rights and subject to the terrors of state violence. (77-78)

As Eng grapples with witnessing her father’s pain, she also must grabble with the zone of disposability she has now been placed in, along with her father and her family. For Eng, this is the legacy and history of the prison industrial complex. Beyond the bars and fences of the prison building, neoliberal violence and surveillance continues to stalk and confine her. As defined in the title of her book Prison Industrial Complex Explodes, Eng, like Davis and many others, does not want criminal justice reform or corporate reconfiguration; instead, Eng wants the entire system to implode and for her readers to, as Davis defines, see beyond the bars and to recognize the current and intergenerational pain and suffering produced and manufactured by the prison industrial complex.

Throughout Prison Industrial Complex Explodes, Mercedes Eng demonstrates individual trauma and societal/cultural trauma produced by the prison industrial complex and the carceral state’s increasing violence, surveillance, and dehumanization. In depicting generational experiences with mass-incarceration, Eng attempts to demonstrate both the childhood stolen and commodified and the familial structure replaced by metal detectors in schools and visits through prison bars and tall fences. Furthermore, in her poetic-resistance technique of compare and contrast, Eng works to separate the conflation of the carceral state with educational spaces, to de-normalize private security’s power over civic culture, and to defamiliarize the replacement of familial and communal structures with prison systems. Essentially, Mercedes Eng’s creative work – and the works of many others – can stand resistant to neoliberal normalization. As Davis defines in her work Freedom is a Constant Struggle, in a neoliberal society, “prisons are constituted as ‘normal’” and so “we have to learn how to think and act and struggle against that which is ideologically constituted as “normal” (100). Demonstrating the cultural and social significance of the abolitionist movement, Davis continues to state that “it takes a lot of work to persuade people to think beyond the bars, and to be able to imagine a world without prisons and to struggle for the abolition of imprisonment as the dominant mode of punishment” (100). Along with the critical pedagogical works of Angela Y. Davis and the creative works like Mercedes Eng’s Prison Industrial Complex Explodes, we can begin to reframe beyond neoliberal domination and reclaim a collective existence founded in critical engagement, human connection, and substantive rights and freedoms.

Works Cited

Camp, Jordan T. Incarcerating the Crisis: Freedom Struggles and the Rise of the Neoliberal State. University of California Press, 2016.

Cecco, Leyland. “‘National travesty’: report shows one third of Canada’s prisoners are Indigenous.” The Guardian, 22 Jan. 2020, theguardian.com/world/2020/jan/22/one-third canada-prisonersindigenous-report. Accessed 29 Mar. 2021.

Davis, Angela Y. Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement, edited by Frank Barat, Haymarket Books, 2016.

—. “Masked Racism: Reflection on the Prison Industrial Complex (1998).” JIE: The Justice-In Education Initiative at Columbia University, http://justiceineducation.columbia.edu/curriculum/resources/masked-racism-reflections onthe-prison-industrial-complex/. Accessed 30 Mar. 2021.

Eng, Mercedes. Prison Industrial Complex Explodes: A Poem. Talonbooks, 2017.

Giroux, Henry A. Interview by Julian Casablancas. Rolling Stones, 13 Sept. 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hLRWPsIzSOo. Accessed 7 Apr. 2021.

—. “Locked Up: The Youth Crime Complex and Education in America.” JAC, vol. 30, no. 1/2, 2010, pp. 11-52.

—. Race, Politics, and Pandemic Pedagogy. Bloomsbury, 2021.

Halsey, Mark, and Melissa de Vel-Palumbo. Generations Through Prison: Experiences of Intergenerational Incarceration. Routledge, 2020.

Harris, Kathleen. “COVID-19 hit federal prisons twice as hard in 2nd wave of pandemic, report says.” CBC, 23 Feb. 2021, https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/csc-prisoners-covid19second-wave 1.5923707. Accessed 29 Mar. 2021.

Price, Byron Eugene, and John Charles Morris. Prison Privatization: The Many Facets of a Controversial Industry. Praeger, 2012.

Rich, Adrienne. “Arts of the Possible.” Essential Essays: Culture, Politics, and the Art of Poetry, edited by Sandra M. Gilbert, W.W. Norton, 2018, pp. 326-344.

“Witness Blanket weaves residential school memories together.” CBC, 14 Dec. 2015, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/witness-blanket-cmhr-winnipeg-1.3363889. Accessed 1 Apr. 2021.

Read more at By Emma Wood.

Essays, ResistanceRelated News

News Listing

By Rosemary Kasiobi Nwadike ➚

Feminist Miseducation in the Afro-West: Examining (In)Formal Gender Indoctrinations

Articles, Education, Resistance, Social Justice

July 11, 2025

By Alexis Andrade ➚

Radical Love: A Revolutionary Force for Liberation

Articles, Cultural Pedagogy, Resistance

June 26, 2025

By Rosemary Nwankasiobi Nwadike ➚

Systemic Marginalization: The Criminalization and Militarization of Nigerian Youths

Articles, Democracy, Resistance, Social Justice

May 6, 2025