The Village of Islington Murals: Exploring the Role of AR and the Artist in Resisting Neoliberal Fascism in Public Art

Graffiti and murals have a critical pedagogical function with the potential to visually transform urban space into sites of political, cultural and social resistance. From Diego Rivera to Banksy and beyond, artists have claimed underused surfaces of concrete and brick as a canvas to raise consciousness, share knowledge, and critically examine hegemonic systems of power. Despite this subversive potential, murals have become increasingly neoliberalized, used as a visual tool by both the private and public sector to define neighbourhood identity, to normalize dominant histories, and to spur gentrification projects. In the City of Toronto, programs such as StART (Street Art Toronto) have been established to oversee the strategic development of a city-wide mural program, financially supporting over 350 mural installations across the city in 2022 alone. (City of Toronto, 2023). In How Fascism Works, Jason Stanley writes that “in fascist ideology, the products of intellectual life that it supports – culture, civilization and art – are solely productions of members of the chosen nation.” (Stanley, 2018, p.49). The ongoing proliferation of murals through municipal and state funded programs ultimately aims to render their cultural production as visual static, to be seen but not considered–the colourful background to capitalist beautification and revitalization projects.

This process of production shifts mural creation from bottom-up, groundswell action to top-down, state driven initiatives, directing focus on the dominant narratives while being dismissive of the broader community members. But how can artists and community members resist neoliberal and fascist agendas, and reclaim public space as a site of critical pedagogy and discourse? In this paper, I will examine the efficacy of Augmented Reality (AR) to provide counter narratives for public mural projects. What are the strengths and what are the limitations? Can AR support artists and community members effectively in calling attention to neoliberal and fascist systems of power? To frame this analysis, I will look specifically at one project, the “Augmented Reality in the Village of Islington” project led by Local Art Service Organization Arts Etobicoke, whose goal was “to diversify the artistic narrative of our community to more accurately reflect the citizens who live and work in The Village of Islington.” (Arts Etobicoke, 2023). I will argue that despite the use of AR to create a counternarrative, the Murals of Islington project is a pedagogical tool for propaganda, upholding neoliberal capitalism while reinforcing and normalizing white supremacist ideologies of the mythic past. It is imperative that the artists involved in municipal mural programs realize their role and responsibility as ‘border intellectuals’ (Giroux, 1995) in order to disrupt and transform public artworks into critical pedagogical sites. To begin, I will provide a brief literature review which grounds my analysis in current scholarly discourse around the neoliberalization of public art, the role of the artist, and the function of AR in creating counter narratives. The body of my paper is divided into three sections: Village of Islington Murals and its role perpetuating neoliberal and fascist systems of oppression, the Arts Etobicoke AR project, and the role and responsibilities of the public artist.

Literature Review

Public art and murals have the power to define a community, foster a sense of belonging, and visually represent local culture, ideals, histories, beliefs, and radical futures. Artists play an integral role in facilitating these outcomes (Enright & McIntyre, 2019; Thomas et al, 2015; Toolis, 2017). Nonprofits, municipalities and Business Improvement Areas (BIAs) have increasingly recognized the value and opportunity that public art and public artists present, and have developed cultural strategies, policies and programs that position artists and creative industries as key economic drivers (Friedmann, 2010; Florida, 2002; Levin & Solga, 2009; Molnár, 2017; Scott, 2006). In Toronto, mural programs through StreetART Toronto, ArtworxTO and the Toronto Association of Business Improvement Areas (TABIA) offer funding to artists and BIA’s to facilitate local mural projects and implement the City of Toronto’s vision to “empower creativity and community, everywhere.” (City of Toronto, 2019). On paper, these initiatives sound both innovative and promising, supporting a diverse roster of emerging and established artists to transform underused urban spaces into vibrant works of art that represent local community priorities. But in reality, the proliferation of murals installed across the city diminishes the subversive and transgressive political power that murals are capable of holding, limits the creative freedom of artists as cultural producers by directly tying the mural production to municipal beautification initiatives, and aligns public art with capitalist, and at times, fascist ideologies.

As murals visually relay local histories and narratives, they are often used as forms of erasure, framing only the stories and experiences of dominant social groups while excluding oppressed and marginalized voices and daily lived experiences (Chapple et al, 2010, McLean, 2018). Historical murals in particular often focus on imagery of the mythic past, relying on nostalgia, systemic hierarchy, and a lack of critical awareness referred to by Stanley as anti-intellectualism which “sends signals as to who belongs and may even serve to normalize and make social differences and inequalities more visible.” (Grodach, 2009, p.477). In normalizing systems of power, white supremacy, and neoliberal ideologies by presenting a single history as the truth, murals become a pedagogical tool of propaganda for the dominant class and state working as “a mechanism to achieve power” (Stanley, 2018, p.xiv) across borders of social and cultural production. How then can artists and community members respond and resist neoliberal fascist enclosure of public space through public art? New technologies such as AR have been touted as a way to interject and overlay critical anti-colonial and anti-racist pedagogy and counter narratives onto permanent public art works. AR provides artists the ability to directly transform 2D surfaces into 3D immersive experiences, introducing responsive audio and visual components while blurring the lines between physical and virtual worlds (Park and Seo, 2020; Dolinsky, 2022).

While it has been argued that AR enriches and is able to articulate counter narratives that subvert dominant systems and discourses (Yepez-Reyes et al, 2023), AR technology is reliant on an individual’s ability to access and effectively navigate the technology and remains liminal and limiting of social change, “offering a one-way discourse” to those aware of its existence. (Crary, 2022, p.120). While, “no single view of public space and the art that occupies it will work in a metropolis of multiple perspectives,” (Baca, 2019, p.306), the public artist must extend past being a mere producer of visual and cultural imaginary in order to play a pivotal role as a “border intellectual,” defined by Henry Giroux as cultural workers who “function in the space between “high” and popular culture; between the institution and the street; between the public and the private.” (Giroux, 1995, p. 5). Choices that are made must be critical, create space for community discourse and response, understand that “consciousness leads to action,” and actively subvert and resist fascist neoliberal systems that attempt to control and direct their work (Giroux, 1994, Giroux, 2023; Becker, 1994; Becker, 1995). In the following section, I will introduce and examine the Village of Islington Murals as tools of fascist neoliberalism that act as modes of erasure and pedagogical propaganda, using education as “a tool for domination” (Giroux, 2023), perpetuating the mythic past and reinforcing systemic hierarchies.

The Village of Islington Murals

The Village of Islington surrounds the intersection of Dundas Street West and Islington Avenue in Toronto’s west end and is branded as “Toronto’s village of murals.” (Village of Islington BIA, 2020). With over 25 large scale permanent murals in the official collection, the majority have been painted by local artist John Kuna since 2004. Since that time, the project has won multiple awards and gained media attention both locally and nationally, and has been financially supported by the City of Toronto. As a mode of creative placemaking, The Village of Islington BIA (Business Improvement Association), whose mandate is to “beautify and promote the dynamic Islington business area,” (Village of Islington BIA, 2020), has leveraged these works to attract visitors to their neighbourhood and drive business to local shops. Claimed as “a celebrated treasure of Toronto’s west end…the murals attract great interest in their depiction of the life and times in the old village of the 1800s and early 1900s.” (TABIA, 2023). The mural project has become so central to the BIA’s identity and the identity of the branded community that their website not only details each of the 28 mural projects, it features a map, an art walking tour, and a distorted timeline that aligns the history of the area to the dates represented in the murals. According to Kuna and the BIA, if it weren’t for the productive and pioneering nature of white settler colonists, the area would not be what it is today.

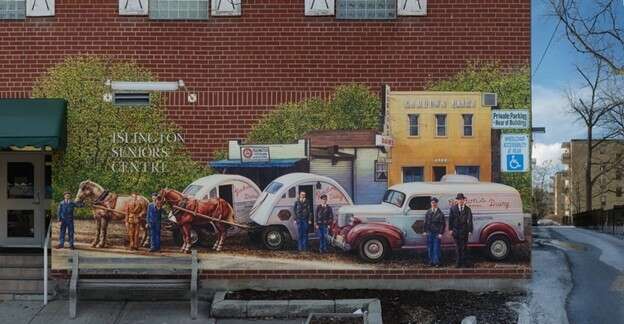

This message is clearly conveyed throughout the murals produced by Kuna, ignoring the role of Indigenous nations that governed and cared for the land before 1808, as well as the countless number of Black, immigrant and refugee populations that have called the Islington and Dundas area of Toronto their home. To Kuna and the BIA, their histories, communities and contributions did not exist. Stanley writes that fascism is able to render and maintain ideas of the other through an interconnected network of strategies including the mythic past, propaganda, anti-intellectualism and hierarchy. (Stanley, 2018). Each of those elements are directly used as visual catalysts to unify and maintain a dominant and one-sided historical narrative while producing a “manufactured ignorance.” (Giroux, 2023). Throughout the works, which span five city blocks, the unifying theme of the mythic past is overwhelming in Kuna’s work. Batterby’s March (Fig.1) depicts a moment in white settler colonialism which “affirm[ed] Canada’s ties with Britain and ensur[ed]that Canada could develop as a unique, independent nation.” (Village of Islington BIA). This image of settler colonial exceptionalism strategically positions visually the “hierarchical construction of history to displace truth, and the invention of a glorious past [which] included the erasure of inconvenient realities.” (Stanley, 2018, p.15). This glorious past is further perpetuated in The Manse Committee (Fig. 2) which features the interior perspective of a privileged Victorian household, or Gordon’s Dairy (Fig. 3), which centres and prioritises entrepreneurship, productivity and leisure. Void from these depictions are any consideration of race, class and ability. White heteronormative ability is highlighted as the foundation and pathway to economic, social and cultural prosperity as well as nation-building.

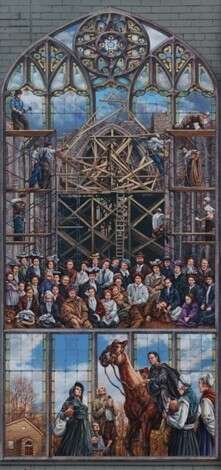

Hierarchies and white supremacy are further reinforced through murals that centre the work of the church and Christian morality. Faith of Our Fathers II (Fig. 4) features the building of the Islington United Church, originally the Wesleyan United, highlighting and celebrating not only the labour, skills and dedication of the stone masons, but also the selfless acts of the ministers who rode to neighbouring villages spreading spiritual word. In this image, there is no attempt to critically examine, draw attention to, or critique the role of the church in the ongoing genocide of Canada’s Indigenous people. Once again, celebrated in this work is the white saviour, who is responsible for our modern day social and economic prosperity. The works show a shallow, one-dimensional vision of Canada’s historic past and neatly fit into white supremacist neoliberal and fascist systems of dominance while dismissing, othering and erasing more complex and accurate readings of history. In an interview from 2021, Kuna states, “through the work, one acquires a perspective into how a city changes over time, how it transforms in terms of geography, demographics and identity. That’s really the importance of a project like the Islington murals. It has didactic value.” (AGO, 2022). As didactics, these murals act as tools of pedagogical propaganda, visually rendering “the language of virtuous ideals to unite people behind otherwise objectionable ends.” (Stanley, 2018, p.24). Furthering the neoliberal ideals of both the BIA and state mural programs, the murals directly and implicitly centre the individual, the entrepreneur who pulls up his bootstraps and lays a foundation for economic prosperity. These murals brand the neighbourhood, visually identifying which community members matter. As they are nowhere near representative of the real community that supports them, what can be done to actively disrupt and critically transform these narratives?

Augmented Reality as Counter-Narrative

In 2020, in an attempt to draw attention to the racist retelling of history provided in these murals, Local Art Service Organization (LASO) Arts Etobicoke worked with a collective of 11 BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and Person of Colour) professional and community-based artists to developed a series of Augmented Reality (AR) counternarratives that digitally overlaid the murals. Art Etobicoke, which is one of 6 LASOs working at arms-length from the City of Toronto has been in operation for 50 years and is located in the heart of The Islington Village Mural project. (Arts Etobicoke, 2023). They serve a diverse population of youth, adults and seniors, many of whom are newcomers, refugees or new Canadians, offering free interdisciplinary arts programming, a local gallery, and coordinated arts advocacy. The Augmented Reality of the Village of Islington is the second AR project undertaken by Arts Etobicoke and was launched in 2020 as part of the City of Toronto’s Year of Public Art. The project’s “activations are designed to reflect the people who live and work today in The Village, and to share stories from the community with a focus on immigration and Indigenous voices.” (Shephard, 2021). To further engage community members and those interested in a more complex and critical dialogue around the morals, a series of arts workshops were also hosted at Art Etobicoke over the 2021-22 year. Arts Etobicoke further developed a map and hosted walking tours featuring an “Indigenous Knowledge Keeper and Storyteller, local Etobicoke Historians, [and] an Afro-Caribbean Performance artist.” (ArtworxTO, 2022). As a means of introducing alternate readings of the mural works, the AR project aimed to use technology as a means of centring knowledge and histories of BIPOC voices.

Philip Cote, an artist, historian, wisdom keeper and member of Moose Deer Point First Nation provided Indigenous, anti-colonial counter-narratives for two of the mural works featured in the Augmented Reality of the Village of Islington project, including Batterby’s March (Fig 1). As an introduction to his analysis he states: “The history of this country Canada rests on a single settler narrative and lens that marginalizes Indigenous contributions since the earliest documentations of European arrival and it is at this point we begin to see the importance of why Indigenous people were vanished from written colonial histories and narratives.” (ArtworxTO, 2022). The Village of Islington Murals directly reinforce and re-enact systemic violence and oppression of our Indigenous peoples, co-opting public space as a platform to reinforce and promote white settler colonialism as the saviour of our nation and foundation of individual economic prosperity. Stanley writes that people “suffer from a sort of amnesia of wrongdoing when the perpetrators are characterized explicitly as their countrymen.” (Stanley, 2018, p.20). Through AR technology, the Augmented Reality of the Village of Islington project draws attention to the fascist and neoliberal ideologies that support these works, transforming the murals from locations of pedagogical propaganda of the nation state to sites of critical pedagogical disruption. “AR is one of the technologies that can boost the circulation of future discourse” (Yepez-Reyes et al., 2023, p.400), but as the technology relies on individuals to access the content through their phones or digital devices, can the project be a successful means of social justice and critical resistance?

While this project is an important step in subverting and resisting blatant neoliberal and fascist cultural production found in the Village of Islington Murals, the artwork and oral histories shared through this important project are limited in scale, impact and accessibility. Perhaps due to funding or timeline constraints, the Augmented Reality of the Village of Islington project created AR works for 8 of the 28 murals, and of the 8 responses, only three were led by BIPOC artists and/ or community members. As funding for the project was provided primarily through the City of Toronto, with 5 of the 7 funders being programs within the city or funded through the city (Arts Etobicoke, 2023), one must ask how subversive the project could actually be. What were the limitations placed on the project by the state? While the project was promoted through Art Etobicoke, their LASO partners, and the City of Toronto, if one was not aware of the project and how to access the information digitally, one would never know an important counter narrative existed. As a result, the project veers towards an act of performative activism, checking boxes for the state funders who wish to increase perceptions of equity, diversity and inclusion in their work.

The reliance on personal digital devices such as phones or tablets create accessibility issues, assumes that everyone has access to expensive pieces of equipment, and relies entirely on the individual’s ability in navigating the applications needed to view the AR works. In centring the individual over the collective, the project limits its pedagogical function, reproducing “solitary subjectivities…deter[ing] cooperative forms of association, and… dissolv[ing] possibilities for reciprocity and collective responsibility” (Crary, 2022, p.123). The focus on the individual ultimately reinforces ongoing acts of erasure that are experienced by BIPOC communities through neoliberal, capitalist ideologies. While “Introducing AR to a mural is a form of hijacking art…it does not replace the art since its presence is compulsory and acknowledged.” (Yepez-Reyes et. al., 2023, p.407). In other words, AR is and can only be an ephemeral veil, and the original artwork maintains its permanence and pedagogical power. Additionally, as technology and digital platforms continue to change and develop, the project and the important counter narratives provided by Black, Indigenous and racialized artists are once again at risk of being lost and erased from public knowledge while allowing the dominant narrative celebrated within the Village of Islington mural series to remain.

The Role and Responsibility of the Pubic Artist

While technology like AR can provide artists, educators and activists a tool to combat, resist, and subvert dominant hegemonic narratives that serve only neoliberal and fascist systems of power, they are unable to raise critical and collective consciousness that can move the dial of social justice forward. What then is the role and responsibility of the public artist? In Critical Pedagogy in the Age of Fascist Politics, Henry Giroux argues that education, specifically critical pedagogy as a project, is imperative in resisting and countering fascist politics and neoliberal ideologies. (Giroux, 2023). Considering the role of the artist as a border intellectual residing between institution and public space, existing both within and outside of hegemonic systems of power, it is imperative that the public artist acknowledge and accept the responsibility of a critical public educator, striving to subvert and counter oppressive, racist and systemic inequities. Public artists must begin to move away from the neoliberal framework established by the public and private sector where their work is only there to beautify and gentrify, recapturing the essence of street art and graffiti culture which used the public space as a means to disrupt the visual static of capitalist urbanism. As we have seen in the Village of Islington Murals, the artist holds a great deal of power in both interpreting and rendering how a ‘community’ is represented visually. The murals produced by Kuna present murals as anti-intellectual commodities, uncritically upholding and reproducing neoliberal and fascist ideologies while erasing lived histories and experiences of the “other.”

Additionally, The Village of Islington Murals are an example of curated censorship, refusing and erasing the voice, knowledge and history of oppressed and marginalized groups. In her introduction to The Subversive Imagination, Carol Becker writes, “censorship of the arts present a failure of democratic institutions to articulate and defend the complexity and diversity of the American citizen.” (Becker, 1994, p. xii). To refute and resist, artists must re-examine not only how they use their tools of visual language, they must reconsider their agency as cultural producers and actively position themselves as critical education facilitators in order to untangle their work from neoliberal and fascist systems of power. This work cannot be done alone. Artists as border intellectuals and creative labourers must approach the reimagining of public art as a collective action, embedding subversive and critical discourse through their work in the public sphere. Here I draw on Becker once more and her idea of forming a national organization of artists who collectively support and advocate for their rights, resisting neoliberal and fascist systems of oppression (Becker, 1995), systems which ultimately limit and even criminalize the radical and pedagogical act of visually disrupting public space with art. While technology can assist in disseminating critical knowledge to the masses, it cannot permanently disrupt the visual rhetoric of neoliberal ideologies. That can only be done by the artists themselves, and as a collective act of resistance.

Conclusion

In introducing the Village of Islington Murals, the AR counter-narrative and the role and responsibility of the artist, it was my attempt to call attention to the ever-increasing neoliberalization of public art and the imperative importance of the artist moving out of contract cultural producer to critical border intellectual. With the proliferation of murals in our urban landscape that exists only to beautify, brand, and define dominant community identities, public art has become wallpaper, easily ignored, or accepted. As a mode of visual knowledge generation and public pedagogy, it is imperative that we as a society begin to pay attention to the murals in our neighbourhood, question their intent and consider the narratives they provide critically. The Augmented Realities of the Village of Islington project shows first-hand the difficulties faced when working to subvert fascist framings of history, constraints of project scale, accessibility, cost and funding, potential changes to technology and the reliance on individual over collective action. While AR has been seen as a potential tool that can help amplify counter narratives and spur critical consciousness, it has limitations and could end up serving neoliberal ideologies.

“In fascist ideology, the products of intellectual life that it supports – culture, civilization and art – are solely productions of members of the chosen nation.” (Stanley, 2018, p.49). It would be naive to assume, as suggested in my writing on the role and responsibility of the artist, that if artists only worked together, they could resist an increasingly fascist and neoliberal system that thrives off their labour. Quite the opposite, for each left-leaning, anti-oppressive artist striving to take on complex public projects, there is an uncritical artist waiting to get paid in the wings. In this tension lies the need for further scholarly research, focused on the artist’s role as public intellectual and the critical untangling of neoliberal cultural networks that restricts collective action and resistance by artists in public space.

Fig. 1. John Kuna, 2012, Battersby’s March. https://www.villageofislington.com/mural-map/

Fig. 2. John Kuna, 2010, The Manse Committee. https://www.villageofislington.com/mural-map/

Fig. 3. John Kuna, 2008, Gordon’s Dairy. https://www.villageofislington.com/mural-map/

Fig. 4. John Kuna, 2009, Faith of Our Fathers II.https://www.villageofislington.com/mural-map/

Works Cited

Arts Etobicoke. (2023). Augmented Reality in the Village of Islington Murals.

AGO (Art Gallery of Ontario). (2021). Painting a Public Archive. Retrieved from,

https://ago.ca/agoinsider/painting-public-archive

ArtworxTO. (2022). Village of Islington Murals curated by Arts Etobicoke. Retrieved from,

https://www.artworxto.ca/tour/village-of-islington-murals

Baca, J.F. (2019). Whose Monument Where? Public Art in a Many-Cultured Society. In Jennifer A. González, C. Ondine Chavoya, Chon Noriega, Terezita Romo (eds). Chicano and Chicana Art, A Critical Anthology, (pp.304-309). Duke University Press. (Original work published in 1995).

Becker, C. (1995). Survival of the Artist in the New Political Climate. In Carol Becker and Ann Wiens (eds.), The Artist in Society: Rights, Roles, and Responsibilities, (pp.56-64), New Art Examiner Press.

Becker, C. (1994), Introduction, Presenting the Problem. In Carol Becker (eds.), The Subversive Imagination. Artists, Society & Social Responsibility, (pp. xi-xx). Routledge.

Chapple, K., & Jackson, S. (2010). Commentary: Arts, Neighborhoods, and Social Practices: Towards an Integrated Epistemology of Community Arts. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 29(4), 478–490.

City of Toronto. (2023). City of Toronto Celebrates Success of ArtworxTO: Toronto’s Year of Public Art. Retrieved from, https://www.toronto.ca/news/city-of-toronto-celebrates-success-of-artworxto-torontos-year-of-public-art/

City of Toronto. (2019). Public Art Strategy. Retrieved from, https://www.toronto.ca/explore-enjoy/history-art-culture/public-art/public-art-strategy/

Crary, J. (2022). Scorched Earth, Beyond the Digital Age toa Post-Capitalist World. Verso.

Dolinsky, M. (2022). Shifting Perceptions—Shifting Realities—Shifting Spheres. In Vladimir Geroimenko (ed.), Augmented Reality Art, From the Emerging Technology to a Novel Creative Medium. (3rd edition, pp.61-73). Springer.

Enright, T. E., & McIntyre, C. (2019). Art and Neighbourhood Change Beyond the City Centre. Canadian Journal of Urban Research, 28(1), 34-49.

Florida, Richard L. (2002). The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life. New York, NY, Basic Books.

Friedmann, J. (2010). Place and Place-Making in Cities: A Global Perspective. Planning Theory & Practice, 11(2), 149-165.

Giroux, H. (1995). Borderline Artists, Cultural Workers, and the Crisis of Democracy. In Carol Becker and Ann Wiens (eds.), The Artist in Society: Rights, Roles, and Responsibilities, (pp.4-14), New Art Examiner Press.

Giroux, H. (2023). Critical Pedagogy in the Age of Fascist Politics. Counterpunch.

Grodach, C. (2010) Art Spaces, Public Space, and the Link to Community Development. Community Development Journal, 45(4), 474–493.

Levin, L., & Solga, K. (2009). Building Utopia: Performance and the Fantasy of Urban Renewal in Contemporary Toronto. TDR: Drama Review, 53(3), 37-53.

Molnár, V. (2017). Street Art and the Changing Urban Public Sphere. Public Culture, 29(2), 385-414.

Park, H., & Seo, Gapyual, S. (2020). Towards the User Interface of Augmented Reality-Based Public Art. IN XX (eds.), In Constantine Stephanidis and Margherita Antona (eds.), HCI International 2020 Posters, 22nd International Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark. (pp. 317-335), Springer.

Scott, A. J. (2006). Creative Cities: Conceptual Issues and Policy Questions. Journal of Urban

Affairs, 28(1), 1-17.

Shephard, T. (2021). Arts Etobicoke leads guided tours of augmented reality Village of Islington Murals. Retreived from, https://www.toronto.com/things-to-do/arts-etobicoke-leads-guided-tours-of-augmented-reality-village-of-islington-murals/article_e7a612cd-cd82-592d-a1f7-ee11a6344a22.html

Stanley, J. (2018). How Fascism Works, The Politics of Us and Them. Random House, New York.

TABIA (Toronto Association of Business Improvement Associations). (2023). Welcome to Village of Islington! Retrieved from, https://www.toronto-bia.com/find-a-bia/bias/village-of-islington/

Thomas, E., Pate, S., & Ranson, A. (2015). The Crosstown Initiative: Art, Community, and Placemaking in Memphis. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55(1-2), 74-88.

Toolis, E. E. (2017). Theorizing Critical Placemaking as a Tool for Reclaiming Public Space. American Journal of Community Psychology, 59(1-2), 184-199.

Village of Islington BIA. (2020). Murals. Retrieved from, Mural Map – Village of Islington Business Improvement Area

Yepez-Reyes, V., Cevallos, P., & Córdova D. (2023). Hijacking Art: Murals as an Interface

Toward Augmented Reality. In López-López, P.C., Barredo, D., Torres-Toukoumidis, A., DeSantis A., Avilés O. (Eds.) Communication and Applied Technologies, Proceedings of ICOMTA 2022, (pp. 399-408), Springer Pub.

Read more at By Bebhinn Jennings.

Articles, Public Pedagogy, Social JusticeRelated News

News Listing

By Maya Phillips ➚

Failure to Reeducate: Perpetuations of Cultural Fascism in Post-War Germany

Articles, Cultural Pedagogy, Public Pedagogy

February 9, 2026

By Rosemary Kasiobi Nwadike ➚

Feminist Miseducation in the Afro-West: Examining (In)Formal Gender Indoctrinations

Articles, Education, Resistance, Social Justice

July 11, 2025