Countering Loneliness: The Application of Theater-Based Videogames in Reducing the Loneliness Caused by Videogame Addiction

Introduction

Considering the scale of social isolation in today’s societies, many are now arguing that we have entered the “age of loneliness” (Monbiot; Nilsson et al. 93). However, as critiques have rightly observed, it would be wrong to consider loneliness as a mere side effect of living in a modern society (Cotton 6; Monbiot). Rather, data shows that loneliness is, in fact, a perfect fuel for the engine of neoliberalism, which benefits greatly from humans’ social isolation. In a short 2014 blog article, the British author George Monbiot argues that a small group of the financial elite have made a fortune in the past decade by instilling a “life-denying ideology which enforces and celebrates our social isolation.” This “Hobbesian” state of the war “of every man against every man” (Hobbes 178), Monbiot argues, is the “religion of our time.”

While in the post-Covid19 era, the Internet seems to have taken the place of TV as a mainstream cultural resource, it seems to continue in the manner of TV in pushing humanity toward the “post-social society” against which Monbiot warns, a society in which competition over financial growth controls human behavior. One area where this is particularly evident is in the game play of the widely popular online videogames, such as Call of Duty Mobile, that praise a last-man-standing worldview according to which gaining more power as an individual is necessary for survival. Given that psychological data have proven a positive triangular relationship among loneliness, lack of interpersonal competence, and online game addiction (Lee et al. 386-391), the role of such videogames in propagating the aforementioned “life-denying” worldview by constantly calling the lonely players into such an ideology is undeniably grave. In response to this threat, this paper emphasizes the importance of developing videogames that help their users engage in community-based activities, rather than constantly trying to be superior to others in a hyper-individualist endeavor.

As a practical alternative, I claim that videogames inspired by the community-building power of theater can effectively increase their users’ interpersonal competence by engaging them in the social process of virtual theater making. Psychologists Brennan McDonald et al. have recently argued for the efficacy of theater-based interventions as means of reducing social isolation (3-6). In the same light, I will introduce theater-based videogames as powerful theater-based interventions, using the example of a videogame designed in 2015 by Gina Bloom et al. at the University of California, Davis. Thanks to their ludic nature, early modern plays could employ the power of interweaving plays and games to achieve maximal audience engagement (Bloom, Gaming the Stage 232-239). Accordingly, Bloom and her team have taken advantage of this feature in designing a mimetic-interface game called Play the Knave that allows users to engage safely in the social process of virtual theater making through playing out Shakespearean play texts[1]. Bloom et al.’s successful experience of using Play the Knave as a prototype of theater-based virtual reality game in the contexts of the 2015 Stratford Festival in Ontario (Gaming the Stage 235) and the elementary schools of South Africa (“Play to Learn”) is proof that such videogames can effectively increase their users’ interpersonal as well as intrapersonal competence, thus effectively reducing the level of loneliness among them.

Videogames and Loneliness

Emerging as an unsettling byproduct of the Anthropocene, loneliness has garnered significant attention in scholarly circles over the past few decades, with researchers examining its impact on human societies from various perspectives[2]. What unifies much of this scholarship, however, is a shared urgency to raise awareness of its severe consequences and to advocate for immediate action to curb its rapid proliferation in the 21st century.

Roughly defining loneliness as the want for “interpersonal intimacy” (Fromm-Reichmann 308), psychologists and public intellectuals have observed it as an integral factor in causing nearly any mental illness (Shulevitz). What has recently come to light, however, is that loneliness does not merely make life miserable, it also puts humans’ bodies in serious physical danger (DeVega). In the aftermath of the pandemic of AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s, a study performed by Steve Cole showed that the HIV-positive gay men who had remained “in the closet” were prone to a quicker death. A few years later, John Cacioppo proved that loneliness not only increased the probability of death in already sick people but also put healthy people in danger of becoming sick. Today, studies have shown that “Alzheimer’s, obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, neurodegenerative diseases, and even cancer,” are only part of the physical diseases that loneliness can either bring about or worsen (Shulevitz).

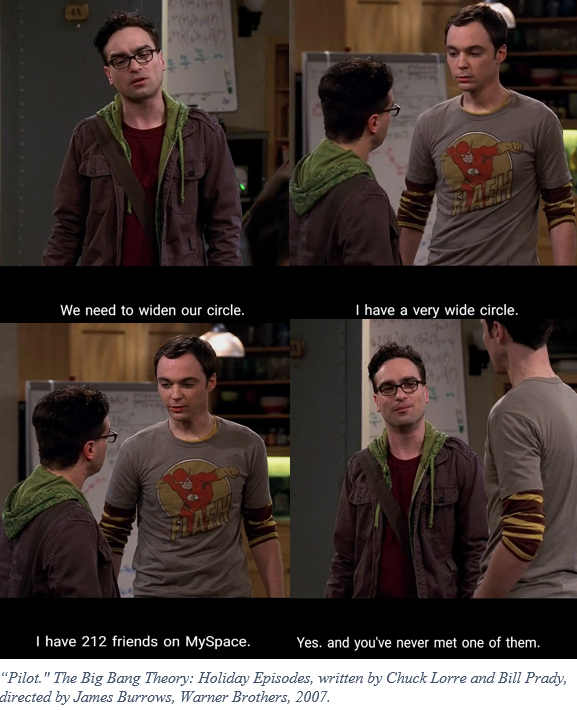

While it is highly disturbing that loneliness has only just recently become recognized as a mental condition worthy of scientific attention (Shulevitz), what is even more shocking is the speed with which it is spreading all over the world in an age when people are supposedly more connected to each other than any other time in human history. To find a better explanation for this lack of connection among “the most social creatures” (Monbiot), as Jess Cotton suggests, it would be beneficial to “[focus] on the structural forces in which loneliness arises,” as doing so “offers a useful way into a historical and political analysis that cuts through the social panic that surrounds the perceived ‘crisis of loneliness.’” To Cotton, loneliness is a “psychopolitical state” that is closely tied to “technological forms, social structures, cultural resources, and political movements” (6). Given loneliness’s direct connection to the problem of social isolation, gravely exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic (WHO “Advocacy Brief”), exploring the “technological forms” contributing to the aggravation of social isolation and the ideals propagated and normalized by such technologies is of crucial importance. Since loneliness has been argued to disproportionately affect youth (DeVega), this paper focuses on the technology that has an allegedly positive correlation with the prevalence of loneliness among this target group: videogames (Lee et al. 389-391).

In a 2018 study, Lee et al. investigate the predictors of game addiction based on loneliness, motivation, and interpersonal competence. Borrowing from Buhrmester et al., the study defines interpersonal confidence as a person’s ability to initiate interpersonal interactions; assert what they want; disclose personal information; elicit and receive emotional support from others; and manage conflicts in close relationships (997-8). Examining a group of 251 college students with an average age of 27.9 years old (385), Lee et al. prove that interpersonal competence “significantly buffered the indirect effect of loneliness…on online game addiction” (381). As the scholars assert, online game addiction, a “previously non-existent” problem of the age of technology, has been recently added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) with a “condition for further studies,” establishing it as an unofficial mental disorder (Lee et al. 381). As such, the study maintains that online game addicts experience “poor mental health, such as depression and anxiety, poor attention, interpersonal deficiency, aggression, and low academic achievement” (382). Finally, Lee et al. draw a triangular connection among loneliness, interpersonal competency, and online game addiction. According to them, individuals who lack social skills prefer online over offline social interactions, as such platforms fulfill their need to protect themselves from feeling socially undesirable, a feeling that has been activated in them as a result of loneliness (384). While the lack of interpersonal competence might not itself cause loneliness; instead, overly self-protective motivation accompanied by loneliness can cause a reduction in interpersonal competence, which will make the gamers even lonelier in the future (Lee et al. 389). To counter the effects of online game addiction on loneliness by encouraging individuals to avoid social interactions, Lee et al. call for two alternatives: First, they believe that we should attempt to activate “promotion-focused motivations,” among lonely gamers. Roughly defined as motivations that push individuals toward making social progress instead of encouraging them to remain inactive to avoid getting hurt, such motivations have been proved to have a direct negative relationship with loneliness (Lee et al. 389-391). The other option, the scholars assert, is to increase the gamers’ interpersonal competence by encouraging them to take part in social activities.

Potential answers to Lee et al.’s call for action will be addressed later in this paper. As discussed at length, the aforementioned study sheds light on the cognitive factors that pave the way for online game addiction. Similarly, other psychological explorations of the connection between loneliness and online game addiction have focused on the socio-economic status of the gamers (Hur 514), the game-design of the videogames (Liu and Peng 1306), and the competitive nature of the videogames (Barnett and Coulson 167) and their relationship with the gamers’ susceptibility to fall victim to online game addiction. However, such studies often fail to explain why certain games have gained exceptional popularity among a specific age group in a specific time in history. In other words, while psychologists are right in insisting that loneliness must be seen as an interior, subjective experience, not an external, objective condition (Shulevitz), subjective studies fall short of dissecting the external conditions that bring about certain changes in the internal feelings of the individuals and, in this case, pushing them toward certain types of videogames. Invoking Cotton’s observation that “not everyone’s loneliness is equal,” (5) this paper will explore the impact of external conditions such as, the eradication of the social space, the atomization of individuals, and the mainstream videogames’ ability to indulge modern users’ propensity for competition and consumerism on creating loneliness among individuals from this age group.

Call of Duty Mobile: Neoliberalism, Individualism, Atomization

Since its initial introduction in 2003, the shooting game series Call of Duty (COD) has been consistently among the most popular videogames. A 2023 study shows that 18% of all (surveyed) gamers (roughly equating to 118 million players, 26 million of whom reside in the US) are COD players. In 2019, Activision Publishing Inc., the designing company of the game series, released an online version of the game designed specifically for mobile phones called Call of Duty Mobile (hereafter CODM), which has attracted around 57 million monthly active users (Curran). What is particularly different about this version of the game is that, unlike the computer editions, players of this series do not follow any specific storyline. Instead, the gamer, whose avatar lands on an island after jumping off a plane, is supposed to compete with 99 other players in every session of the game. The winner is the player that manages to survive until all the other players are killed. While killing the enemy is the basic logic of almost any shooting game, what makes CODM an interesting case study for this paper is the hyperbolic, obsessive “last-man-standing” world-view that the game foregrounds and encourages. While the game’s lack of a story line (deliberately or not) tries to disconnect the players from any sense of history, its individualistic rhetoric, symbolically reflected by the metaphor of the island on which the competition takes place, is in many ways reminiscent of the neoliberal context out of which it has been born.

In a 2022 article, Henry A. Giroux points out the eradication of the public space, where individuals can make offline social contact with each other, under neoliberalism in the 21st century (“The Nazification of American Society”). This has exacerbated the problems of loneliness in the American society, usually justified as “a reflection of private and personal troubles” (DeVega). However, as George Monbiot rightly asserts, the structural changes in the past few decades, such as the closure of factories or the replacement of public transportation by personal vehicles and cinema by online streaming platforms, cannot alone account for the mass isolation that has plagued modern societies. These structural changes, Monbiot suggests, “have been accompanied by a life-denying ideology, which enforces and celebrates our social isolation”. According to Monbiot, the neoliberal engine that runs the modern economy feeds on an ideology of competition and individualism propagated by mass media that prioritizes individual financial growth over collective well-being. Given that research has proved that TV can drive competitive aspirations (Bruni et al. 221-222), imagining a similar impact from videogames is not impossible, though more empirical research is required to prove this hypothesis.

In a 2019 study of another popular shooting video game, BioShock Infinite (Irrational Games, 2013), Pérez-Latorre et al. identify details from the gameplay of the game that closely resonate with the neoliberal values prevalent in the 21st century American society. Their close analysis is also useful to the discussion of this paper, as many of the themes presented in BioShock Infinite can be found in CODM. The players of both games are encouraged to create “the most efficient and effective character possible,” in order to win a battle whose main logic is that “the victory of some is inextricably linked to the defeat of others” (Pérez-Latorre et al. 790). According to Andrew Baerg, strategic character choice and creation based on constant practices of self-surveillance is a key neoliberal element apparent in such role-playing games (Voorhees et al. 164). Moreover, both BioShock Infinite and CODM encourage their players to search the map to find and pick anything that can make their avatar stronger. The more items the character collects, the better their chances are to win the game. Doing so, Pérez-Latorre et al. argue that the games give their users an experience similar to “visiting a supermarket” in a situation where there are no rules and everything is free for taking (792). This, they believe, “connects with how consumerism is conceptualized under neoliberalism, where buying and owning goods is a way of constructing one’s own identity” (793). Good neoliberal citizens, as Nicholas Rose suggests, are consumers who “are constituted as actors seeking to maximize their ‘quality of life’ by assembling a lifestyle through acts of choice in a world of goods” (162). Interestingly, the players of CODM have shown to be 28% more willing to buy the products advertised while playing than the average consumer (Curran).

Perhaps, as mentioned before, what makes CODM unique as a new generation of games made for a new generation of gamers is its effort to introduce a dystopian image of a “post-social” world in which an ongoing war of “every man against every man” (Monbiot) haunts every aspect of social life as the only imaginable future for humanity. After all, as Charles W. Milles suggests, “men live in second-hand worlds,” their experiences being “selected by stereotyped meanings and shaped by ready-made interpretations.” Milles’s assertion that, “these received and manipulated interpretations decisively influence such consciousness as men have of their existence,” coupled with the fact that, “a need to belong drives our thoughts, emotions, and interpersonal behaviors,” (Lee et al. 382) make it crucial not only to dissect the role of mainstream videogames in spreading the “life-denying” ideology against which Monbiot warns but also to search for alternatives that do not reiterate the same ideology and practices.

Play the Knave: “Theatre-Themed” Mimetic Interface Videogames as Social-Based Interventions

Considering the dangerous repercussions of addiction to mainstream online games for the isolated gamers and the liberal society in which they live, this section explores the potential of mimetic interfaced videogames as alternatives by focusing on the specific case of Play the Knave, a video game designed by Gina Bloom et al. at the University of California, Davis. I will argue that Play the Knave can not only reduce loneliness in gamers by giving them the opportunity to increase their interpersonal competence but also lead them out of the “moral coma” that Leo Lowenthal warns comes as a result of a disconnect with history (176).

As discussed at length in the first part of this paper, there exists a positive correlation between loneliness and the lack of interpersonal competence in individuals. Further, there is a negative correlation between a person’s interpersonal abilities and their vulnerability to online game addiction (Lee et al. 389-391). Therefore, it goes without saying that if an alternative video game is supposed to reduce loneliness among its users, it should avoid making them any more addicted to gaming. Accordingly, such a video game should encourage group activities and offline social interaction, things that are meaningfully missing from mainstream videogames, where any form of social interaction takes place merely on online venues.

In their 2022 exploration of potential ways to reduce loneliness among old adults in America, McDonald et al. suggest that “theater-based interventions” can reduce loneliness in this demographic group by fostering their social connectedness and improving their social cognition (6). According to them, “the process of character creation and performance inherent in theatrical performance actively recruits social cognition, through which repeated engagement has the potential to foster improvements by strengthening underlying brain networks” (5). Observing that theater-based interventions have become increasingly popular in recent years as a way to promote healthy cognitive aging by offering complex, dynamic, and mentally stimulating activities[3], McDonald et al. believe that such practices can effectively diminish social isolation among older adults by providing them with “complex and varied social tasks” (1). While they assert that “no study has yet specifically examined changes in social cognition in older adults partaking in theater-based interventions” (5), I believe Lee et al.’s discussion on how reducing loneliness can increase interpersonal competence can theoretically support their hypothesis, albeit considering age differences between the two study groups. While McDonald et al.’s invitation to employ theater-based interventions as tools for reducing loneliness mainly addresses the problem of social isolation among older adults and would thus probably be less effective with a younger generation, I propose that, once adapted/translated via videogames, their theory can in fact reduce the loneliness caused by online game addiction among younger adults. To prove my point, I draw attention to the case of a theater-themed video game called Play the Knave.

Developed in 2015 by Gina Bloom and her team at UC Davis’s ModLab, Play the Knave is a mimetic interface game that takes advantage of the motion capture technology of Microsoft Kinect to help its users design and perform Shakespearean plays (Bloom, What’s Past is Prologue). Observing Microsoft’s innovative show in the E3 Expo in 2013, where they introduced Kinect for the first time, Bloom suggests “[Kinect] is a theatrical technology in which spectators are as much a part of the gaming experience as players. It welcomes spectators to play vicariously” (Bloom, Gaming the Stage 225). Bloom argues that a session of Play the Knave is itself a theatrical event, with players being spectators of their own creation (Gaming the Stage 236), and the spectators actively engaging with the plays through reacting to the players’ performance in different ways (Gaming the Stage 235). While revived by the social nature of Kinect technology, Bloom argues that the practices of ludic involvement of the spectators with what is going on stage have deep roots in the commercial theaters of the 15th-century England. “If in the early modern period… the theater was a gaming platform,” she says, “then in today’s living rooms and public leisure venues, games are becoming theatrical platforms” (Gaming the Stage 224). While Bloom’s emphasis is on the commercial application of vicarious play for videogames, as she maintains that “spectators are an untapped market for gameplay,” (Gaming the Stage 232) I argue that mimetic interface games, such as Play the Knave, which consider the audience as an integral part of the gaming experience, are good examples of games as theater-based interventions. Such games, I believe, can increase their users’ interpersonal competence by putting them in constant yet safe social contact with others in offline venues and, thus, can effectively reduce loneliness among the players. Bloom’s observational research conducted at “over two dozen installations” (Gaming the Stage 235) of the game in different educational and non-educational venues clearly shows the heightened social interactions that players and spectators experience during a session of Play the Knave, something that is absent from most of today’s mainstream videogames, including CODM.

Whether or not this was a goal in the minds of the creators of the game, Play the Knave can protect its players from the harmful neoliberal values, omnipresent in the gameplay of many mainstream games. In other words, the game avoids repeating the rhetoric of loneliness and competition embodied by games such as CODM. Familiarizing its players with timeless literary works through social engagement in theatrical performances of those stories, Play the Knave counters CODM’s efforts to remove a sense of history from the game. Playing any of the Shakespearean plays that they choose, the players familiarize themselves with the context of that specific theatrical performance. They are by no means thrown onto a deserted island. Moreover, as they play, both players and spectators get to comment on the quality of the performance that has been recorded and can be edited and shared. As Bloom explains:

Because the machine does not give players feedback on their performance, they either judge it for themselves or seek judgment from other human observers in the ambient space: their playing partners or spectators. And these other audiences are empowered to give such feedback because their views are in no way superseded by the authority of the machine. In Play the Knave, the job of evaluating player performance is outsourced to the live, physical audience in the room, just as is true in actual theater. (Gaming the Stage 236)

This further empowers the game as a tool for social intervention, following McDonald et al’s observation that “one of the most promising features of theater-based interventions is that they provide the practical opportunity for frequent social interactions” (5).

Finally, as Bloom’s experience of using Play the Knave in English classrooms in South African schools has proved, the game gives its players a chance to make a connection between the game and their own life, thus enhancing their critical thinking abilities. Bloom suggests that, as the students are constantly aware that they are playing a game, such a connection can be safely made, helping the them to reflect on serious themes, such as jealousy, misogyny, and racism through their unique perspective while keeping a distance with the potential harms of engaging with these themes outside a ludic group activity (Bloom et al., “Play to Learn” 15).

While further research is required to prove the efficiency of Play the Knave and similar mimetic interface games in reducing loneliness and, in effect, game addiction among young gamers, the manifold potential benefits of such scholarship as well as the urgency of the matter, discussed at length in this paper, make the conduct of such research a worthy endeavor.

Conclusion

The findings presented in this paper underscore the critical role videogames can play in either exacerbating or alleviating loneliness in modern society. While mainstream online games like Call of Duty Mobile perpetuate neoliberal ideals of hyper-individualism and competition—ultimately destroying the “essence of humanity,” our “connectedness” (Monbiot)—games such as Play the Knave demonstrate the potential for fostering community and interpersonal competence through innovative, theater-based approaches. The hyper-competitive environment of many mainstream games fragments the public sphere, weakening what we once called the “commons.” Considering George Monbiot’s observation that “all other health problems become more prevalent when connections are cut”, it is imperative to nurture collaborative, creative, and social experiences. As I argued earlier in this paper, theater-themed mimetic interface games can challenge the isolating tendencies of traditional online gaming. They also provide a powerful tool for addressing the growing crisis of loneliness. Although the commercially released software for Kinect may not fully realize the theatrical potential of the hardware, the technology itself still holds immense promise for fostering connectedness and shared experiences. As Bloom would also agree, future game design should embrace such possibilities, prioritizing collective engagement and community-building to promote mental health and social well-being in an increasingly disconnected world.

[1] See Bloom et al.’s What’s Past Is Prologue

[2] See the introduction sections in Lee et al. “Loneliness” and McDonald et al. “Theater-Based Interventions” and Shulevitz’s “For the First Time in History”.

[3] See Noice et al.’s “Theatre Arts for Improving Cognitive and Affective Health”and Noice and Noice “A Theatrical Evidence-Based Cognitive Intervention for Older Adults”.

Works Cited

Barnett, Jane, and Mark Coulson. “Virtually real: A psychological perspective on massively multiplayer online games.” Review of General Psychology 14.2 2010, pp 167-179.

Bloom, Gina, and Lauren Bates. “Play to learn: Shakespeare games as decolonial praxis in south african schools.” Shakespeare in Southern Africa, vol. 34, no. 1, 3 Jan. 2022, pp. 7–22, https://doi.org/10.4314/sisa.v34i1.2.

Bloom, Gina, Buswell, Evan. What’s Past Is Prologue – Experimenting with Shakespeare: Games and Play in the Laboratory, shakesperiment.tome.press/chapter/whats-past-is-prologue/. Accessed 31 May 2024.

Bloom, Gina. “Videogame Shakespeare: enskilling audiences through theater-making games.” Shakespeare Studies 43, 2015, pp. 114-9.

Bruni, Luigino, and Luca Stanca. “Income Aspirations, Television and Happiness: Evidence from the World Values Survey.” Kyklos (Basel), vol. 59, no. 2, 2006, pp. 209–25, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.2006.00325.x.

Buhrmester, Duane, et al. Five Domains of Interpersonal Competence in Peer Relationships.

Cotton, Jess. “Introduction: Loneliness and Technology.” New Formations, vol. 109, no. 109, Oct. 2023, pp. 5–9. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.3898/NEWF:109.01.2023.

Curran, James. “Call of Duty: Mobile Player Profile.” Call of Duty: Mobile Player Profile, 21 Nov. 2023, www.activisionblizzardmedia.com/insights/blogs/2023/11/call-of-duty–mobile-player-profile#:~:text=Call%20of%20Duty%3A%20Mobile%20has,audience%20for%20advertisers%20and%20brands.

DeVega, Chauncey. “America’s Epidemic of Loneliness: The Raw Material for Fascism.” Salon, Salon.com, 3 Jan. 2023, www.salon.com/2023/01/03/americas-epidemic-of-loneliness-the-raw-material-for-fascism/.

Fromm-Reichmann, Frieda. “Loneliness.” Contemporary Psychoanalysis, vol. 26, no. 2, 1990, pp. 305–30, https://doi.org/10.1080/00107530.1990.10746661.

Giroux, Henry. “The Nazification of American Society and the Scourge of Violence.” CounterPunch.Org, 14 Oct. 2022, www.counterpunch.org/2022/10/14/the-nazification-of-american-society-and-the-scourge-of-violence/.

Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan: The Matter, Forme, & Power of a Common-Wealth Ecclesiastical and Civill. 1st ed., The Floating Press, 2009.

Hur, Mann Hyung. “Demographic, habitual, and socioeconomic determinants of Internet addiction disorder: an empirical study of Korean teenagers.” Cyberpsychology & behavior 9.5 2006 pp 514-525.

Lee, Ji-yeon, et al. “Loneliness, Regulatory Focus, Inter-Personal Competence, and Online Game Addiction: A Moderated Mediation Model.” Internet Research, vol. 29, no. 2, Apr. 2019, pp. 381–94. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-01-2018-0020.

Liu, Ming, and Wei Peng. “Cognitive and psychological predictors of the negative outcomes associated with playing MMOGs (massively multiplayer online games).” Computers in Human Behavior 25.6 2009, pp 1306-1311.

Lowenthal, Leo. “Atomization of Man.” False Prophets, 1st ed., vol. 3, Routledge, 1987, pp. 175–85, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203792322-11.

McDonald, Brennan, et al. “Theater-based interventions as a means of reducing social isolation and loneliness, facilitating successful aging, and strengthening social cognition in older adults.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 15, 28 June 2024, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1364509.

Mills, C. Wright. “The Cultural Apparatus.” Cultural Apparatus, 30 Aug. 2011, culturalapparatus.wordpress.com/culture-and-politics-the-fourth-epoch/the-cultural-apparatus/.

Monbiot, George. “The Age of Loneliness Is Killing Us | George Monbiot.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 14 Oct. 2014, www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/oct/14/age-of-loneliness-killing-us.

Nilsson, Brita, et al. “Is Loneliness a Psychological Dysfunction? A Literary Study of the Phenomenon of Loneliness.” Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, vol. 20, no. 1, Mar. 2006, pp. 93–101. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2006.00386.x.

Pérez-Latorre, Óliver, and Mercè Oliva. “Videogames, Dystopia, and Neoliberalism: The Case of BioShock Infinite.” Games and Culture, vol. 14, no. 7–8, Nov. 2019, pp. 781–800. DOI.org (Crossref), https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412017727226.

Rose, Nikolas. “Governing Enterprising Individuals.” Inventing Our Selves: Psychology, Power, and Personhood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. 150–168. Print. Cambridge Studies in the History of Psychology.

Shulevitz, Judith. For the First Time in History, We Understand How Isolation Can Ravage the Body and Brain.

Voorhees, Gerald, et al. Dungeons, Dragons, and Digital Denizens : The Digital Role-Playing Game. Continuum, 2012. World Health Organization. “Advocacy brief: Social isolation and loneliness among older people.” World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland (2021).

Read more at By Navid Jalali Asheghabadi.

Articles, Cultural PedagogyRelated News

News Listing

By Maya Phillips ➚

Failure to Reeducate: Perpetuations of Cultural Fascism in Post-War Germany

Articles, Cultural Pedagogy, Public Pedagogy

February 9, 2026

By Rosemary Kasiobi Nwadike ➚

Feminist Miseducation in the Afro-West: Examining (In)Formal Gender Indoctrinations

Articles, Education, Resistance, Social Justice

July 11, 2025