“From Vietnam to Palestine”: Articulating Possibilities and Practices of Radical Solidarities Between Palestinians and Vietnamese Refugees

Introduction

This paper seeks to remember the intimate connections between the anticolonial movements among Palestinian and Vietnamese diaspora, as well as reflect upon the significance of these transnational solidarities in the context of today’s ongoing Palestinian genocide. Because scholarly thinking on the genocide is still developing as we collectively mourn and bear witness to the atrocities unfolding in Gaza and the West Bank, and because the efforts of scholars, students, and organizers to critique Israel’s settler-colonial projects are being silenced through neoliberal regimes of state-sanctioned censorship, this paper makes use of many non-scholarly articles, blog posts, and posts on social media to make sense of what is happening in relation to Palestine. In doing so, this paper is structured into three sections. In Section One, I explore the rich histories of co-resistances that were facilitated between Vietnam’s and Palestine’s anticolonial and national liberation movements during the Cold War. In Section Two, I examine the failures of critical refugee studies and Asian diasporic studies in remaining silent over genocide, and I articulate how this failure to ‘speak out’ in academia is intimately linked to how the university works to undermine practices of radical solidarity between Palestinians and Vietnamese refugees. Lastly, in section three, I turn towards grassroots organizing and resistance movements within Asian communities in the U.S. and among students at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario in order to think about how we—as Vietnamese refugees and their descendants—might once again engage in a radical politics of refusal and solidarity with Palestinians who are (and havebeenfor decades) facing what Patrick Wolfe describes as colonial “logics of elimination” (Wolfe 387). Thus, by weaving together threads of transnational anticolonial resistances between Vietnam and Palestine, I argue that we can begin to articulate the ways in which Vietnamese refugees and Indigenous Palestinians have—and are still—engaging in a radical praxis of co-resistance and shared solidarity against colonial empire.

A Brief History of Vietnamese Palestinian Co-Resistance and Solidarity

I borrow the use of the word “co-resistance” from Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar Leanne Betasamosake Simpson to describe how the anticolonial resistance movements of both Vietnamese refugees and Palestinians are intertwined. This is because, as Simpson says, to build “constellations of co-resistance” is to forge meaningful solidarities with “communities that are fighting different aspects of the same system” in ways that mutually work towards our collective and eventual liberation from settler-colonial empire (Simpson 28). Indeed, abolition feminist scholar Angela Davis argues in Freedom is a Constant Struggle that connections of international solidarity exist between the struggles of Black people in the U.S. and Vietnamese people who resisted American invasion and occupation, as well as with Palestinians who are currently resisting Israeli apartheid and settler-colonialism (Davis 53). This rich history of co-resistance and radical solidarity between Vietnamese and Palestinian people will be the focus of this section, as drawing parallels between our experiences of colonial violence can make our resistance movements collectively stronger. Moreover, in drawing parallels, we can also work towards recognizing global and transnational systems of power and how they work in tandem to produce systemic violence both at home and abroad.

In thinking about the parallels between the Palestinian and Vietnamese people, we can first look at how Palestine and Vietnam were linked through the American Cold War imaginary and its rhetoric of “socialist containment” (Phu et al. 83). In Cold War Camera, Vietnamese Canadian scholar Thy Phu recalls how during the mid-1960s, Russia supplied weapons to Egypt and Syria for use in border clashes with the recently established State of Israel (Phu et al. 83). The United States, perceiving this to be an intentional expansion of Soviet communist ideologies, chose to provide Israel with military support against an alliance of Arab countries. After the Six Day War of 1967, in which Israel expanded its annexation of Palestinian territory against international law, the United States agreed to sell phantom jets, which were used in the Vietnam War, to Israel, marking the beginning of a “sharp increase in US military, economic, and political aid to Israel at the expense of Palestinian self- determination” (Phu et al. 83). Coordination between the American and Israeli governments over war tactics are similarly articulated; Israel used US-produced napalm on Arab soldiers during the Six Day War after Israeli military leader Moshe Dayan visited American troops in 1966 to study counterinsurgency tactics used in Vietnam (Johnson 365). Thus, Vietnam and Palestine were connected via the US’s Cold War policies, in which both of their populations were subjected to and resisted the same weapons and technologies of war shared between their colonial and imperial oppressors.

Critical refugee studies scholar Evyn Lê Espiritu Gandhi reminds us that these shared experiences of coloniality and imperialism did not cease even after the Vietnam War formally ‘ended,’ and as millions of Vietnamese refugees fled Southeast Asia and resettled in countries like Canada and the US. Gandhi argues that the US intervention in Vietnam is not solely a Cold War phenomenon, but also part of a “longer genealogy of American westward expansion across the North American continent, across the Pacific Islands (Guam), and into Asia—both Southeast Asia (Vietnam) and West Asia (Palestine)” (Espiritu Gandhi 52). In other words, by geographically triangulating Vietnam, Palestine, and so-called ‘North America,’ and therefore the Vietnam War and its exodus of refugees, the ongoing Palestinian genocide, and the ongoing settler-colonization of Indigenous peoples and lands on Turtle Island, we get a comprehensive understanding of how the settler-colonial empire’s activities of death-making and displacement are connected. Through this logic, both the Vietnam War and the Palestinian genocide are intimately tied to ongoing processes of land theft, dispossession, and genocide that occur within the settler-state’s imaginary sovereign borders on Indigenous land. Furthermore, through imperial projects like the US invasion and intervention in Vietnam, the US can displace populations across the globe and then resettle them on American soil as a means of further colonizing Indigenous lands and undermining Indigenous sovereignty in so-called ‘North America.’ In short: Palestinians, Vietnamese refugees, and Indigenous peoples across Turtle Island are also connected through shared encounters with the same settler-colonial empire globally.

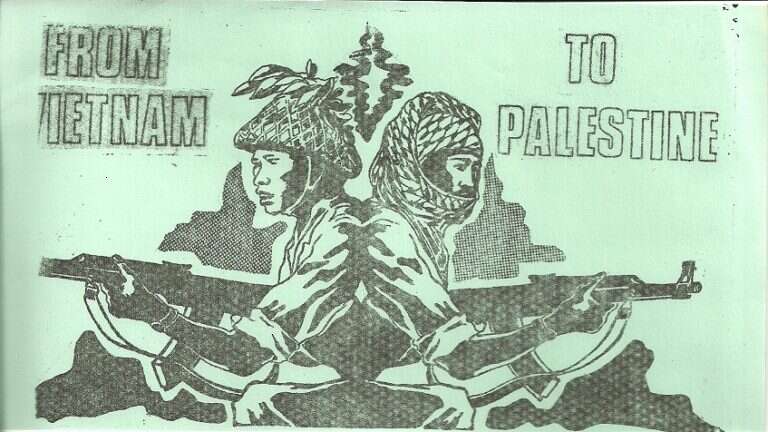

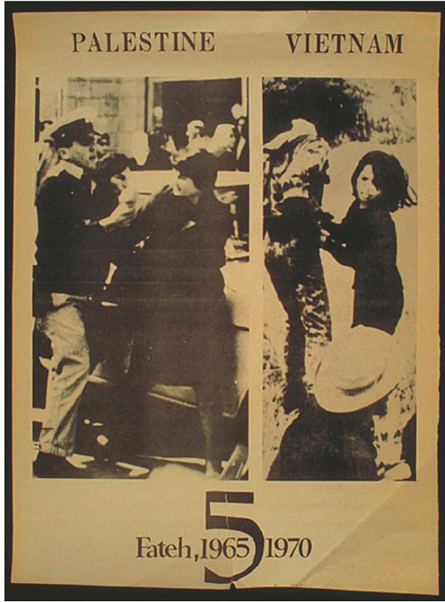

Meanwhile, Palestinian and Vietnamese freedom fighters sought out points of commonality and connection themselves, drawing rhetorical and visual parallels between their respective anti-imperialist and anticolonial liberation movements throughout the 20th century. In 1970, the Palestinian political party Fatah (which remains one of the leading political factions within the Palestinian Liberation Organization) distributed flyers drawing similarities between the Palestinian and Vietnamese national independence movements by drawing upon the “icon of the revolutionary Vietnamese woman” (Phu et al. 84). Aiming to capitalize on Vietnam’s international visibility during the Vietnam War, the comparatively overshadowed Palestinian liberation movement sought parallels with the northern Vietnamese resistance against the United States to garner international support and solidarity (Phu et al. 84).

Figure 1. A poster from the “Fatah 5” Series commemorating five years of Fatah’s prominence in the Palestinian struggle (Phu et al. 88).

As Thy Phu et al. argue, this gendered figure of resistance was chosen not only because it garnered sympathy from an international audience, but because it highlighted the intensity of the Vietnamese struggle against colonial imperialism: “the Vietnamese were so determined to protect their homeland and children from Western aggressors that even women were moved to join the fight” (Phu et al. 88). Moreover, it emphasized the integral role that Palestinian women have played throughout the Palestinian National Liberation Movement (Phu et al. 88).

Palestine and Vietnam were often recognized by diverse organizations not only as parallel struggles that were interconnected, but also two sides of the same single struggle for anticolonial and imperial liberation. Indeed, the Syrian Baath party, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the Afro-Asian Latin People’s Solidarity Organization, and the Weather Underground all linked Palestine and Vietnam (and often Black liberation across North America too) as “inseparable struggles against global imperialism” (Johnson 364). And as Rebecca C. Johnson reminds us, these linkages were not merely rhetorical but also material; as early as 1963, Fatah fighters had taken trips to Vietnam to learn resistance methods, and in 1970, Fatah representatives undertook a two-week tour of Hà Nội, visiting factories, bases, training camps, schools, and North Vietnamese generals (Johnson 364-365). Thus, through a combination of shared encounters with colonial oppressors who themselves linked Vietnam and Palestine through Cold War policies, rhetorical and material solidarities between the Palestinian and Vietnamese liberation movements, as well as international recognition from organizations that understood Palestine and Vietnam to be mutual sites of a shared anti-imperial and colonial struggle, these histories and lineages of radical solidarity between Palestinians and Vietnamese people have been widely documented and woven into existence. And yet, as I argue in the following section, these threads of anticolonial resistance are easily subjected to collective forgetting—especially from Vietnamese refugees who have resettled on contested Indigenous land, who have found work in academia and in fields of so-called ‘radical political thinking and praxis,’ and who must navigate politics of inclusion and exclusion—as well as complicity in being silent over genocide.

Silences Across the Neoliberal University

Although Vietnamese people, Palestinians, and their descendants share and inherit a history of mutual and radical solidarity, it is also important to attend to the silences, absences, and gaps within these relations, especially in the present moment in which Israel has been charged with perpetrating genocide (and has been doing so for decades) against Palestinians in Gaza. It is no longer tenable to overlook the fact that there has been a tendency amongst our refugee kin in academia—and most surprisingly in fields such as critical refugee studies, critical race studies, and Asian diasporic studies—to become complicit and silent on the matter of Israel’s practice of genocide against Palestinians.

In an essay dedicated to Asian Americans, Vietnamese American scholar Viet Thanh Nguyen tells us that although self-defense is necessary to ward away those violent attempts to kill and reduce our people to that of human animals—and necessary as well for storying ourselves into the past and future, the danger of self-defense is in “becoming absorbed by our own victimization, and through insisting so strenuously on our humanity, becoming incapable of acknowledging our inhumanity—or the humanity of our adversaries” (Viet Nguyen). Indeed, by creating and theorizing literature, Asian Americans have worked to resist “the Oriental double, defend ourselves, and fight for inclusion” (Viet Nguyen). And yet, as America projects its power globally, Asian American literature has become a “subset of imperial literature,” which might explain why many of us are censoring ourselves on the topic of Palestine. In another essay, Vietnamese refugee and scholar Vinh Nguyen echoes similar frustrations, saying “I keep waiting for major research centers, big professional associations, and respected journals to say something about what has been happening in Gaza. For the international refugee studies community to rally around the very people they research and write about. After all, this genocide is happening to refugees… what I see is more publications, more conferences, more summer schools” (Vinh Nguyen).

Echoing the critiques of Viet Thanh Nguyen and Vinh Nguyen, I am critical of the ways in which academic fields like critical refugee studies and Asian diasporic studies (and more) have largely turned away from bearing witness to genocide in Gaza. This is because I am also more broadly critical of this notion of ‘the university’ as an academic institution and space that is built on the promises of free speech and expression. I do not say all this to call out folks or to virtue signal. Instead, I am simply echoing the calls of Asian scholars who, like many other folks that work in/for universities, are watching on as ‘radical’ academic fields and disciplines across the Humanities and Social Sciences continuously fail as litmus tests for refusing and resisting the ongoing displacement, dispossession, and genocide of Palestinian lives. In the words of Vinh Nguyen, “Refugee studies must always be the first call for a ceasefire… or else wither in the genocidal violence to which it won’t bear witness” (Vinh Nguyen).

Of course, I recognize that the ability to ‘speak out’ against genocide within one’s academic institution is also intimately linked to the university’s neoliberal and colonial frameworks, which undergird the university’s policy and decision-making and, most critically, function to undermine practices and possibilities of radical solidarity between Palestinians and faculty/staff/students on campus. Thus, I argue that we can interpret the inaction of critical refugee studies and Asian diaspora studies in mobilizing against Israeli apartheid and colonial genocide through a critique of ‘the university’ as a neoliberal and colonial institution, which recognizes how notions of ‘freedom’ and ‘progress’ are evoked in order to silence calls for boycotting genocide and suppress threads of anticolonial co-resistance and solidarities between Palestinians and other communities like Vietnamese refugees. Much of this thinking has to do with what la paperson calls the “first, second, and third university” (la paperson 36). In A Third University is Possible, la paperson argues that whereas the first university is characterized by an “ultimate commitment to brand expansion and accumulation of patent, publication, and prestige” (la paperson 36), the second university is comprised of ‘liberal’ art colleges and universities, that while may offer meaningful challenges to the academic-industrial complex and seek to nourish the critical thinking skills of its students, “its defining pursuit of questions of art, humanities, and a libertarian mode of critical thinking displaces the possibility of sustained, radical critique” (la paperson 36). Because, while the second university is committed in theory to deconstructing systems of power and transforming the world through critique, la paperson says that “its hidden curriculum reflects the material conditions of higher education—fees, degrees, expertise, and the presumed emancipatory possibilities of the mind—and reinscribes academic accumulation” (la paperson 42). This second university model explains the tendencies and behaviours of universities to silence calls for boycotting Palestinian genocide through neoliberal-colonial frameworks.

On January 4, 2014, the Association of Public Land-Grant Universities (APLU) which represents 219 public research universities, land-grant institutions, state university systems, and related organizations in the US, issued a statement to “strongly oppose the boycott of Israeli academic institutions” in direct response to the American Studies Association’s and the Association for Asian American Studies’ 2013 resolution to support the call for boycotts, divestments, and sanctions (BDS) by Palestinian civil society (la paperson 29). The APLU justified this by avoiding direct mention of the scholarly organizations involved, Palestine, and the exact boycott in their statement, as well as framing the boycott as being detrimental to vague and unspecified “critical projects that advance humanity, develop new technologies, and improve health and well-being across the globe” (la paperson 30). As a result, the APLU seemed to suggest that the BDS movement was ‘bad’ because it somehow suppressed free speech, which was ‘good.’ (la paperson 30). Ironically, the APLU succeeded in suppressing the ability of faculty members and students from freely discussing the Palestinian genocide in public and across hundreds of higher education institutions across the US. It also succeeded in silencing the voices of Asian scholars who were among the first academic associations to call for a boycott of the State of Israel back in 2013.

As it currently stands, institutions of higher education are currently characterized by their accumulation of human capital via student enrollment and tuition fees, their profit margins and investment portfolios in places like Israel’s military-industrial complex (@Toronto4P), and a personal stake in the settler-colonial ‘skills economy.’ It makes sense then, that universities would work to suppress and undermine critical speech against Israel, as well as silence anticolonial resistance and solidarity movements between Palestinians and the academic community, since the presence of decolonial rhetoric and desires on campus are deeply antithetical to the university’s neoliberal and colonial practices of “land accumulation as institutional capital” (la paperson 25). After all, la paperson reminds us that universities are built on land, and especially in the North American context, on “occupied Indigenous lands” (la paperson 26). Thus, students protesting state-sanctioned violence and Palestinian genocide are banned from campus and threatened with expulsion, faculty are dismissed, and others are denied tenure and promotion (Razack). As critical race scholar Sherene Razack says, “dispossession, as scholars of settler colonialism show, is always about the story one tells, as the land is cleared for more white settlers. Colonial projects, like all projects of rule, always go after the storytellers” (Razack).

Imagining Otherwise: Possibilities and Practices of Radical Solidarities

How do we begin to imagine and act otherwise? How can Vietnamese refugees return to the inheritances and lineages of their ancestors, who worked to resist alongside their Palestinian brothers and sisters? How can we refuse our complicity in settler-colonialism, not only here in settler-colonial ‘Canada’ and the US, but also in the occupied territories of Palestine? Evyn Lê Espiritu Gandhi suggests that the challenge for racialized refugees and their descendants will be to “put refugee critiques of the nation-state in conversation with Indigenous critiques of settler colonialism in order to challenge settler colonial states’ monopoly over the [land, rivers, and seas]” (Espiritu Gandhi 190). Thus, in offering real, tangible ways of embodying otherwise, I examine two sites in which Vietnamese and Palestinian people are organizing alongside one another, in hopes of dismantling Israel’s Zionist occupation and forging co-resistances of “decolonial futurities” (Espiritu Gandhi 190).

This first site takes place in Los Angeles’ Chinatown, in which Vietnamese and Asian diasporic communities have worked tirelessly to mobilize their campaigns against community gentrification and displacement in solidarity with Palestinians who are similarly facing dispossession and displacement from Israel’s settler-colonial occupation. In an article featuring a discussion with three organizers from LA’s Chinatown, Richard Lai, Lynn Ta, and Promise Li argue that many residents are organizing in solidarity with Palestinians because they share a “common struggle against global systems of domination: the hegemony of US imperialism, militarized capitalism, settler colonialism, and criminalized migration” (Lai et al.). While I do not conflate gentrification with settler-colonialism, it is true that both are symptoms of life under the same settler-colonial and carceral structures. For instance, the organizers highlight how their plans to secure permanent, affordable housing in a Chinatown apartment building were disrupted when the city of Los Angeles began backroom negotiations with the owner of the building, effectively cutting tenants out of decisions regarding their own housing (Lai et al.). These same politicians recently passed a motion asking the city attorney and Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) to report on whether “the mass dissemination of flyers critical of Israel’s genocide of the Palestinian people should be a criminal misdemeanor constituting so-called antisemitic hate speech, essentially conflating anti-Zionism with antisemitism” (Lai et al.). Moreover, the LAPD which has been tasked with enforcing this motion is also known to routinely train with the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) and import “Israeli military tactics and strategies to use in the urban policing of Black, brown, poor, and unhoused communities in Los Angeles” (Lai et al.). This deadly exchange, the organizers remind us, not only showcases the ways in which state repression is internationalized, but also the importance of local organizing to address anti-carceral, anticolonial, and anti-capitalist resistance movements that are global and transnational (Lai et al.).

The second site takes place here in Hamilton, Ontario at McMaster University. Over the course of 2024, faculty, staff, and students have borne witness to the ways in which the university surveils and polices faculty and students who are organizing against colonial genocide and apartheid. And yet, McMaster students in particular have remained steadfast in their demands for McMaster to boycott and divest from Israeli institutions, acknowledge Israel’s genocidal crimes in Gaza and the West Bank, as well as endorse a framework of anti-Palestinian racism in the institution (@Toronto4P). Recently, I was drawn to an image that was circulating on social media of a campus protest organized a few months ago by McMaster Students for Palestinian Human Rights. In the photo, protestors held up a banner stating the following: “STUDENTS PROTEST AGAINST: VIETNAM WAR (1968), SOUTH AFRICAN APARTHEID (1985), GENOCIDE IN GAZA (2024)” (McMaster Students for Palestinian Human Rights). Here, Palestinian protestors and organizers at McMaster University are drawing on rich histories of coalition-building with other communities in the past—not only with Vietnamese refugees who resisted colonial occupation and invasion in Southeast Asia, but also those who mobilized against the white settler-colonial and apartheid regime of South Africa. Now they are asking these same communities and folks to show up for Palestinians resisting colonial occupation and genocide today. Their actions also demonstrate the capacity of anticolonial organizing to remember, honor, and reflect global and transnational struggles against carceral and militarized capitalism, settler-colonialism, and imperialism. And in doing so, they demonstrate how Vietnamese refugees and Indigenous Palestinians are enacting a radical praxis of anticolonial co-resistance and solidarity across Vietnam, Turtle Island, and Palestine.

Figure 2. Palestinian students protesting genocide at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario (McMaster Students for Palestinian Human Rights).

Conclusion

In conclusion, this paper has sought to explore the intimate connections between the Vietnamese and Palestinian liberation movements, as well as reflect upon the significance of these histories in the context of Israel’s recent escalations in Gaza and the Palestinian genocide. First, I traced the connections and parallels between Palestine and Vietnam throughout a history of the Cold War. Second, I examined a disturbing trend among folks in critical refugee studies and Asian diasporic studies to remain silent on the manner of genocide, despite many Asian folks—including Vietnamese refugees who found work in academia—inheriting these old legacies of solidarity-making with Palestinians. I argued that this can be understood within a framework of higher education as site that (re)produces colonial and neoliberal logics, and therefore silences calls for boycotting genocide. Lastly, in section three I examine organizers from Los Angeles’ Chinatown as well as McMaster University students demanding boycotts, divestments, and sanctions against Israel as a means of discussing liberatory practices and alternatives to complicity in genocide. Therefore, I argue in this paper that by weaving together various instances of transnational, anticolonial refusals across the geographies of Vietnam, Palestine, and Turtle Island, we can articulate how Vietnamese refugees and Indigenous Palestinians have engaged in a mutual, radical praxis of co-resistance and solidarity against global systems of colonialism and imperialism.

Works Cited

@Toronto4P. “McMaster University students have launched their encampment! Their demands are simple: 1. Disclose Investments; 2. Divest from BDS-listed companies, as well as weapons and defence contractors; 3. Academic boycott; 4. Declaration condemning the genocide, suppression of Palestinian speech, and adoption of Anti-Palestinian racism.” Twitter, 5 May 2024, 2:11 p.m., https://x.com/Toronto4P/status/1787183390375944337.

Davis, Angela. Freedom is a Constant Struggle. Haymarket Books, 2016.

Espiritu Gandhi, Evyn Lê. Archipelago of Resettlement: Vietnamese Refugee Settlers and Decolonization across Guam and Israel-Palestine. 1st ed., University of California Press, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520976832.

Johnson, Rebecca C. “Cross-Revolutionary Reading: Visions of Vietnam in the Transnational Arab Avant-Garde.” Comparative Literature, vol. 73, no. 3, 2021, pp. 360–81, https://doi.org/10.1215/00104124-8993990.

la paperson. A Third University is Possible. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Lai, Richard, et al. “From Vietnam to Palestine: A Conversation with Richard Lai, Lynn Ta, and Promise Li.” Spectre Journal, 3 May 2024, https://spectrejournal.com/from-vietnam-to-palestine-solidarity-across-time-and-borders/.

McMaster Students for Palestinian Human Rights. “Image of McMaster Students Protesting Palestinian Genocide on Campus.” Instagram, 27 November 2024, https://www.instagram.com/stories/highlights/18024799094616156/.

Nguyen, Viet Thanh. “Palestine is in Asia: An Asian American Argument for Solidarity.” The Nation, 29 January 2024, https://www.thenation.com/article/world/palestine-asia-orientalism-expansive-solidarity/.

Nguyen, Vinh. “no refuge: a provocation.” Refugee History, 24 October 2024, https://refugeehistory.org/blog/2024/10/24/no-refuge-a-provocation.

Phu, Thy, et al., editors. Cold War Camera. 1st ed., Duke University Press, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478023197.

Razack, Sherene H. “Genocide and Campus Bans on Speech Critical of Israel: Then and Now.” Social Text: Palestine Now, 5 March 2024, https://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/genocide-and-campus-bans-on-speech-critical-of-israel-then-and-now/.

Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. “Indigenous Resurgence and Co-Resistance.” Critical Ethnic Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, 2016, pp. 19–34. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.5749/jcritethnstud.2.2.0019.

Wolfe, Patrick. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research, vol. 8, no. 4, 2006, pp. 387-409, https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240.

Read more at By Futures Futures Futures Collective.

Articles, Resistance, Social JusticeRelated News

News Listing

By Maya Phillips ➚

Failure to Reeducate: Perpetuations of Cultural Fascism in Post-War Germany

Articles, Cultural Pedagogy, Public Pedagogy

February 9, 2026

By Rosemary Kasiobi Nwadike ➚

Feminist Miseducation in the Afro-West: Examining (In)Formal Gender Indoctrinations

Articles, Education, Resistance, Social Justice

July 11, 2025