Scorched Earth and Stolen Bodies: Bridging Crary’s Capitalist Collapse with Coates’ Racial Justice

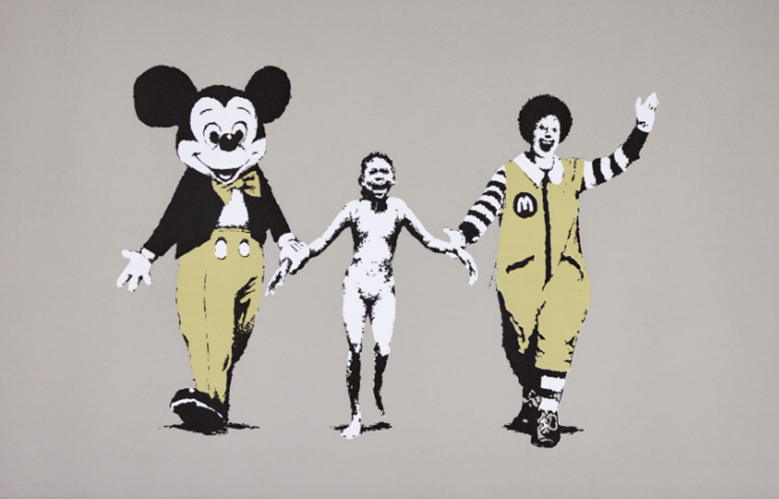

Figure 1. Banksy. “Nepalm” Young girl fleeing Napalm blast, held by Mickey Mouse and Ronald McDonald.

“The Earth is not our creation. It has no respect for us. It has no use for us. And its vengeance is not the fire in the cities but the fire in the sky.”

– Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me, 163

Introduction: Expanding Crary’s Critique of Capitalism

Jonathan Crary’s Scorched Earth offers an impactful critique of the environmental devastation perpetuated by capitalism. Specifically, he underscores the way in which our relentless operation of 24/7 “techno-consumerist” systems erodes the little chance we have for renewal or recovery (4). Crary’s investigation certainly holds merit; however, it could be expanded by addressing the racial/social dimensions of environmental collapse – which are underexplored in his work. Specifically, his investigation does not account for the ways in which marginalized communities (e.g., Black, low-income, and Indigenous communities) are disproportionately affected by ecological crises and the apparatuses of capitalism that sustain them (University of Michigan).

My essay argues that Crary’s critique must be pushed even further to interrogate the ways that racial exploitation is directly connected to environmental devastation. Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me provides an important lens through which to expand Crary’s argument. Coates explains that the American Dream is built on the exploitation of Black bodies – paralleling Crary’s portrayal of capitalism’s exploitation of the Earth. Coates’ metaphor of the automobile as a “noose around the neck of the Earth” critiques not only environmental destruction but also the racial violence embedded in the infrastructure of capitalism (136). Coates’ text asserts that environmental degradation (e.g., sprawl, waste) must not be separated from the history of racial exploitation (Greenbelt Alliance). In expanding Crary’s argument, my essay raises an important question: How can we reimagine environmental sustainability and resistance to capitalism in ways that account for the disproportionate harm faced by marginalized communities?

Crary’s Vision of Environmental Collapse

“A scorched earth is the stifling of hope, the cancelling of the possibility that the world could be restored or healed.” (38)

Jonathan Crary’s Scorched Earth offers a critical and “provocative” examination of the link between capitalist systems and environmental degradation; he argues that the only hope for a habitable future is to dismantle the structures of 24/7 capitalism that govern contemporary living (Powell). Crary contends that the global authority of these systems – particularly the tech-driven “platform capitalism” – is moving the Earth towards ruin (Walsh). He calls for a future that is “offline” and “uncoupled from the world” (1). For Crary, this solution would provide a radical break from the digital and capitalist apparatuses that have flooded every aspect of existence (1).

Scorched Earth argues that capitalism (as it functions today) is an intrinsically disparaging force that commodifies every facet of life – including our social relations and our perceptions of the world around us. Crary’s exploration of capitalism is grounded in the idea that our bodies and senses are now inseparable from the digital economy (36). He critiques how the commodification of human attention (e.g., through the constant surveillance and manipulation of our “gaze”) shapes our interactions and social dynamics (92). As Crary notes, the act of seeing – once a deeply intimate and social engagement – is now co-opted for economic profit (92-104). In one notable passage, he explains the consequence of the “internet complex,” explaining that as it “expands and aggregates, more facets of our lives are funnelled into the protocols of digital networks” (86). In saying this, Crary makes clear that as our world becomes increasingly alienated, it will be stripped of its individuality and commodified by the forces of capitalism.

Crary’s argument extends beyond the economic implications of capitalism; it is a critique of the social, psychological, and existential consequences of living in a world dominated by never-ending construction and consumption. He paints a desolate picture of a world in which all human activity, even leisure, has become a form of labour that feeds into the mechanism of capitalist expansion. This remorseless drive for profit, as Crary maintains, has led to what he calls “scorched earth” capitalism: a destructive quest for resources that devastates the planet and its inhabitants (38).

While the text provides well-articulated insights into the nature of capitalist exploitation, his analysis has been critiqued by scholars like John Walsh for lacking empirical evidence – alongside Henry Powell who critiques the book’s tendency to “move too quickly to fully grasp.” This methodological choice raises questions about the book’s tangible utility for those seeking evidence-based arguments to confront the important issues it eloquently addresses.

Perhaps the most unfortunate shortcoming lies in Crary’s analysis – which overlooks the disparate impact of the “global economy on life support” and the “looming imponderables of the climate crisis” on marginalized communities (27). These groups – predominantly Black, Indigenous, and low-income populations – are often most susceptible to the compounded effects of environmental and capitalist exploitation. With this in mind, their experiences remain largely absent from his critique. In saying this, I assert that Crary’s argument fails to capture a holistic scope of the climate crisis. Nevertheless, this paper aims to provide a more nuanced analysis – acknowledging socio-cultural disparities and offering a more wide-ranging framework for understanding (and responding to) climate crises.

Racial Exploitation as an Extension of Environmental Collapse

In Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates (see Fig. 2) explores the intersection between racial injustice, trauma, and resilience – drawing on Richard Wright’s poem title as a framework for reflection (Kakutani). His critique of the American Dream is equally important and unsettling; throughout the text, Coates unravels its carefully fashioned mȳthos, revealing a foundation built on systemic inequality (Wiktionary). Coates questions American ideals (e.g., progress and wealth) positioning them as agents in a larger cycle of socio-economic and environmental exploitation. He challenges readers to reconsider the costs of capitalism. Specifically, the prioritizing of affluence for the few at the cost of the many – and of the world.

In his examination of racial inequality and environmental degradation, Coates exposes the inherent contradictions within the pursuit of the American Dream. He reveals a stark reality: the affluence promised to some is achieved through the exploitation of both marginalized communities and the natural world. Between the World and Me serves as a glaring critique of a cultural narrative that prioritizes growth and wealth at any cost – advising that a shift is needed; a shift that leads towards collective accountability in the face of our escalating climate crisis. Coates underscores that the foundation of the American Dream has rested on the systemic exploitation of marginalized groups, particularly Black “stolen” bodies (111). Their labour, commodified and dehumanized, became the engine of American wealth.

Figure 2: Ta-Nehisi Coates. Between the World and Me. Worthington Libraries. 4 February 2024.

In Chapter 2, he illustrates this point: “our stolen bodies were worth four billion dollars, more than all of American industry, all of American railroads, workshops, and factories combined” (111). This remark captures the sheer scale of economic dependence on racial injustice. Through Between the World and Me, Coates clearly explains the reality of institutionalized racism – revealing how these cycles of oppression perpetuate poverty and distance many from the so-called ideals of the American Dream.

Coates explains that the American Dream is built upon “generalization” alongside an opposition to deeper inquiry (57). It thrives, he maintains, by “limiting the number of possible questions, on privileging immediate answers” (57). He takes this even further, identifying the Dream: “the enemy of all art, courageous thinking, and honest writing” (57). Through Between the World and Me, Coates deconstructs the illusion of upward mobility. This illusion is upheld by the “pillaging of life, liberty, labo[u]r, and land” (10). In saying this, he pushes readers to confront the injustices embedded in a culture, our culture, that values wealth over humanity. Additionally, Coates makes clear that success and progress come at a price: our unremitting drive for expansion continues to exploit Black bodies and destroy the natural world.

Incorporating Coates’ Between the World and Me into Crary’s analysis adds an important dimension, highlighting the intersections of environmental degradation and the exploitation of marginalized communities. This extension enriches Crary’s critique of capitalism and its impact on both society and the planet – setting the stage for exploring how industrial forces, such as the automobile, continue to shape these interconnected crises.

The Automobile as a Metaphor for Capitalism’s Destruction

In Chapter 3 of Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates uses a powerful metaphor: equating the automobile to a “noose around the neck of the earth.” (163). This comparison critiques the environmental harm caused by automobiles while stressing that racial violence is deeply embedded in our current capitalist infrastructure. By drawing a parallel between the car (representing technological progress) and a noose (historically used as a tool of racial oppression), Coates highlights how the American Dream – built on the exploitation of both Black bodies and the natural world – perpetuates harm on multiple fronts. The “sprawl” of urbanization and the reliance on cars are emblematic of an unsustainable system that damages the environment while continuing to disenfranchise marginalized communities (163).

Figure 3: Canva. The Automobile as the “noose around the neck of the Earth.” Inspired by Chapter III of Between the World and Me. Generated Images. 2024.

The noose, an enduring symbol of intimidation, continues to manifest in modern America, as seen in the numerous “noose incidents” reported over the years. For instance, in 2007, NBC News highlighted several incidents: a noose hung outside a professor’s office (see Fig 4), one found in a schoolyard tree, and another placed in a Coast Guard cadet’s bag (The Associated Press). In response to incidents like these, states like Virginia, New York, and Connecticut have enacted laws to criminalize the display of a noose as a threat (Gramlich). Coates’ metaphor, then, becomes even more tangible, urging readers – especially Americans – to reflect on the moral implications of their actions. Just as the noose is wielded as a weapon of terror, so too is the environmental violence perpetuated by practices like driving through “new subdivisions” (163). Coates invites readers to view the car (as a symbol for current systems of industrial exploitation) as a modern instrument of harm.

Figure 4: Noose hung outside Professors Office. New York. 2007. NBC News.

By framing the Dream as “the same habit that endangers the planet” (163), Coates urges readers to confront the ecological costs of their pursuit of comfort and prosperity. In this way, Coates expands upon Crary’s argument, showing that the socio-economic systems we perpetuate are not just unsustainable – they are actively harmful (to the planet and to marginalized communities). Ultimately, Coates encourages readers to confront the precarious link between ecological destruction and systemic injustice; he calls for a necessary shift in the values that shape our world.

Consumerism, Waste, and the Environmental Crisis

Coates further extends Crary’s critique by highlighting how capitalism’s focus on material prosperity deepens the systemic marginalization of racialized communities – promoting a limited view of success, an outlook that prioritizes individual achievement and consumerism over social equity. Coates, through his novel, reflects on the pressure to conform to this ideal, stating, that he “thought that [he] must mirror the outside world, create a carbon copy of white claims to civilization” (57). His remark underscores a sort of racialized expectation that marginalized individuals in America are pressured to assimilate into. This expectation, according to Coates, is defined by whiteness and capitalist values (57-58).

Figure 5: Consumerism Comic. It’s Time to Jump: The Fence Sitters Manifesto. https://itstimetojump.com/21-greed/

In Chapter 1 of Between the World and Me, Coates describes the American Dream with images of “treehouses and the Cub Scouts,” and scents that “smell like peppermint but taste like strawberry shortcake” (14). These fantasies, which often include “pie and pot roast[s]” as well as “white fences and green lawns” (34), symbolize a culture that glorifies materialism and conspicuous consumption (see Fig 5). Through this imagery, Coates critiques how the Dream encourages the accumulation of goods while failing to fulfill deeper human needs (e.g., meaning and purpose). He highlights a “lost essence,” which stems from “the fact that any claim to ourselves, to the hands that secured us, the spine that braced us, and the head that directed us, was contestable” (43). For Coates, true fulfillment is not found in possessions; instead, it can be found in qualities that are free – like autonomy, respect, and recognition (assets that a consumerist culture fails to offer).

Coates explains that the Dream once clung to “horsepower and wind,” but in his analysis of contemporary society, he points to a new phase: “the damming of seas for voltage, the extraction of coal, the transmuting of oil into food,” which has led to an unparalleled “expansion in plunder” (163). In his critique, Coates highlights the escalating exploitation of the planet’s finite resources (such as minerals and fossil fuels) which are ruthlessly extracted without regard for their long-term sustainability. Crary puts forward a similar argument in Scorched Earth, noting that our unchecked consumption is leading our planet away to be “ravaged and plundered” (43). These arguments are confirmed by Linn Persson who details the way in which we have contributed to pollution, deforestation, and habitat loss (1510-1521).

With this said, Coates’ work extends Crary’s critique by emphasizing that the very places where polluting industries and toxic waste sites are concentrated are often those with the least economic or political power (see Fig. 6). This is confirmed by the University of Michigan who investigated the way in which governments targeted minority, low-income neighbourhoods for hazardous waste sites, impacting vulnerable communities (e.g., children, the elderly, and marginalized groups). In framing the Dream as a force that drives overconsumption while also reinforcing racial and social inequities, Coates asks readers to imagine alternative futures; futures where the wellbeing of both the planet and its marginalized peoples is prioritized.

Figure 6: UBC News. The relative difference in air pollution between social disadvantaged and advantaged groups. Dec. 1, 2020.

Reimagining Sustainability and Resistance

In conclusion, my research advocates for a thorough and interdisciplinary approach to the looming climate crises. By combining Crary’s critique of our “techno-consumerist” system with Coates’ understanding of the racial dynamics at work in environmental exploitation, we can consider more comprehensive courses of action for the future (4). To incorporate the voices and perspectives of those most affected by racial injustice and environmental degradation – especially Black and Indigenous communities – academics and activists must keep investigating how systemic inequality shapes ecological policies and practices. In saying this, my paper argues that the future of environmental justice compels scholars to go beyond ambiguous demands for structural change. Instead, solutions must be supplemented by community-driven, anti-colonial, and decolonial practices – recognizing the ways in which marginalized communities have borne the brunt of environmental and capitalistic exploitation. Only by re-envisioning environmentalism through a lens of equity can we hope to build a future where sustainability is not a privilege of the few but a universal right for all.

With this said, I recognize that my investigation has its own limitations. While my essay offers a merging of works by Crary and Coates, I leave unexamined the specific policy implications of such an intersectional analysis. A more holistic examination of how these concepts can be implemented in real-world systemic change (e.g., economic restructuring, environmental justice campaigns, or legal reform) remains an important field of research. Future research might continue this discussion by concentrating on new, relevant cases where racial/environmental justice overlap; perhaps they will also examine tangible applications of these theoretical findings – assessing their efficacy in varied socio-cultural and political contexts.

Furthermore, given the crisis’ worldwide reach, further comparative research across various locales is necessary. In doing so, we may gain a more complex understanding of the way in which capitalism’s environmental cost is unevenly spread throughout the world. Specifically, this could be done by expanding research to incorporate global viewpoints – especially from the Global South.

My essay is, ultimately, a call to action; it asks authors, decision-makers, and citizens to reconsider their approaches to sustainability. In this way, we can continue to challenge all discourses that continue to uphold the exploitation of the planet and its marginalized communities. Considering the climate crisis, we must keep asking ourselves: What does a truly egalitarian future look like? Additionally, how can we – as a society – resist the authority of the apparatuses that continue to hurt our world and its most vulnerable communities? By addressing these issues, we can start laying the groundwork for a system where environmental sustainability and social equity are not just ideals but reality.

Figure 7: Students Supporting Climate Action. Lilia Geho. One Step.September 28, 2022.

Works Cited

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. Between the World and Me. Electronic Book Version. 2015. Penguin Random House LLC. New York. eBook ISBN 9780679645986.

Crary, Jonathan. Scorched Earth: Beyond the Digital Age to a Post-Capitalist World. Verso Books, 2022.

Gramlich, John. “Noose Displays Provoke New State Penalties.” Stateline.org, 6 June 2008.

Greenbelt Alliance. “What Is Sprawl Development?” Greenbelt Alliance, 4 Apr. 2023, www.greenbelt.org/blog/what-is-sprawl-development/.

Kakutani, Michiko. “Review: In Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates Delivers a Searing Dispatch to His Son.” The New York Times, 9 July 2015, www.nytimes.com/2015/07/09/books/review-in-between-the-world-and-me-ta-nehisi-coates-delivers-a-searing-dispatch-to-his-son.html.

Persson, Linn, et al. “Outside the Safe Operating Space of the Planetary Boundary for Novel Entities.” Environmental Science & Technology, vol. 56, no. 3, 2022, pp. 1510–1521.

Powell, Henry. “Review: Jonathan Crary, Scorched Earth: Beyond the Digital Age to a Post-Capitalist World.” Theory, Culture & Society, www.theoryculturesociety.org/blog/review-jonathan-crary-scorched-earth.

The Associated Press. “Noose Incidents Evoke Segregation-Era Fears.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, 10 Oct. 2007, www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna21228709.

University of Michigan. “Targeting Minority, Low-Income Neighborhoods for Hazardous Waste Sites.” University of Michigan News, 19 Jan. 2016, https://news.umich.edu/targeting-minority-low-income-neighborhoods-for-hazardous-waste-sites/.

Walsh, John. “Scorched Earth: Beyond the Digital Age to a Post-Capitalist World.” ASEAN Journal of Research, vol. 1, no. 1, Jan. 2023, Krirk University.

Wiktionary. “Mȳthos.” Wiktionary, 31 Aug. 2023, https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/mythos.

Figure List

Figure 1: Banksy. “Nepalm” Young girl fleeing Napalm blast, held by Mickey Mouse and Ronald McDonald.

Figure 2: Ta-Nehisi Coates. Between the World and Me. Worthington Libraries. 4 February 2024.

Figure 3: Canva. The Automobile as the “noose around the neck of the Earth.” Inspired by Chapter III of Between the World and Me. Generated Images. 2024.

Figure 4: Noose hung outside Professors Office. New York. 2007. NBC News.

Figure 5: Consumerism Comic. It’s Time to Jump: The Fence Sitters Manifesto. https://itstimetojump.com/21-greed/

Figure 6: UBC News. The relative difference in air pollution between social disadvantaged and advantaged groups. Dec. 1, 2020.

Figure 7: Students Supporting Climate Action. Lilia Geho. One Step. September 28, 2022.

Read more at By Alexis Andrade.

Articles, Resistance, Social JusticeRelated News

News Listing

By Maya Phillips ➚

Failure to Reeducate: Perpetuations of Cultural Fascism in Post-War Germany

Articles, Cultural Pedagogy, Public Pedagogy

February 9, 2026

By Rosemary Kasiobi Nwadike ➚

Feminist Miseducation in the Afro-West: Examining (In)Formal Gender Indoctrinations

Articles, Education, Resistance, Social Justice

July 11, 2025