Poisonous Pedagogies and Social Media: The Need for Feminist Discourse When Considering “The King of Misogyny.”

“Feminist critical pedagogy, like critical pedagogy, is concerned with questions of power, equity, and authority in the classroom, but it adds gender as a critical factor into the equation” – Gesa E. Kirsch (1995).

Now more than ever, classrooms have become a place where educators must take their students through processes of unlearning. Through the rise of digital media and ease of access to platforms such as X, Instagram, and TikTok, young people have become increasingly susceptible to coming across harmful, unrestricted content. Recently, we have seen the rise of internet celebrities and influencers, such as Andrew Tate, who promote sexism and misogyny as being inherently masculine, normative behaviours for young boys and men. Unfortunately, these beliefs begin to mobilize quickly amongst students, especially in schools, thus contributing to the attack on women and girls in these spaces. As such, it has become evident that there is a need for critical feminist pedagogy in relation to the protection and resistance of female educators, faculty, and students from toxic hetero-patriarchal ideologies that have spread across educational institutions and throughout the social hierarchy that tells women and girls that “boys will be boys,” or whose silence suggests it. Using the articles Doing Cultural Studies: Youth and the Challenge of Pedagogy by Henry Giroux and Feminist Critical Pedagogy and Composition by Gesa E. Kirsch, I hope to convey the need for critical feminist pedagogy to protect educators and students from hateful and violent gender-based rhetoric that influencers like Andrew Tate promote on their platforms. Through such analysis, this paper will consider Tate’s online persona as the self-proclaimed “king of misogyny” (Frejsjö & Birgersson 7) to highlight how feminist thinking can be a tool of resistance against gender-based violence, the importance of dismantling power relations and hierarchies within the educational institution, and the need for engaging in processes of learning and unlearning to promote gender equity within the classroom.

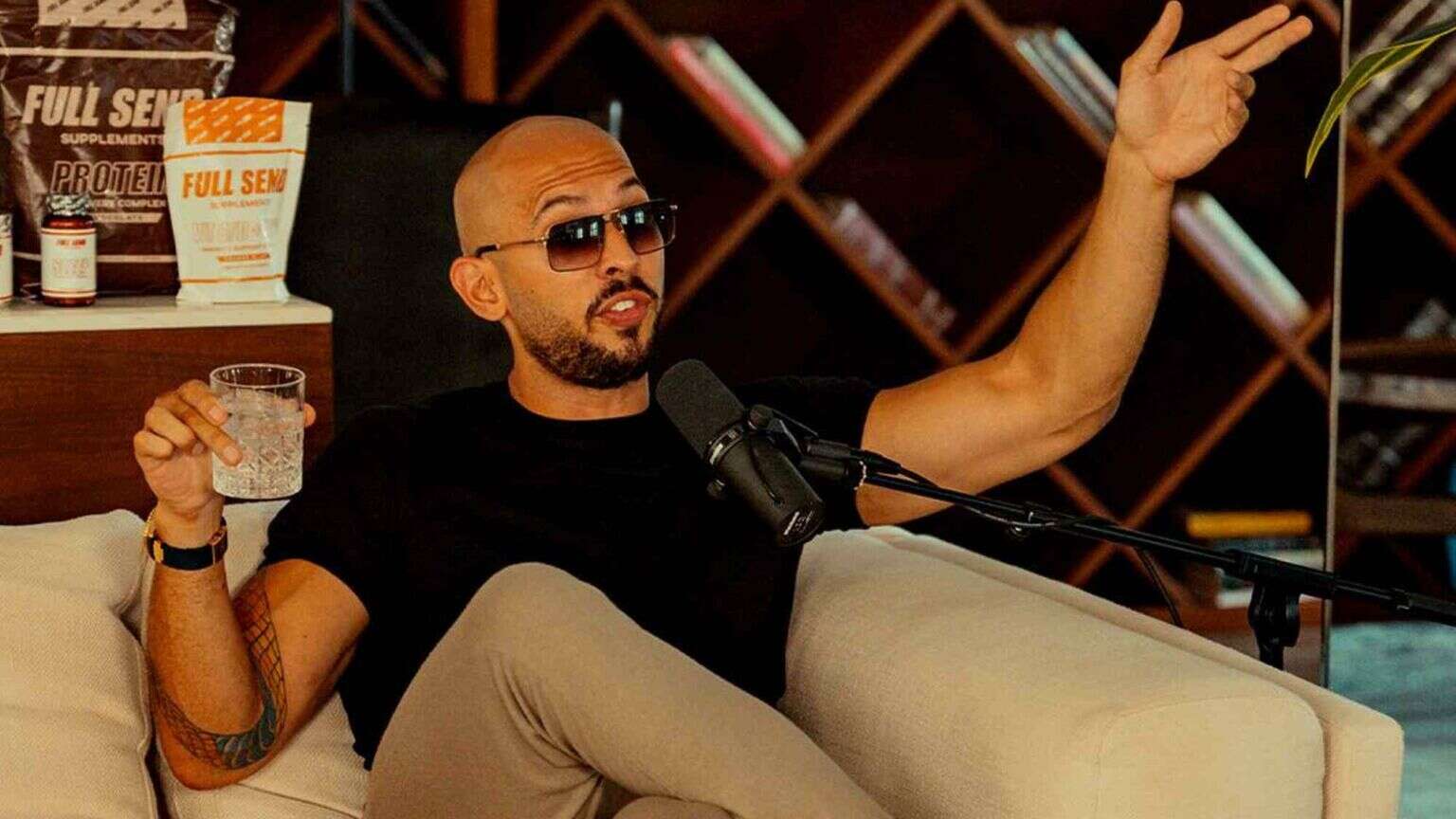

When logging onto social media, we are inundated with updates on our near and distant relatives, memes, and satirical conversations on life. However, in the depths of the internet, a new kind of social content has started to emerge. On the cusp of being pathological, a movement inspired by toxic masculinity and chauvinism has begun to mobilize. The “alpha male bros” have become a global phenomenon, and their content is overtaking the social feeds of those using Xi, Metaii, and TikTok. The so-called “leader” of the alpha male movement is none other than Andrew Tate, the self-proclaimed “king of misogyny”, who quickly made a name for himself across digital and mass media (Frejsjö & Birgersson 7). Andrew Tate, whose followers have donned him with the nicknames “Top G” or “Cobra Tate,” is an American-British former reality TV star and current social media influenceriii (Radford). Famous for boasting his luxurious lifestyle, Tate uses his global platform and “charisma” (or, perhaps more accurately, psychopathy) to spread extremely harmful, misogynistic, and sexist ideologies. To avoid the use of too many redundant adjectives, I will use the phrase “poisonous pedagogies/pedagogy” when referring to his modes of (mis)teaching. Tate’s poisonous pedagogy and discourse tends to focus on notions of success and masculinity, looking at wealth, luxury, and the upholding of gender roles. In his own words, he is teaching people how to escape “the matrix.” In fact, he even has two sites to teach his followers, or his students, how to “escape” and get rich – www.escapethematrix.money and www.tateshustlers.com.iv In fact, both sites offer subscribers the promise of earning $10,000 a month in revenue, through the mentorship of Tate and “other world-class professors” (Tate). As Tate argues that success is most easily attained in a world led by male supremacy and the subordination of women and girls (James), it is safe to assume that none of these “world-class professors” are women. Tate might ask how someone who knows so little oversee teaching people about success, but I pose this very challenge regarding Tate.

What is most concerning is the age of Tate’s audience on social platforms. According to an article written by Will James, Tate’s demographic has predominantly been young boys and men, with ages ranging between primary school and post-secondary (James). In Henry Giroux’s Doing Cultural Studies: Youth and the Challenge of Pedagogy, he states that “youth have once again become the object of public analysis” (Giroux 285). This is important, according to Giroux, because of the social and economic conditions that are impacting this generation of youth, which are inherently rooted in “despair, violence, crime, poverty, and apathy” (Giroux 285-6). Further, young people tend to be more impressionable in terms of how they receive the information that they come across online (Frejsjö & Birgersson 8). As such, those experiencing social and economic disparities are more likely to be receptive to Tate’s poisonous pedagogies and promises of success and wealth, regardless of whether it is at the expense of women and girls. This is especially true when we consider how accessible this kind of propagandic discourse has become. A common theme that we are seeing here is social media and the politics of (mis)information. Giroux states that “there is an issue of how a politics and project of pedagogy might be constructed to create the conditions for social agency and institutionalized change among diverse sectors of youth” (Giroux 289). Andrew Tate has managed to construct a kind of pedagogy that informs and reproduces practices of misogyny as being inherently masculine, which then informs and shapes the performance of one’s masculinity. The politics and project of Tate’s poisonous pedagogy, as seen and received through social media, is informing the beliefs of young boys and men in educational spaces, which contributes to the attack on women and girls in these spaces, both students and educators alike.

It is important to note that as of December 2023, Andrew Tate has been banned from YouTube, TikTok, and all Meta platforms. He is unable to create any new accounts and/or posts on these sites (Frejsjö & Birgersson 7-8). Despite this ban, his content is allowed to be reposted, and the hashtag #AndrewTate has been viewed over 12 billion times, showing that his “fans” still actively seek out his content (Frejsjö & Birgersson 7-8). At one point, Tate was also banned from Twitter—but since the purchase of Twitter (now “X”) by Elon Musk, he has been allowed back onto the platform. When critiqued for reinstating the accounts of Andrew Tate and other controversial figures, Musk issued the following statement: “New Twitter policy is freedom of speech, but not freedom of reach… You won’t find the tweet unless you specifically seek it out, which is no different from the rest of the internet” (X).v At the height of his fame, Tate had a massive 6.9 million followers on X (Radford). As of December 2023, after his unbanning, he currently holds 8.4 million followers, showing that his radical ideologies continue to be consumed and reproduced. According to Giroux, “…the new electronic technologies with their proliferation of multiple stories and open-ended forms of interaction have altered not only the pedagogical context for the production of subjectivities, but also how people “take in information and entertainment”” (Giroux 288). This is particularly interesting when considering the ways in which the advancement of digital technologies and social media have given different characters platforms to circulate their propagandic discourse. What this sounds like, however, is poisonous pedagogies in production – the production of a subjective narrative that spreads false information to impressionable minds, using far reaching modes of communication, such as Andrew Tate implying to his 8.4 million followers on X, some of whom aren’t even old enough to be on the platform, that women need to “bear responsibility” for their role in being sexually assaulted (Radford), among other problematic statements.

As I have used the term “pedagogy” throughout this paper, it is important to offer some contextualization. If we consider critical pedagogy as a cultural practice, it “…deepens and extends the study of culture and power by addressing not only how culture is produced, circulated, and transformed, but also how it is actually negotiated by human beings within specific settings and circumstances” (Giroux 283-4). To understand and combat the spread of Tate’s ideologies of toxic masculinity and the subordination of women, it is important to consider the kind of scholarship that works against it. In Gesa E. Kirsch’s “Feminist Critical Pedagogy and Composition”, she looks at feminist critical pedagogy to “…question the structure of educational institutions, traditional canons of knowledge, women’s roles as teachers and scholars, and students’ responses to female and to feminist teachers” (Kirsch 732). She goes on to argue that the field of feminist critical pedagogy is becoming increasingly more important as its inquiries are concerned with the opportunities, experiences, and successes of women (Kirsch 732). The works of feminist scholars such as Sara Ahmed, Audre Lord, and bell hooks are also powerful resources for educators to engage with to form their own practices of critical feminist pedagogy, as they “…draw on their embodied experiences as a means for producing knowledge about society and power” (Teaching Citational Practice). One of the key pieces of Tate’s messaging to his followers is the attainment of success that can be achieved by following in his footsteps, but particularly through the dismissal and subordination of women in society. Tate’s messaging is contrary to the purpose of critical feminist pedagogy—especially if one is meant to consider the opportunities and successes of women, which are entirely excluded from Tate’s ideal, patriarchal world. Critical feminist pedagogy is important because it fights to make room for women in spaces that hope to push them out, or to exploit and harm them. It combats the ignorant ideologies of patriarchal hierarchies which suppress the successes and agency of women and girls and works to dismantle these beliefs within the classroom.

Building on Giroux’s work on the study of culture and power in relation to critical pedagogy, Kirsch provides a definition of feminist critical pedagogy that works well in contextualizing the very important analysis that must be done in relation to the infiltration of Tate’s ideologies into the minds of young boys and men, as well as into the classroom. She states: “Feminist critical pedagogy, like critical pedagogy, is concerned with questions of power, equity, and authority in the classroom, but it adds gender as a critical factor into the equation” (Kirsch 732). This definition is crucial in understanding the power relations between educational institutions and those who make up the populous within them. Kirsch states that women’s “multiple and simultaneous positionings” within the educational institution are complex and everchanging, and they are given the unfortunate position of having to defend and protect themselves and their students from the problematic politics and ideologies that infiltrate classrooms (Kirsch 726). Though unfortunate, it seems the only way to actively dismantle patriarchy in action. However, dismantling this kind of rhetoric through thoughtful and empowering conversations with both male and female identifying students, is critical to preventing feelings of unsafety within a space that is meant to be educational and informative, but also safe. Parents should not have to fear sending their children to school, and female educators and faculty should not have to experience discomfort or fear when going to work.

Educators around the globe have seen the ways that Andrew Tate’s heteropatriarchal ideologies have quickly mobilized within educational institutions. However, the perpetuation of such violent and hateful rhetoric has become increasingly more prevalent within the smaller settings of the classroom, and parents and teachers both fear the radicalization of young people through their consumption of such messaging (Howse). Though such ideologies can easily be spread in any classroom, this paper focuses specifically on classrooms led by female educators, as it puts them and their female students at a higher risk of gender-based violence. Male students are repeating Tate’s one-liners and reinforcing this beliefs, and female students are feeling the pressure. In an article coming out of the United Kingdom, journalist Imogen Howse shares personal experiences of both educators and female students dealing with their male counterparts’ idolization of Andrew Tate. The article begins with a quote from an eight-year-old boy whose response to a classroom conversation on equal pay between genders was: “Men are superior. We’re better, we’re stronger, we’re smarter than women. That’s just the way it is” (Howse). Initially, the age of the student and the words he spoke were puzzling – what is an eight-year-old doing on social media, indulging in the woman-hating world of Andrew Tate? Gabriel Frejsjö and Noah Birgersson seem to answer this in their article – young people today are growing up with social media as part of their “coming of age” experience (Frejsjö & Birgersson 9). When social media becomes a regular part of one’s day-to-day, they will likely come across social actors whose presence construct and produce varying discourses and ideas that simply cannot always be monitored (Frejsjö & Birgersson 9). Social platforms won’t monitor the activity of each and every user, educators do not have that kind of access, and quite frankly, neither do parents.

This idea is reinforced by Will James, who writes: “Teachers are facing a new challenge that must be addressed: that of online social platforms and how they impact students. Now, more than ever, educators must challenge toxic masculinity within their classrooms…” (James). Using the tools of critical feminist pedagogy, educators have the responsibility to challenge students who share harmful (mis)information from the internet, and to challenge unacceptable behaviour. Educators must actively resist the hateful narratives that enter their classrooms. They must also be aware of the various social characters and content that their students are consuming and engaging with on the internet to appropriately dismantle toxic power relations and disengage the spread of falsified, hateful ideologies that suggest toxic masculinity is inherently normative masculinity. Essentially, beyond having an educational presence, teachers must now also maintain a social presence as well. Further, social media platforms have a responsibility to enforce age restrictions, yet they repeatedly fail in their practices of due diligence. For example, Instagram and X can ask for a date of birth upon registration, but there are no security measures in place to ensure that those registering for these platforms are actually of age – nothing is enforced, and no one is protected. As such, a major implication of these unrestricted platforms is the susceptibility of these young recipients to being exposed to the spread of sexist, harmful rhetoric.

Most troubling is the lack of discipline that male students receive for reinforcing and perpetuating acts of misogyny against their female educators and peers. As patriarchy runs deep in educational institutions, sexist behaviour of boys and men are frequently dismissed as an inherent part of the “boys club” considered fundamental to education, another instance of “boys will be boys.” This is the position held by Gesa Kirsch, and she poses the following questions: How can we empower students? What role does gender play in empowering students (or preventing students from being empowered)?

For one, it is critical that educators deploy their pedagogical tools to work with their male students to recognize the negative influence(s) that they are drawn to, and to resist such ideologies in the future (James). It’s also important that their female students and faculty feel safe and protected within the classroom and the school, ensuring that their pedagogical practices confront and resist the patriarchal policies of the institutions that protect the aggressive behaviours of boys and men—the same behaviours that many argue are inherently masculine (Kirsch). However, it is insufficient to merely tell educators to deploy pedagogical tools and practice as resistance—Kirsch suggests that most female educators have already tried this, but their work and efforts are often ignored or constrained due to the existing power dynamics within the institution (Kirsch 724-5). Instead, institutions must protect their staff and students from the deployment of poisonous pedagogies, especially when these hetero-patriarchal notions of toxic masculinity have always existed within these spaces as a normalized behaviour.

According to Howse, Andrew Tate represents the “empowerment of men” for many of these young boys by fetishizing the luxurious life he lives, and positing that such a lifestyle can only be achieved by disrespecting women. In fact, the lifestyle Tate portrays is merely a marketing tactic to sell one of his “get rich quick” schemes. I argue that, in many ways, Tate’s young fans know his messaging is harmful, but remain empowered by it based on their life experiences and social contexts. Martha Gill suggests that “young men are susceptible to the idea that they are special, deserving and that others are to blame for their problems. And like everyone else, they will behave as badly as society permits” (Gill). However, I argue that this position serves to over-generalize the behaviours of young men, as we know that not all young men find themselves fascinated by Tate and his discourse. Those who fall victim to his messaging should be considered (and analyzed) through the social and economic conditions which have impacted their lives and shaped their identities (Giroux 286). This way, educators have more context surrounding the lived experience(s) of their students and can thoughtfully engage with tools of critical pedagogy and critical feminist pedagogy to better understand what is happening to youth, and why some are more prone to falling for this kind of messaging than others.

One of the things that critical feminist pedagogy does best is provide tools, insights, and resources for the resistance against gender-based violence and existing power relations. It also encourages the process of learning and unlearning for both parties—the privileged and the oppressed, the people who need critical feminist pedagogy and those who believe that they do not. In a journal titled “Why Critical Feminisms?” from Teaching Citational Practice, the authors look at critical pedagogy and feminist pedagogy as two intersectional forms of practice which aim to challenge and inform students on institutional structures of “oppression and relations of power” using “feminist values and praxis” (Teaching Citational Practice). The key piece here is looking back at those characteristics of critical feminist pedagogy that Kirsch highlights in her definition, and examining how poisonous pedagogies “…intersect and contribute to patriarchal structures of oppression and knowledge” as well as how critical feminist pedagogy attempts to dismantle patriarchy by encouraging “students to unveil and critique patriarchy (…) whose many heads include interlocking elements of misogyny, racism, classism, heteronormativity, cisnormativity…” (Teaching Citational Practice). This kind of thinking and engagement with pedagogy encourages processes of learning and unlearning. This idea may be overly general, and it may be problematic and contestable, but the process of learning is relatively straightforward. We receive information, and our brain decides whether it is important enough to retain, despite the validity or invalidity of the information. For example, it is so easy for young boys to retain Tate’s pedagogies, because they are so widespread and pervasive. The process of unlearning, however, is far more complex. Unlearning is the process of shedding the information that has been obtained to make room for information that is logical, truthful, and equitable. Educators and the educational system hold a critical role in working through both pedagogical processes with students—sharing valuable information that should be learned, as well as offering insights on how to unlearn the kind of (mis)information that is believed to be true.

According to Martha Gill, “Tate is not a symptom of too much equality, but too much patriarchy. The real work is getting rid of it” (Gill). The existence of patriarchy is not a new phenomenon, and likely will not become an old phenomenon, at least not in our lifetimes. However, it can be combatted, and educators can attempt to dismantle its prevalence within the classroom to protect themselves and their students. The rise of digital media platforms has been transformative for the pedagogical process, and as much as they bring entertainment, they also allow for the spread of unrestricted information that is quick to mobilize and cause great concern for educators and faculty within educational institutions who hope to work against the radicalization of their students. In this essay, I hope to have conveyed the importance of critical pedagogy and critical feminist pedagogy, as well as their intersection, as forms of resistance against poisonous pedagogies within the educational institution—specifically, the importance of resistance against heteronormative, toxic masculinities and patriarchal power dynamics within the classroom, to protect female educators and students against the ideologies perpetuated by Andrew Tate. In resistance, educators and students can find ways to promote gender equity within these spaces of education, and to work against anti-feminist thinking and hierarchies of gendered superiority.

Works Cited

Frejsjö, Gabriel, and Noah Wernersson Birgersson. “Unpacking Representations of Masculinity in the Digital Age: A Case Study of Andrew Tate’s TikTok Presence: Investigating Content of Andrew Tate as a Catalyst for Shifting Gender Norms and Identity Expression: A Qualitative, Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis of Andrew Tate’s TikTok Influence and Gender Representations.” Karlstad University, 10 August 2023, pp. 7–55, https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1783779/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Gill, Martha. “Andrew Tate Isn’t Feminism’s Inadvertent Bastard Child. He’s Sexism’s Last Gasp.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 8 January 2023, www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/jan/08/andrew-tate-isnt-feminisms-inadvertent-bastard-child-hes-sexisms-last-gasp.

Giroux, Henry. “Doing Cultural Studies: Youth and the Challenge of Pedagogy.” Harvard Educational Review, vol. 64, no.3, 1 September 1994, pp. 278-309, https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.64.3.u27566k67qq70564

Howse, Imogen. “‘Men Are Superior’: Inside the Schools Where Young Boys Idolise Andrew Tate.” NationalWorld, 23 February 2023, www.nationalworld.com/education/andrew-tate-school-boys-idolise-social-media-misogynist-teachers-4037636

James, Will. “Andrew Tate: A Case Study on the Effects of Online Influencers on Students’ Education.” Define the Line, McGill, 20 February 2023, www.mcgill.ca/definetheline/article/andrew-tate-case-study-effects-online-influencers-students-education

Kirsch, Gesa E. “Feminist Critical Pedagogy and Composition.” College English, vol. 57, no. 6, October 1995. pp. 723–29. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/378579.

Musk, Elon [@elonmusk]. “New Twitter policy is freedom of speech, but not freedom of reach…”. Twitter, 18 November 2023, https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1593673339826212864?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1593673339826212864%7Ctwgr%5E127115a27af3f9a2c8737c61ce38bcf6cd3daa72%7Ctwcon%5Es1_&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fmeaww.com%2Fwhy-was-andrew-tate-banned-from-twitter-elon-musk-reinstates-toxic-influencers-account

Radford, Antoinette. “Who is Andrew Tate? The Self-Proclaimed Misogynist Influencer.” BBC News, BBC, 4 August 2023, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-64125045

Tate, Andrew. “Escape the Matrix: By Andrew Tate.” Escape the Matrix (2023). https://www.escapethematrix.money/#price

Tate, Andrew. Hustlers University 4.0, (n.d), https://tateshustlers.com

“Why Critical Feminism?” Teaching Citational Practice, Columbia University Libraries, https://journals.library.columbia.edu/index.php/citationalpractice/whycriticalfeminismournals.library.columbia.edu/index.php/citationalpractice/whycriticalfeminism

Read more at By Melanie Isho.

Articles, Cultural Pedagogy, Education, EssaysRelated News

News Listing

By Rosemary Kasiobi Nwadike ➚

Feminist Miseducation in the Afro-West: Examining (In)Formal Gender Indoctrinations

Articles, Education, Resistance, Social Justice

July 11, 2025

By Joban Sihota ➚

Natural disaster and civic literacy— Language acquisition in the wake of DANA

Articles, Cultural Pedagogy, Education, Public Education

July 8, 2025

By Alexis Andrade ➚

Radical Love: A Revolutionary Force for Liberation

Articles, Cultural Pedagogy, Resistance

June 26, 2025