Recognition of Right – Forty Years after the Rodriguez Case

By Robert Fitzgerald

Introduction

In 1973, a case was decided by the Supreme Court of the United States that has had a profound impact on public education in America. Though unknown by most laypeople today, San Antonio v. Rodriguez was the case upon which future litigation concerning equality of educational opportunity was considered and decided.[1] Essentially, the Court proclaimed that education was not a fundamental right subject to consideration under the equal protection clause. Concerning the inequitable nature of the Texas public school funding scheme, its assertions regarding the fundamental right to education and applicability of the Fourteenth Amendment have been adhered to by many state courts in similar cases surrounding education finance statutes and the opportunities afforded all students. The result has been the maintenance of various state school funding systems characterized by a vastly disparate distribution of resources and opportunities between students.

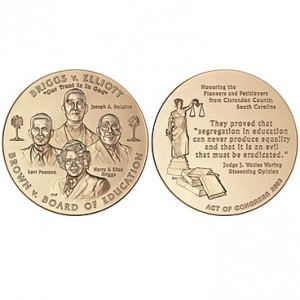

More than forty years later, students across the country are still subject to public school finance schemes as grossly inequitable as those considered constitutional in Rodriguez. Four decades have passed and little has been done to acknowledge the role this case has played in deterring school funding reform and the continued denial of equal educational opportunities for all American children regardless of race or socioeconomic status. The time has come to reconsider Rodriguez and acknowledge it for what it is – an impediment to a promise made twenty years earlier in one of the most recognizable cases of the twentieth century, Brown v. Board of Education.[2]

A Time To Remember

Constitutional historian Michael Klarman suggests that without the Brown decision and the violence that ensued in its wake, many of the changes of the 1960s ushered in through the passage of civil rights legislation would not have occurred as rapidly as they did.[3] It is this legacy that caused scholars, journalists, politicos, and pundits a half-century later to commemorate what many believe to be one of the most important and controversial decisions ever issued. As was stated in one journal at that time, “One would have to have been living under a rock over the past few months not to realize 2004 marks the fiftieth anniversary of the landmark Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education.”[4]

The case that had declared segregation in public education to be unconstitutional received plenty of attention on its golden anniversary, including the creation of a Department of Education commission for the purpose of commemorating its significance and importance in American history.[5] National Public Radio spent the first half of the year exploring the importance of the decision from different angles with various programs intended to retell and highlight some of the more important aspects of the case.[6] According to the ACLU at that time, “This 50th anniversary of Brown is a reminder of our duty to strive for equal educational opportunity for every child in America. It is a reminder of how far we have come – and of how far we still have to go – to improve education, reduce poverty, and ensure a truly diverse society with equal opportunity for all. This ‘joyous daybreak’ must not be allowed to dim.”[7]

Outside of the celebratory rhetoric and response of many, the fifty-year mark also afforded scholars an opportunity to critically assess the case in regards to what was claimed it had potentially resolved. “In short,” Clayborne Carson, director of the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, asserted, “the decision’s virtues and limitations reflect both the achievements and the failures of the efforts made in the last half century to solve America’s racial dilemma and to realize the nation’s egalitarian ideals.”[8] In a speech delivered that year before the American Philosophical Society, William Thaddeus Coleman, Jr., attorney and one of the lead strategists of the case, stated, “(N)o one can say today that racial discrimination or racial segregation has been eliminated completely, or even significantly, in public schools or in public, private, or business life in the United States.”[9] A small sample of the 2004 scholarly output covering Brown in its anniversary year, they exemplify the spirit of many concerning the mythology surrounding the case’s actual influence in American society and education.

Though authors may have differed in their positions regarding the impact of Brown and how it should be commemorated during its golden year, it was commemorated. Like other landmark cases before it, its importance was acknowledged and its principles at least reiterated as a reminder of the direction we were supposed to be headed in regarding equality of educational opportunity.

A Decade Out

Ten years after the commemoration of Brown, another Supreme Court case concerning equality of educational opportunity has passed a decade mark, though without the celebrations, commissions, commemorative ceremonies, or significant output of critical scholarly analysis. In fact, it is accurate to say that the 40th anniversary of San Antonio v. Rodriguez has come and gone with little to no recognition outside of a small cadre of scholars concerned with the lasting effect it had on public schools. Decided in 1973, Rodriguez is neither remembered by most people nor acknowledged with the same critical concern as Brown, a sad fact considering it has likely impacted the contemporary state of public education in America more than those cases that preceded it.

A case concerning the inequitable nature of the Texas school funding scheme, Rodriguez was an attempt by impoverished, minority students and their families to illuminate the vast disparity in fiscal resources between the state’s wealthiest and poorest districts. Aiming to get the funding statute declared unconstitutional under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, the residents of Edgewood, a poor school district with high property taxes and low property values, filed suit five years earlier at the federal district level with hopes of a standard of judicial review that would assess the law in a stringent manner. The increase in the funding disparity that had initially motivated the suit was not enough to convince the Supreme Court that a violation of any constitutional principle had occurred. Where it had seemed to expressly support and enumerate the principle of equality of educational opportunity in Brown, almost two decades later the Court appeared to retract its original position. Forty years later, no one seems to care.

The ruling of the Court in Rodriguez was based on the premise that education, although valuable to the development of every individual, a point iterated by the lower court in this case, was not a fundamental right. This meant that under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Texas school funding scheme would be assessed using a lesser form of judicial review known as the rational basis test rather than strict scrutiny of the law in question. With the less rigorous form of review applied, the Court found a rational relationship between the interests of the state and the education funding statute.

According to the Court, no evidence had been presented concerning the operation of the law and discrimination of a designated suspect class. Also, there was no proof to suggest a direct correlation between poverty and an “absolute deprivation” of educational opportunity.[10] Although it acknowledged the disparity in resources that existed within the Texas school funding scheme, the Court found nothing either discriminatory or irrational concerning its constitutionality. In rejecting the principle of education as a fundamental right of all children, the Court essentially closed the door on future federal cases concerning fiscal resources and equality of educational opportunity.

As a lawyer for the NAACP in the Brown case, Thurgood Marshall had played a pivotal role in getting the Supreme Court to recognize the fundamental importance of education and the equal right of all individuals to it. “Such an opportunity,” Chief Justice Earl Warren enunciated, “where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms.”[11] Almost twenty years later in his Rodriguez dissent, Associate Justice Marshall responded to the Court’s decision concerning the Texas statutory funding scheme in a critical manner. According to Marshall, “(T)he majority’s holding can only be seen as a retreat from our historic commitment to equality of educational opportunity and as unsupportable acquiescence in a system which deprives children in their earliest years of the chance to reach their full potential as citizens.”[12] The principles of fundamental right and equality of opportunity which had been enumerated by the Court in Brown were expeditiously wiped out by Rodriguez. Forty years later, students attending schools in impoverished communities are continuing to be subjected to an education far inferior to that of their more wealthy counterparts.

So why as this fortieth year has recently concluded should we reflectively consider and challenge the decision of the Court in Rodriguez? The answer is threefold. First, as a democratic society it is imperative that we recognize the importance of education for the development of every individual and the wellbeing of the community as a whole. As Thomas Jefferson bluntly stated, “If a nation expects to be ignorant and free, in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be.”[13] If the basic principles of democracy are to be passed down to future generations, it will be through a system of public schools where the principle of equality of opportunity is not only promoted, it is practiced and protected. The United States of America is one of only a handful of countries in the world that does not recognize education as a fundamental right of all, a principle that the United Nations has enumerated in its Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This is an absurdity considering the historical commitment to public education in this country and the role it has traditionally played in its development.[14]

Second, since the Rodriguez decision, the disparity in fiscal resources available to schools has grossly increased in numerous states, prompting a number of cases where local courts have simply adhered to the decision of the federal Court on this issue. An example of this is in Illinois where in 1996 the state supreme court affirmed the funding scheme in the case Committee v. Edgar.[15] Similar to Rodriguez, the court in this case rejected the principle of fundamental right due to a lack of expressed inclusion in the wording of the education article of the Illinois Constitution. Although the court described the system as “unwise, undesirable or unenlightened from the standpoint of contemporary notions of social justice,” its constitutionality was unquestionable.[16] Today, Illinois students living in impoverished communities with low property values suffer significantly under a funding system that has been described by the Education Law Center as “low-effort” and “regressive.”[17] Rated 49th in disparity between the richest and poorest school districts, it has perpetually received a grade of “F” for funding fairness.[18] Not alone, Illinois is just one of many states where local litigation has adhered to the position taken in Rodriguez on the right to education and equality of opportunity.

Third, in light of the recent trend in education towards an increased emphasis on standardization of curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment, it is paramount to consider the impact of the Rodriguez decision on the opportunities schools are providing their students. Essentially, if standardization is going to be the forced model under which education must operate, the least that can be done is to make the opportunities available to all students equal regardless of the property values of the communities in which they live. Although a more critical, compassionate, and utopian outlook for education would be the total elimination of such practices, it does not appear they will be eradicated anytime in the near future. Therefore, while subjected to such oppressive policies it is critical to challenge the decision of the Court concerning the principle of fundamental right. If the right to education was recognized, those opportunities made available to students in communities with limited resources could more strictly be scrutinized. This would re-open the door for litigation to be enacted against states where resources are inequitably distributed yet all districts are expected to adhere to laws concerning the adoption of standards, performance on standardized tests, and teacher accountability.

To more simply state the above three propositions, it is ridiculous to consider that in the United States of America education is not recognized as a fundamental right of all children despite the fact that in the last decade there has been an increase in legislation at both the federal and state levels concerning teaching and learning. Under federal initiatives such as No Child Left Behind, Race to the Top, and the adoption of Common Core Standards in numerous states, schools are continuously being asked to do more with less. All the while those who began the decade with limited resources are facing greater pressures than ever before. Maybe in a decade, upon its golden anniversary, there will be greater attention paid to the Rodriguez decision and the impact it has had on public schooling in America. Considering all the attention Brown garnered in its fiftieth year, one can only hope this will happen and potentially rekindle a much needed discussion concerning equality of educational opportunity.

[1] San Antonio v. Rodriguez, 36 L. Ed. 2d 16 (US Supreme Court 1973) 16-105.

[2] Brown v. Board of Education, 98 L. Ed. 873 (US Supreme Court 1954) 873-882.

[3] Michael Klarman, Brown v. Board of Education and the Civil Rights Movement (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 126.

[4] “How America’s Newspapers Responded a Half-Century Ago to the Supreme Court’s Ruling in Brown v. Board of Education,” The Journal of Black in Higher Education No. 45 (2004): 46.

[5] “Brown v. Board of Education 50th Anniversary Commission.” accessed March 5, 2014, http://www2.ed.gov/about/bdscomm/list/brownvboard50th/index.html.

[6] “Looking Back: Brown v. Board of Education.” http://www.npr.org/news/specials/brown50/. Accessed March 5, 2014.

[7] “50 Years Later: Brown v. Board of Education.” https://www.aclu.org/racial-justice/50-years-later-brown-v-board-education. May 17, 2004.

[8] Clayborne Carson, “Two Cheers for Brown v. Board of Education,” The Journal of American History 91, No. 1 (2004): 26.

[9] William Thaddeus Coleman, Jr. “Truths That Unfortunately Were Not, and Still Are Not, Sufficiently Self-Evident,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 148, no. 1 (2004): 447.

[10] Rodriguez, 37.

[11] Brown, 880.

[12] Rodriguez, 65.

[13] Thomas Jefferson to Colonel Charles Yancey, 6 January 1816, http://www.constitution.org/tj/jeff14.txt.

[14] For more on this theme see Why We Still Need Public Schools: Public Education for the Common Good. (Washington, DC: Center on Education Policy, 2007).

[15] Committee v. Edgar, 672 N.E. 2d 1178. (Supreme Court of IL 1996) 1178-1207.

[16] Ibid., 1196.

[17] Bruce D. Baker et al, Is School Funding Fair? A National Report Card (Newark, NJ: Education Law Center, 2012).

[18] Ibid.

Related News

News Listing

By Rosemary Kasiobi Nwadike ➚

Feminist Miseducation in the Afro-West: Examining (In)Formal Gender Indoctrinations

Articles, Education, Resistance, Social Justice

July 11, 2025

By Joban Sihota ➚

Natural disaster and civic literacy— Language acquisition in the wake of DANA

Articles, Cultural Pedagogy, Education, Public Education

July 8, 2025