Seeing Ourselves in Public: Representation, Relation, and Political Agency in Cultural Spaces

This paper is the revised version of a graduate term paper, adapted for publication under the Public Intellectuals Project.

Born out of student-driven reforms in British adult education, Cultural Studies is characterized by a resistance to institutional norms and disciplinary constraints. It aims to bring the abstract work of theoretical analysis “down” to the dealings of everyday life. The main goal for cultural theorists is to understand how power works within culture, in all its forms and namings – alternative, mainstream, underground, popular.[i] This essay looks beyond the academy as a place to do this work, speaking to the potential of the museum and public art gallery as powerful sites for cultural analysis and critical pedagogy.

It’s true that these are institutions established upon the colonial project of collecting, exhibiting, and educating,[ii] with some spaces continuing to attract audiences of select social and cultural classes.[iii] But contemporary operations in museums and art galleries can still cultivate progressive and inclusive sensitivities, whether in the objects they exhibit, their interpretative methods, and public programming. In what follows, I’ll specifically address the contents of museum and gallery exhibitions – that is, I’ll be discussing what is placed for show in these spaces, as well as the decision-making involved in making these displays, as inspired by a recent visit to the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) in Toronto, Canada. The goal is to demonstrate how museums and public art galleries can nurture political agency, by embodying the conditions required for its enactment. Drawing upon Henry Giroux’s work on critical pedagogy, I first speak to the idea of political agency as fundamentally grounded in our relations to others. Without an interest in the other, there can be no basis for working towards a collective social betterment. Taking select curatorial interventions from Faith and Fortune: Art Across the Global Spanish Empire, namely, the inclusion of Philippine artifacts, contributions from local community members, and the use of Tagalog didactics, I then examine how museums and public art galleries can enact methods of critical pedagogy. When these institutions present narratives that are relevant to and reflective of their local communities, they make it possible for visitors to personally identify with public displays and, hopefully, situate themselves in relation to their sociopolitical locale. That is, they make it easier for visitors to imagine their lives as in relation with others.

Contemporary curatorial practice, however, has both its opportunities and pitfalls, and progressive approaches to the public display of art, history, and culture is far from guaranteed in these spaces. Any meaningful cultural practice requires reflexivity, and in the public sector, this must be a publicly engaged one. If these institutions aspire to be spaces where people can learn to exist in relation to one another, then they must also be in constant conversation with communities, ultimately seeing themselves as part of – and not separate or removed from – their own locale.

Political agency as a prerequisite for critical pedagogy

As a core element of democratic civic society, political agency cannot be realized without an interest in the Other. The global rise of neoliberal ideology has valorized a particularly solitary notion of the individual- he who does it all on his own, he who enjoys his successes and manages his misfortunes, which in turn come about by his own hand, decisions, merits, and shortcomings. Giroux describes this view of the self as an “insidious individualism…reinforced by the notion that all problems, however systemic, are a matter of personal responsibility and the result of individual failures”.[iv]

The notion of political agency, on the other hand, locates the influence of free will and action within the public sphere, understanding that the individual is always situated in a broader context. The individual’s existence is shaped by relations to others that are inherently asymmetrical, and these relations exist on different scales, from the local to the national as well as the global. Acknowledging this essential connectivity presupposes a view of the self that exists “beyond the regressive neoliberal notions of raw self-interest, regressive notions of individualism, and commodified conceptions of personal happiness.”[v] Exercising one’s capacity to take part in the public sphere is a form of “reclaiming a democratic notion of the social,”[vi] or in other words, reigniting an interest in the other.

How, then, to cultivate a sense of political agency? I’ve been thinking about the phrase “conditions of political agency,” which regularly appears in Giroux’s Pedagogy of Resistance. Such language implies that agency itself is situated – it must be enacted somewhere, the subject who enacts it always exists in a place. Individuals do not become socially conscious in a vacuum; their sensitivities and awakenings to issues outside of themselves are contextually grounded in space, whether this is as narrowly defined as one’s graduate cohort, or as broadly based as a sense of national belonging. The work towards social change is necessarily collective, and as such, there must be a deliberate “working towards” community. Addressing the conditions for political agency therefore includes addressing the habits, practices, and attitudes that reflect an interest in and care for one another.

Cultural narratives in the museum and public art gallery

Museums and public art galleries are not only sites for (re)igniting a sense of social situatedness; they are key areas for observing the processes that assign differing values across culture. As archives, they have a certain authority in cementing a public canon, or what is considered to be the “official” cultural and historical narrative. Curatorial work involves the assemblage of disparate objects to express a narrative, and these narratives possess ideologies and valuations of their own. It is through this lens of visual art and material culture that the museum and public art gallery can be places of rich analysis, of examining the “practices used…to categorize, distill and essentialise the world.”[vii]

In Pedagogy of Resistance, Giroux names cultural institutions as spaces capable of creating “the ideas, narratives, and pedagogical relations necessary for connecting the shaping of individual and collective consciousness.”[viii] Such a critical pedagogy, as he describes it, rejects standardized educational materials and calls for methods of teaching that specifically foreground the different subjectivities in any given classroom.[ix] In the context of the arts institution, this can look like what Aaliyah El-Amin and Correna Cohen describe as positive representation, which can help marginalized individuals “see themselves [included in the institution], recognize themselves as artists, and learn to push back productively against barriers to their unquestioned belonging.”[x] The emphasis is not merely on institutional inclusion, but the opportunity to see oneself in broader historical, societal, and political narratives. These efforts foster a sense of “being with” others in community. Of course, the degree to which visitors identify with public narratives will undoubtedly vary, and positive reception is never guaranteed, but in becoming “visible to themselves and to each other,”[xi] the hope is that a recognition of difference and the negotiation of multiple identities becomes part of the practice of situating oneself in relation to the other.

Seeing oneself in public spaces, imagining oneself anew: Contextualized narratives in Faith and Fortune: Art Across the Global Spanish Empire

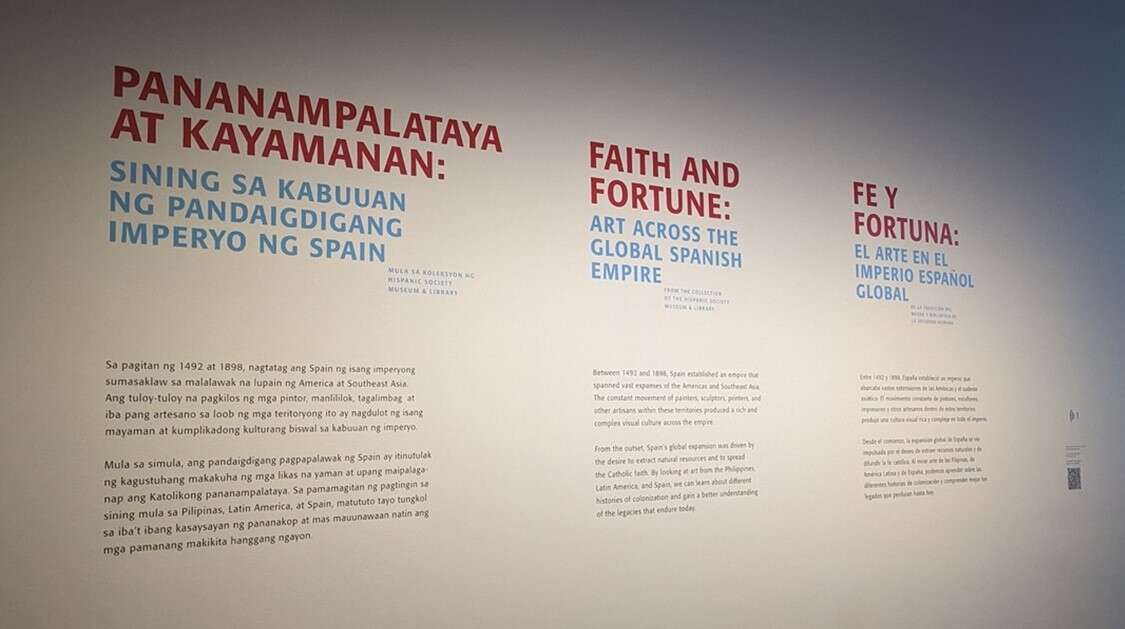

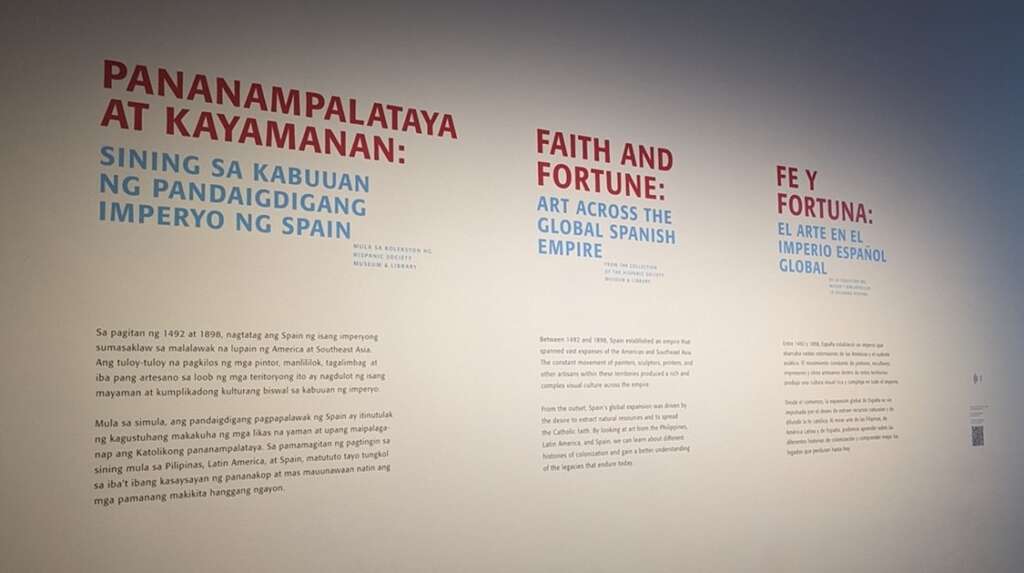

Featuring paintings, textiles, ceramics, sculpture, and daguerrotypes from Latin America and the Philippines, Faith and Fortune: Art Across the Global Spanish Empire examined the scope of Spanish colonization through the material culture that arose from imperial conquest and trade. While the exhibition centers on colonial activity, there are several curatorial interventions that make an effort to refract what might be seen as “yet another” exhibit of European history, from the inclusion of Filipinx and Latinx community members in interpretive materials, to the use of multilingual didactics in the gallery space.

The sixth track of the exhibition audio guide features professor, dancer, and filmmaker Russ Patrick Alcedo. He speaks to the display of the Santo Niño, a religious image of Jesus Christ commonly found in Catholic Filipino homes. Alcedo’s commentary goes beyond the make and origins of the artefact – such information is already provided on the exhibit labels. Instead, he supplements the didactics with personal anecdote:

I’ve always felt at home with Santo Niño…I find his gender ambiguity to be reassuring. Like the Santo Niño, I gave myself the freedom to not follow my society’s received understanding of what kind of gender identity I needed to embody and practice while growing up. I have taken ownership of the way in which I practice Roman Catholicism, as an individual who is non-conforming and creative in my own interpretation of what it means to be a Catholic and to participate in the legacies of the Spanish Empire.[xii]

In the audio guide, visitors learn that Alcedo hails from Panay, a region of the Philippines that celebrates Ati-Atihan, a festival that honours the Santo Niño. His closing statements tie his personal relationship to Santo Niño with the geopolitical processes that introduced the artefact to the Philippines in the first place, speaking to the ways cultural ritual can reproduce and renegotiate narratives on a communal level: “The way we celebrate Ati-Atihan is a window into our ability to Filipinize the foreign, to Filipinize Catholicism, and the Spanish Empire that brought this faith to us.”[xiii]

I draw attention to Alcedo’s commentary as an example of a critical curatorial intervention that considers the relationships individuals might have with objects on show at exhibitions. While this curatorial decision is a far cry from speaking to the contested histories behind the displayed objects, and the enduring colonial project of museum display, it is perhaps more generative than purely critical: the reflections from community members with relationships to the histories in Faith and Fortune can be invitations for the public to ponder their own histories in relation to the exhibition. They are examples of how the personal can be situated within broader historical and political contexts, with the illustrative help of public exhibitions.

Being able to identify with art and artefact in public space provides avenues to imagine oneself anew, and in this case, in relation to others. Shawn Rowe, James Wertsch, and Tatyana Y. Kosyaeva write of museums as spaces where “personal, private or autobiographical narratives come into contact with larger-scale, collective or national narratives,” for “the creation of imagined communities.”[xiv] The act of imagining other ways of being can be deeply generative for social change. Max Haiven & Alex Khasnabish describe the radical imagination as a dynamic process that is practiced together, in which the enacting the imagination as a “shared landscape”[xv] is more effective for social transformation than only thinking of the imagination as a function of the solitary dreamscape. Social media may romanticize the museum and gallery as a place of lone excursion, where one meditates on art and artefact in hushed, intimate space, but I want to emphasize the potential that these spaces have for encouraging imaginaries of “social reflexivity,” rather than “individual endeavour.”[xvi] Being able to connect one’s personal histories to historical artefacts involves a recognition of the ways one’s life is fundamentally shaped by broader relations. Alcedo’s reflection illustrates this connectivity; we hear this as he ties his relationship to the Santo Niño to Spanish colonization and its role in shaping Philippine ceremony and gender norms. When cultural institutions lay the foundations for these connections, it becomes much easier to fathom how power shapes one’s relationships to the world at large, and why these questions of power matter to an individual in the first place.

The highs and lows of representation: Multilingual didactics in Faith and Fortune

Institutional efforts in critical pedagogy require a careful identification of a target audience and therefore a demonstrated effort to understand and learn from these communities. A major exhibition in a city known for its multiculturalism, Faith and Fortune is a distinct opportunity for Filipinx and Latinx to see aspects of their material culture celebrated in public display. As a Filipina myself, I was eager for its opening, and I earmarked the show as a must-see for my next visit to Toronto. Receptions to cultural exhibitions are nuanced, however, and as my own encounter with the multilingual didactics in the gallery space will show, the dynamics of public representation is complex and requires continuous dialogue and institutional reflection.

Bold introductory wall text in Tagalog, English, and Spanish greet the visitor upon entrance to the show. I was immediately delighted, and as I moved through the exhibit to a section on Philippine daguerreotypes, eventually moved to the point of tears at the sight of Tagalog in such a central cultural space in the city.

Introductory wall texts in Tagalog, English, and Spanish for Faith and Fortune. Author’s own image, 2022.

A block of Tagalog text was a particularly novel sight for me, since my diasporic engagement with the language has mostly involved a vernacular interspersed with English and Spanish. It took me several minutes to make it through the opening didactics, stumbling on unfamiliar vocabulary along the way. I attributed these difficulties to a personal lack of comprehension, as someone whose Tagalog capabilities revolve around its spoken form – my social relations, my consumption of Philippine music, film, and television. These stumbling blocks didn’t dampen much in the moment, however, and I left the AGO excited for future relationships between Toronto’s arts institutions and Philippine artists and researchers. Contested as museum practice may be, there was something uplifting about seeing one’s cultural narratives spotlighted in public space. This was only amplified with the knowledge that, to some degree, Filipinx were involved in shaping the way these stories were told.

Still, the question of the opaque didactics remained, however. In my excitement to share the news about Faith and Fortune, I asked my parents to translate the labels I had photographed. As native Tagalog users, they found the texts generally difficult to understand. Even the first few words in the entrance texts – manlililok, tagalimbat – were unfamiliar for them. After finding their English counterparts- sculptor, printer- it became clear that the issue was not simply a matter of academic or artistic jargon, but rather that English or Spanish loanwords were more commonly used in the vernacular. They agreed that the text was awkward to read, and I wondered if this was the result of direct translations, or attempts to keep the text close as possible to “pure” Tagalog expression. I wondered then if our experience with the didactics was not a singular one – if the vocabulary would also be inaccessible to other Filipinx who use Tagalog in its hybridized vernacular, or another dialect entirely.

Tagalog didactics for the display of daguerreotypes of a colonial-era Philippines. Author’s own image, 2022.

My goal is not to make a linguistic study from anecdote, but rather to speak to the highs and lows of curatorial practices that attempt to engage with broader audiences. As the initial reaction to my visit demonstrated, it can be invaluable to see one’s own narratives reflected in institutional spaces, especially if they are spaces like museums and public art galleries, which possess immense cultural authority and influence in establishing a historical canon. However, the integration of representation and community is never a straightforward process. There are curatorial interventions in Faith and Fortune, like the audio guide contributions from individuals with personal ties to the exhibition artefacts, that suggest a sensitivity to the communities involved. It is here that an understanding of power in cultural spaces (especially ones that aim to educate and/or celebrate) can be helpful in navigating the complexities of representation, given its demand for specific, close, and contextualized methods of engagement. Building knowledge with an intended audience can help cultural institutions form meaningful relationships with the very same communities they claim to invite into these public spaces.

Like many public institutions, museums and art galleries do not often live up to such critical standards. They can be insular and conservative spaces, especially if they see their institutional mission as one of preservation. Bernadette Lynch summarizes the issue as an “‘us’ and ‘them’ relationship”[xvii] where the museum positions itself as separate from its local community. Efforts to co-create or co-curate with the public are “thus often unmasked as a shallow political gesture,” lack “authentic decision-making power,” and fail to “[place] people at the centre, as active agents in their own right,” thereby denying the public “their active agency and the necessary possibility of resistance.”[xviii] To be meaningful spaces for an active and engaged public, the museum and public art gallery must see themselves as part of the community. They are not only product and producer of public narratives, but product and producer of the public itself, “less of a separate entity and more of an emanation of communities.”[xix] If these spaces aim to encourage personal reflexivity for their visitors, then an equal degree of internal reflexivity is required. Lynch suggests a “collaborative critical analysis” that illuminates “how knowledge, identities, and authority are constructed within particular sets of social relations, including those of the museum itself.”[xx] As Darlene Clover & Kathy Sanford insist in their study of pedagogy in contemporary museum space: “critical institutional reflection…does not make the mansion and colonialism ‘go away’, but it disrupts its power and plants the seeds of epistemological change.”[xxi]

“We don’t need master narratives…We need relational narratives that bring together different struggles for emancipation and social equality.”[xxii]

This paper was driven by a search for places where Cultural Studies and critical pedagogy might occur outside the university, a search for ways to do the work beyond the institution’s disciplinary conjectures.[xxiii] Lawrence Grossberg writes that Cultural Studies requires a “double articulation, which must always be located in the specific historical conjecture and institutional context in which the articulations are both enabled and constrained.”[xxiv] Museums and galleries are well positioned for such a mission because, aside from their display of art and artefact, they can easily demonstrate how public narrative is constructed, not least by their own interpretative efforts. The question of politics and art is better reserved for a different essay entirely, but in this one I have tried to argue that the spaces in which our material cultures are displayed are themselves important areas for cultivating a socially conscious citizenry. They speak to a fundamental element of political agency: understanding one’s existence in relation to others. Without recognizing one’s place in broader social, political, and historical contexts, then it is impossible to fathom questions of power, which are fundamentally questions of relation. Careful curation and meaningful representation can make museums and public art galleries places for visitors to see themselves reflected in public cultural narratives, a core tenet of critical pedagogy.[xxv]

This is not to say that museums and public art galleries have a rightful authority over the historical or cultural canon. The ability to imagine oneself in the context of a wider community is also a prerequisite to responding to public narratives, and this includes their possible negotiations, re-creations, or rejection. Though this essay looked at curatorial practice, is worth noting that education and programming are even more expansive areas for critical pedagogy. Museum educators have a direct influence on programming that encourages critical cultural literacy,[xxvi] providing not only opportunities for reflection in exhibitions but the tools for cultural analysis.

There is no single exhibit, show, or equity & diversity policy that can transform the museum and public art gallery into an exemplary space of cultural and political engagement. Creating spaces for public reimagination is a slow process, in the same way that learning to ‘see’ art or ‘read’ an exhibit requires building new habits of looking. Haiven & Khasnabish’s notion of social change emphasizes this “transformation of temporality,” requiring a shift in “our sense of who and what is worthy of our time…what we imagine to be critical to struggle and what we imagine to be a distraction.”[xxvii] The public work of arts institutions requires the same discretion and active social reflection. In her essays on place, art, cultural production, Carol Becker calls for “a cultural investment in understanding how art emerges from and permeates people’s daily lives in order to know what the future of museums could be.”[xxviii] This sentiment can also be reversed: art and artefact are witness to our fundamental relationality. We can’t know for certain what our social future will be, but if we are able to recognize ourselves as part of collectives, part of narratives larger than our own, it becomes much easier to imagine futures where we exist considerate of and in collaboration with one another.

[i] My foundational understandings of the field are in part informed by the writings of Lawrence Grossberg’s “Bringing It All Back Home: pedagogy and cultural studies,” and “Cultural Studies: What’s in a Name?” In Bringing It All Back Home: Essays on Cultural Studies, Duke University Press, 1997; Richard Johnson’s “What is Cultural Studies Anyway?” Social Text, 6(1), 38-80, 1986; and Raymond Williams’ “The Future of Cultural Studies,” in John Storey’s What is cultural studies?: A Reader, Arnold, 1996.

[ii] Lynch, B. “Good for You, But I Don’t Care!: Critical Museum Pedagogy in Educational and Curatorial Practice,” Contemporary Curating and Museum Education 14 (2016), pp. 255–268, transcript Verlag.

[iii] Becker, C. “Museums and the Neutralization of Culture: A Response to Adorno.” In Thinking in Place, 39–62, Routledge, 2016.

[iv] Giroux, H. Pedagogy of Resistance: Against Manufactured Ignorance. Bloomsbury Academic, 2022, 23.

[v] Giroux, H. Pedagogy of Resistance, 202.

[vi] Giroux, H. Pedagogy of Resistance, 202.

[vii] Clover, D., and Sanford, K. “Contemporary museums as pedagogic contact zones: Potentials of critical cultural adult education,” in Studies in the Education of Adults, 48(2), 2016, 136.

[viii] Giroux, H. Pedagogy of Resistance, 201.

[ix] Giroux, H., and Christopher G. Robbins. (2006). “Doing Cultural Studies: Youth and the Challenge of Pedagogy,” In Giroux Reader, Routledge, 2006, pp. 117–50.

[x] El-Amin, A., & Cohen, C. “Just Representations: Using Critical Pedagogy in Art Museums to Foster Student Belonging,” Art Education (Reston), 71(1), 2011, 11.

[xi] Worth, F. “Postmodern Pedagogy in the Multicultural Classroom: For Inappropriate Teachers and Imperfect Spectators,” Cultural Critique, vol. 25, no. 25, 1993, pp. 5–32, quoted in Giroux Reader, 293.

[xii] Alcedo, P. R., & Art Gallery of Ontario. “Faith and Fortune – 16 Catholicism in the Philippines,” In Faith and Fortune: Art Across the Global Spanish Empire Audio Exhibition Guide, 2022, https://soundcloud.com/agotoronto/16-faithandfortune-audioguide

[xiii] Alcedo, P. R., & Art Gallery of Ontario. “Faith and Fortune – 16 Catholicism in the Philippines.”

[xiv] Rowe, Shawn M., James V. Wertsch, and Tatyana Y. Kosyaeva. “Linking Little Narratives to Big Ones: Narrative and Public Memory in History Museums.” Culture & Psychology 8, no. 1, 2002, 97.

[xv] Khasnabish, A, and Max Haiven. The Radical Imagination: Social Movement Research in the Age of Austerity. NBN International, 2016, 226.

[xvi] Murray, M. “Reflexive Learning for Active Citizenship,” in Reflexivity and Critical Pedagogy. eds. Ryan, Anne, and Tony Walsh. Boston: BRILL, 2018, 116.

[xvii] Lynch, B. “Good for You, But I Don’t Care!: Critical Museum Pedagogy in Educational and Curatorial Practice,” 256.

[xviii] Lynch, 256.

[xix] Lynch, 262.

[xx] Lynch, 267.

[xxi] Clover and Sanford, 137.

[xxii] Giroux, H. Pedagogy of Resistance, 172.

[xxiii] Hall, S. “Cultural Studies and its Theoretical Legacies.” in Chen, Hall, S., & Morley, D. Stuart Hall: Critical dialogues in Cultural Studies. Routledge, 1996; Grossberg, L. “Cultural Studies: What’s in a Name?” In Bringing It All Back Home: Essays on Cultural Studies, Duke University Press, 1997

[xxiv] Grossberg, L. “Bringing It All Back Home: pedagogy and cultural studies,” in Bringing It All Back Home: Essays on Cultural Studies, Duke University Press, 1997, 384.

[xxv] Giroux, H., and Christopher G. Robbins. (2006). “Doing Cultural Studies: Youth and the Challenge of Pedagogy,” In Giroux Reader, Routledge, 2006, pp. 117–50.

[xxvi] El-Amin, A., & Cohen, C. “Just Representations: Using Critical Pedagogy in Art Museums to Foster Student Belonging,” Art Education (Reston), 71(1), 2011.

[xxvii] Khasnabish, A, and Max Haiven. The Radical Imagination, 192.

[xxviii] Becker, C. “Museums and the Neutralization of Culture,” 51.

Read more at By Issra Marie Martin.

Cultural Pedagogy, Essays, ResistanceRelated News

News Listing

By Maya Phillips ➚

Failure to Reeducate: Perpetuations of Cultural Fascism in Post-War Germany

Articles, Cultural Pedagogy, Public Pedagogy

February 9, 2026

By Rosemary Kasiobi Nwadike ➚

Feminist Miseducation in the Afro-West: Examining (In)Formal Gender Indoctrinations

Articles, Education, Resistance, Social Justice

July 11, 2025