Aesthetics of Rebellion: Normative Feminine and Masculine Visuals in a Christian Nationalist Context

In a global culture marked by both increasing fascistic beliefs and pervasive internet use, it’s easy to draw a connection between the two. As a tool for the dissemination of information–or disinformation–the internet is unprecedented, and those attempting to promulgate particular ideologies have taken full advantage. Numerous reactionary movements in particular–including men’s rights activists, TERFs, and white supremacists–have made use of the internet as a multimedia experience to recruit and radicalize users. I would like to examine, in particular, Christian far-right nationalist usage of the internet as a recruiting tool via what I would describe as “the aesthetics of rebellion”. (As a note, I will be using the terms “Christian far-right nationalist”, “Christofascist”, “conservative Christian” and “Christian fundamentalist” as well as any derivations thereof interchangeably for the purposes of this paper, so as to cover as many nuances in the demographic as possible.) We might also describe this as “the myth of rebellion”, as the particular brand of “rebellion” that the Christian far-right is positing is, at its core, deeply regressive and conformist. Christian nationalist movements online employ these aesthetics of rebellion in two opposite but ideologically coupled ways: through the systems of normative femininity and normative masculinity. By suggesting that traditionalist, conservative presentations of femininity and masculinity are in some way “rebellious”, Christian fundamentalists are hoping to entice and ultimately recruit younger internet users who desire to inhabit a countercultural identity. Simultaneously, these younger internet users also feel a need to express themselves via the internet as an aesthetic medium that confers cultural capital. These desires are commonly expressed by this demographic, and far-right Christian groups, like many other reactionary online movements, have learned how to harness them to advance their fascistic agendas.

To understand what is meant by “rebellious” in a Christofascist context, it is illuminating to examine what Umberto Eco, in his 1995 essay “Ur-Fascism”, describes as a resistance to “modern depravity” (Eco 6). Eco suggests that fascism is founded upon the “cult of traditionalism” (6) and that “traditionalism implies the rejection of modernism” (6). As “modernism” could be described as one of the foundational tenets of our social formation, fascist traditionalism can thus posit itself as being in direct opposition to what we might describe as “mainstream culture”. Thus, despite embodying conservative ideologies–typically the opposite of what we imagine when thinking of “rebellion”–as long as fascist movements claim to be fighting mainstream modernity, they can position themselves as “countercultural” and therefore marginalized.

With this understanding, we can then turn our attention to the first half of the formula for “rebellious” conservative Christian aesthetics: traditional femininity. What is meant by “traditional femininity” here is, broadly speaking, implicitly understood to mean not only normatively feminine expressions of identity and behaviour, but also a femininity that is white, cisgender, able-bodied and heterosexual. A number of Christian nationalist online influencers suggest that the aesthetics of so-called traditional femininity are “rebellious”; though we’ve established that these aesthetics are patriarchal, hetero- and cisnormative and white supremacist–regressive, in other words–influencers are nevertheless able to use the language of rebellion, alienation or individualism to give them a countercultural appeal.

To delve further into this, I’d like to take a look at a particular pair of online Christian fundamentalist influencers, Bethany Beal and Kristen Clark, co-owners of the Evangelical Christian blog “Girl Defined”. As the name of their blog suggests, Beal and Clark are attempting to quite literally “define”–or redefine–womanhood (or girlhood, if you prefer, a term with some infantilizing connotations). Their definition of womanhood is positioned in direct opposition to “modern” secular womanhood. Indeed, the titles found in their first book are, in and of themselves, illuminating: the book is entitled Girl Defined: God’s Radical Design for Beauty, Femininity and Identity, with the use of the word “radical” suggesting not only something essential and ingrained but also revolutionary. The first chapter of their book is titled “Femininity Gone Wrong” (Beal and Clark, Girl 9), implying that modern, mainstream femininity–what they purport to be rebelling against–has at some point taken a wrong turn or degenerated. The way they describe it is thus: “the sensual women on magazine covers. The perfect hair on shampoo commercials. The bone-thin models on mall posters […] the prevailing secular culture enticed us with its version of femininity” (13). Additionally, in offering why they wrote their book, the authors claim that they are recommending “something better. Something you won’t find in the culture. We’re here to throw the flag on modern femininity and say, ‘Enough is enough.’” (15) The subtext here is clear: Beal and Clark are setting up a critique of modern femininity that emphasizes sexual objectification, thinness and physical perfection. They are offering what seems on the surface to be a salve for the sting of capitalistic, misogynistic expectations of women–expectations that revolve around a woman’s looks–by bringing up typical loci of women’s insecurities (and what, in other contexts, would be common feminist talking points). In other words, they are positioning their ideology as being countercultural, and in fact refer to women who don’t adhere to Biblical womanhood as “culture-defined girls” (22). They go on to indicate that “although many people consider [pushing for gender neutrality] extreme, it’s slowly gaining mainstream popularity” (49) and that “our culture’s modern view on gender permeates almost every TV show, movie, song, magazine and book” (49)–in other words, that Biblically-ordained womanhood is in direct opposition to our mainstream culture. At one point, Clark even says that pushing against what she refers to as “modern [women’s] independence” (33) is like “paddl[ing] against the current” (33), a metaphor for rebellion if ever there was one.

Where, then, do aesthetics fit into this? As I have already suggested, Beal and Clark are critiquing not only what they consider to be the ideologies of modern womanhood, but also the aforementioned capitalistic, aesthetic trappings of femininity. But their offerings, rather than removing aesthetics from the equation, instead double down on them, merely bringing a different set of aesthetics to the fore and reinforcing normative beauty standards. Again, Girl Defined’s chapter titles can provide us with some immediate insight into Beal and Clark’s tactics: consider the title of chapter 6, “Modern Chic, Meet Biblical Womanhood” (60). Despite their earlier critique of the appearance-based pressures modern women experience, the two are still preoccupied with being “chic”–and, much more importantly, assume that their target audience (that is to say, young women) will be too. After some cursory lip-service to inner beauty–they suggest that “being drop-dead gorgeous on the outside can’t bring a woman lasting fulfillment and security on the inside” (89), again a sentiment not out of place in Feminism 101 discourse, they go on to extol the virtues of being normatively feminine. “We (Kristen and Bethany) enjoy dressing fashionable and feminine” (89), they say. “We both enjoy doing our hair and makeup on a regular basis. We like enhancing the natural facial features God has given us. We like exploring new products to see what works and what doesn’t.” (89) This is further reinforced in a pamphlet available on their website titled Project Modesty: How to Honor God with Your Wardrobe While Looking Totally Adorable in the Process, where they state that “you were born to be feminine and breathtakingly beautiful” (Beal and Clark, Project 10) and that “modesty and fashion can go hand-in-hand. Yes, you can look adorable and still stay covered” (12). Near the end of the book, they offer a list of clothing stores where they like to shop, further underscoring the link between their vision of Biblical womanhood and normative beauty standards (109). After repeatedly reinforcing that dressing modestly is “rebellious” and “countercultural”, they then emphasize that it is nevertheless also “fashionable” and desirable to perform femininity to a particular rigid set of standards.

The fundamental counterpart to the aesthetics of normative femininity is, of course, that of normative masculinity. While the two paradigms operate under very different conditions, the two are nevertheless both crucial parts of the equation, with one reinforcing the other. Within the context of Christian nationalism, “traditional masculinity”, as with its counterpart, is also inherently patriarchal, white supremacist and hetero- and cisnormative. Despite again being emblematic of repressive and regressive social norms, the Christian far-right has nevertheless found a way to frame traditionally masculine aesthetics as “rebellious” or “countercultural”. In particular, I wanted to discuss the intersection of aesthetics with the insurrection at the Capitol on January 6th, and the ways in which particular images have been deployed in service of far-right ideologies.

Perhaps the most memetic of images from January 6th are those of Jacob Chansley, popularly known online as “the QAnon Shaman”. On January 6th, Chansley showed up at the Capitol with his face painted red, white and blue, dressed in only pants and a raccoon-fur, horned hat, and carrying a spear with an American flag zip-tied to the tip. The appeal to the “cult of traditionalism” is evident, but in a manifestly different way than is suggested by ideals of Biblical womanhood: Chansley and his supporters are, instead, appealing to a sense of pre-Enlightenment, almost primal masculinity. As Umberto Eco suggests when describing “modern depravity”, fascists often think of “The Enlightenment, the Age of Reason […] as the beginning” (Eco 6); lionizing this particular image of masculinity is part and parcel of this ideology. That Chansley’s persona contains not only the aesthetics of American nationalism but also those of the stereotyped primeval Nordic “shaman” is also no coincidence: Eco notes that fascistic ideologies are “syncretistic [and] whenever they seem to say different or incompatible things it is only because all are alluding, allegorically, to the same primeval truth” (6), concluding that, for fascists,“truth has been already spelled out once and for all, and we can only keep interpreting its obscure message” (6). He additionally points out that “the Nazi gnosis was nourished by traditionalist, syncretistic, occult elements” (6). Chansley himself has gone on record espousing beliefs that recall Eco’s sentiment on fascist occult beliefs, saying of present-day US politics that “in order to beat this evil occultic force you need a light occultic force… [you need] a force that is of the side of God, of love… almost like on the side of the angels… as opposed to the demons” (Crossley 2021). It is also worth noting that in addition to the elements described above, Chansley has numerous tattoos of Norse pagan symbols that have been co-opted by white supremacist groups, such as Thor’s hammer and the Valknut. (Birkett 2021) Eco also notes that notions of fascistic masculinity are tied to an obsession with war and conflict–he observes that fascist groups are “hierarchically organized (according to a military model)” (Eco 8) and that “the Ur-Fascist hero tends to play with weapons—doing so becomes an ersatz phallic exercise” (8). All of this, combined in Chansley’s January 6th garb, provides not only a powerful vision of traditionalist gladiatorial masculinity, but also of rebellion. Though it was not the only time he wore it, by far the most disseminated images of Chansley in his “QAnon Shaman” garb were taken at the Capitol on January 6th, where he was quite literally in the process of breaking the law. Thus, these symbols–a mix of American patriotism, white supremacy, and primal battle–have become indelibly linked in people’s minds to “resistance” or “counterculture”. In the same way that Girl Defined’s deployment of aesthetics is intended to appeal to young girls whose self-worth is tied up in their ability to perform traditional femininity, Jacob Chansley’s aesthetic and those like it are meant to attract young men whose self-worth is linked to the ways in which they can enact hegemonic masculinity. Both tactics prey on common gendered fears: for women, who are told their worth is in their conventional attractiveness, the fear of physical ugliness; for men, who are told their worth is in their prowess and their ability to fight, the fear of physical weakness.

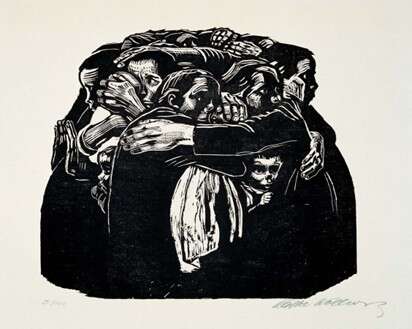

The ways in which traditional masculinity and traditional femininity are enacted, in the context of white nationalist far-right Christofascism, are by necessity opposite. In the fundamentalist Christian worldview, these binaries are complementary, and as elements of an oppressive hegemony, the same is true. Without women inhabiting traditionally feminine roles, men inhabiting traditionally masculine roles would lose their hegemonic power. With this in mind, it is imperative in the minds of Christian nationalists to not only reinforce this binary, but to ensure its continued authority. What better way to achieve this with a young audience than to present its ideologies as rebellious? To appeal to young internet users’ desires for visible cultural clout? To speak their language–that is to say, the language of easily-disseminated memetic images and aesthetics? With this said, the purpose of this paper is to not just shine a light on the recruitment tactics of Christofascist groups–an endeavor I’m hardly the first to undertake–but to offer what might be done to counteract them. I do not, unlike Jonathan Crary in his book Scorched Earth: Beyond the Digital Age to a Post-Capitalist World, believe that the internet is useless as a tool of resistance, or that it should be written off as the domain of reactionaries and self-interested capitalists. As Mike Males points out in his article “Smartphones and Social Media: Why Not to Curb Kids’ Social Media Access”, the internet is a space of crucial importance to vulnerable and marginalized young people, including “girls and LGBTQ youth” (Males 2024). In the same way that the internet can serve as a vehicle for the dissemination of fascistic belief systems and disinformation, so too can it serve as a site for defiance. As such, aesthetics, though a long-time aid in the push toward fascism, can also serve as sites of resistance. Consider the numerous kinds of queer aesthetics gaining ever more traction in the popular consciousness–we might, for instance, use drag performance as just one example. In addition to being an artform unto itself, the political dimensions of drag as a form of resistance to heteronormative constraints are inescapable. Along these same lines, artistic movements and aesthetics that centre creators of colour are not only expressions of diverse cultural backgrounds, but also vital loci of resistance to white supremacy. These spaces are–and always have been–the true sites of rebellion, and the more room we give them, the less we are giving to the same stale, reactionary ideologies re-packaged as “counterculture”.

Works Cited

Beal, Bethany and Kristen Clark. Girl Defined: God’s Radical Design for Beauty, Femininity and Identity. Baker Books, 2016.

Beal, Bethany and Kristen Clark. Project Modesty: How to Honor God with Your Wardrobe While Looking Totally Adorable in the Process. GirlDefined Ministries, 2015.

Birkett, Tom. “US Capitol riot: the myths behind the tattoos worn by ‘QAnon shaman’ Jake Angeli.” The Conversation, January 11, 2021, https://theconversation.com/us-capitol-riot-the-myths-behind-the-tattoos-worn-by-qanon-shaman-jake-angeli-152996.

Crossley, James. “The Apocalypse and Political Discourse in an Age of COVID”. Journal for the Study of the New Testament. Vol. 44, no. 1, 2021, pp. 93–111.

Eco, Umberto. “Ur-Fascism”. New York Review of Books, June 22, 1995. Males, Mike. “Why Not to Curb Kids’ Social Media Access.” LA. Progressive, September 3, 2024, https://www.laprogressive.com/education-reform/smartphones-and-social-media

Read more at By Meg Braid.

Articles, Resistance, Social JusticeRelated News

News Listing

By Rosemary Kasiobi Nwadike ➚

Feminist Miseducation in the Afro-West: Examining (In)Formal Gender Indoctrinations

Articles, Education, Resistance, Social Justice

July 11, 2025

By Joban Sihota ➚

Natural disaster and civic literacy— Language acquisition in the wake of DANA

Articles, Cultural Pedagogy, Education, Public Education

July 8, 2025

By Alexis Andrade ➚

Radical Love: A Revolutionary Force for Liberation

Articles, Cultural Pedagogy, Resistance

June 26, 2025