At the Base of Babel: Language as a Colonial Weapon and Revolutionary Tool

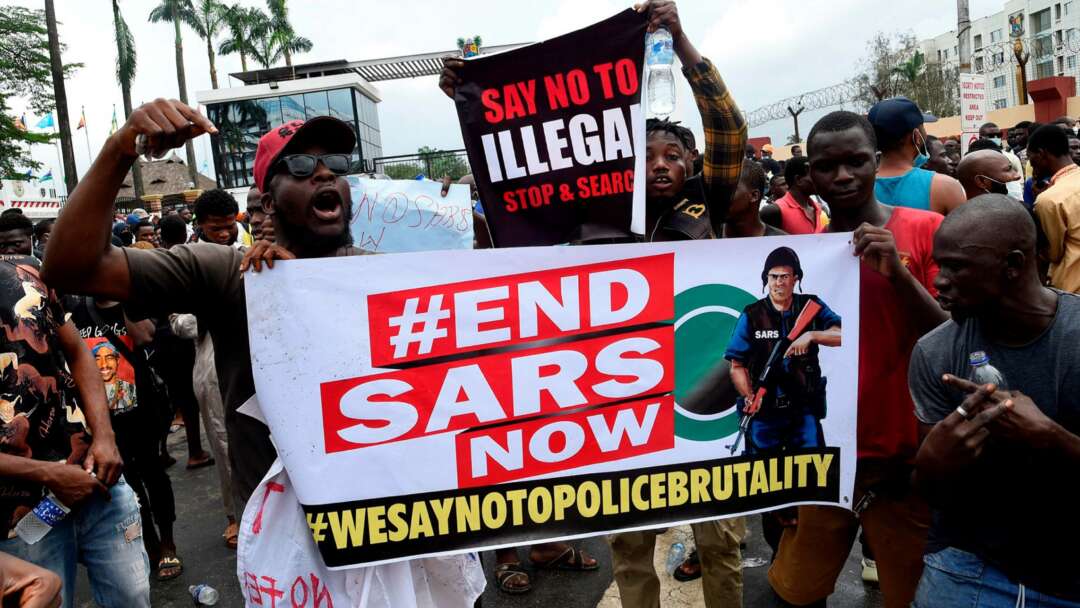

In 2023, for the first time in my adult life, I was excited to participate in the Nigerian presidential elections. At 29, I had already been eligible to vote in two previous presidential elections, but this was the first time I felt a genuine sense of hope. I was not alone in this excitement; all over Nigeria, young people appeared to have one voice for the first time in their living memory[1]. It is crucial to mention some underlying catalysts for this nationwide awakening. The 2023 election came hot on the heels of the historic 2020 #EndSARS protest against police brutality. The protest ignited in the southeast and swept across the nation like wildfire, only to end in a brutal massacre at the Lekki Toll Gate, where the Nigerian Military gunned down unarmed protesters, holding the national flag and singing the national anthem[2].

Far from silencing us, this tragic episode galvanized a collective yearning for change. In 2023, that yearning found its focal point in Peter Obi, a presidential candidate who symbolized hope for a break from Nigeria’s entrenched political oligarchy. Unlike the usual candidates, Obi’s governance record in Anambra State demonstrated integrity, accountability, and a willingness to engage directly with citizens[3]. Secondly, Peter Obi appeared to be a man whose source of wealth is not shrouded in mystery[4]. All these qualities resonated with a populace weary of the corruption and empty rhetoric synonymous with previous leaders and some of the leading contestants.

Nevertheless, my excitement and the broader political awakening of young Nigerians are not the primary focus of this paper. Instead, I aim to explore the conditions that make it possible for a nation’s military to open fire on unarmed citizens. I argue that this troubling reality is rooted in Nigeria’s identity as an internal colonial state, a construct sustained by a language of division that amplifies ethnic and religious differences. I will further examine how this divisive language is propagated through key pedagogical apparatuses – like education systems, cultural narratives, and media discourses – that normalize oppression, entrench state violence, and implicate the people’s participation in their own colonization. Finally, I will propose how these same tools can be transformed to dismantle the colonial state and build a more inclusive and equitable society.

INTERNAL COLONIALISM AND THE COLONIAL STATE

Despite the eagerness in some quarters to pronounce colonialism dead and archive it as history, there are attempts to understand some of the relations that exist within previously colonized countries as operating upon the same premise as colonialism. I do not speak of the external intrusions of Europe and the west in the affairs of other nations; such covert meddling falls under the purview of neocolonialism. I speak, instead, of an internal colonial system that operates upon the premise that a particular demography is valuable while a vast majority of the people are disposable. The internal colonial model was originally propounded around the 1960s in the United States to understand “America’s unwillingness to extend to her racial minorities the same privilege enjoyed by white Americans”(Liu, 1347). This model appears to thrive only in places where the classical form of colonialism existed in one form or another. For America, the settler colonialists who took the land from the native peoples, as well as forceful relocation of black people through the trans-Atlantic slave trade, created the binary of the valuable and the disposables. In former colonies where independence was achieved, a new internal colonial power entrenched itself in the form of the political elite. At the same time, the populace were relegated to the unofficial status of the colonized.

In Nigeria, for instance, it is easy to assume that the legal status that declares every citizen equal renders the question of a colonial state moot, but this is far from the truth. While everyone possesses the same rights under the law, the law has been skewed to allow a specific demography more powers than it accords others. This selective enforcement of the law is why, in recent memory, we have seen a first lady arrest a private citizen over social media post[5]. It is this disposability that empowered the army to open fire on unarmed protesters at the behest of someone whose name has never come out into the open, someone who deemed all those young people disposable (George, par. 1).

Liu referenced a variety of political structures deployed to maintain political dependency amongst Chicanos in the barrio; these machineries often act to subvert and muzzle the will of the people (1353.) Among the apparatus discussed by Liu, I will focus on three very similar tools that apply to the Nigerian situation, “force, intimidation, and disenfranchisement,” and how they show the structures at work in our pseudo-democracy. Every Nigerian election circle since the 1999 reversion to democracy has been marred by electoral violence. Often, young people are weaponized in this struggle to retain power. In a nation where a more significant percentage of the people live below the poverty line, it is easy to purchase loyalty and set the polity against one another. Consequentially, power reverts to the group able to unleash the most chaos.

I am particularly interested in the idea of disenfranchisement. Political apathy has risen over the past two decades until the recent spark of reawakening because people have come to believe that voting matters very little. This belief is borne out of concrete evidence of vote manipulations, tampering, voter suppression, vote buying and a variety of anomalies that attend most elections in Nigeria. In certain areas, few people often vote in a locked room. (Dada, 24) In 2023, while I stood in the queue waiting to vote, a barrage of gunshots tore through the air, and I scampered into the bush with everyone else. While I watched, a group of men walked into the chaos, picked up the ballot papers and boxes, and went into the hall to continue voting on our collective behalf. Voter intimidation in this manner is a common motif: the police and military personnel tasked with protecting the interest of voters and their votes stood motionless, watching the people’s voices get muzzled, as is always the case.

Young people at voting centers were excited at the turnout nationwide, and an evident camaraderie was visible for everyone following the proceedings. An iconic video of young people singing Obi’s name as his votes were counted in a particular polling center in Lagos state circulated through social media. We were all caught up in the frenzy of possibilities, yet numbers have been chalked off by the time these votes arrived at the collation centers or changed so brazenly that it would make you weep. The Independent Electoral Commission (INEC), the body tasked with conducting the general elections led by Mahmud Yakubu, had promised that all votes would be uploaded to the INEC Result Viewing Portal (IREV) platform(6). Yet, on election day, their agents claimed in several places that they could not make the upload. The network suddenly malfunctioned, and vote collation had to be done manually. This disenfranchisement did not require shots to be fired, it simply needed a capture of the nation’s judiciary.

LANGUAGE AND DEVISIVE PEDAGOGIES

Nigeria is a country that is populated by people of diverse ethnicities, languages, and cultures. It is a veritable tower of Babel, which, in some ways, explains the failure of the country to live up to its often-used moniker, giant of Africa. At the last count, there are 250 different ethnic groups in Nigeria and just about enough religious beliefs to ensure divisive topics are always at the service of the oppressors. During every election cycle, the dominant conversation that attends both online and offline spaces are not focused on constructive issues like the track record of the candidates or their humanity or lack thereof; instead, there’s a focus on the individual’s ethnicity and religious affiliation and the fear of domination by one region or the other.

It is easy to incite these divisive topics in a world made extremely small by social media and the internet. Influencers and rabble-rousers employed by the political elite would ignite the fire of ethnic debate with minimal effort. Sometimes, the politicians go as far as brazenly stroking these ethnic flames, as seen in 2023 when the current president, Bola Ahmed Tinubu, ran on the mantra “emi lo’kan” which translates to “It is my turn.” In one press event, he explicitly said, “It is the Yoruba’s turn to rule, and if it is the Yoruba’s turn, then it is my turn!” (Akinyemi, par. 5). On social media platforms, Igbos and Yorubas engaged in an endless back and forth not about who is fit to rule but which region should.

In Lagos state, the gubernatorial candidate of the Labour Party, Gbadebo Rhodes-Vivour, was said to be of mixed heritage with an Igbo mother and a Yoruba father. For most people, his parentage meant that he was not Yoruba enough to be the governor of Lagos state (Ogundamosi, par. 3.) Fearing that the Igbos were poised to foist one of theirs on the metropolitan city of Lagos, this ethnic rivalry intensified and culminated in rhetorics that are not just damaging at that moment but escalated in ways that continue to exacerbate the already tenuous unity of the country. The election in Lagos State was marred by electoral violence worse than the presidential elections that occurred weeks before.[6]

The ease with which many Nigerians descend into divisive rhetoric raises questions about our humanity and values. It reveals a troubling absence of what Paulo Freire calls “critical consciousness” (28), the reflective awareness of social and political contradictions, and the active engagement necessary to transform them. This lack of critical consciousness ensures that the dehumanized remain unaware of their dehumanization and the forces responsible for it. Instead, they humanize their oppressors – those who benefit from systemic inequities – and misidentify the co-oppressed as the root of their struggles. Such dynamics underscore the failure of both cultural and formal education to foster a sense of shared humanity, opting instead to entrench ethnic and racial divides that undermine the common good. Rather than reiterate the widely critiqued shortcomings of the country’s educational system, I will focus on the cultural practices we collectively reinforce and the oppressive apparatuses perpetuating these divides.

The family unit remains the first point of pedagogy. Children absorb what they see, hear, and experience within their immediate surroundings. Parents traditionally spend the most time with their children and are naturally the foundation of a child’s moral and intellectual formation. Yet, this foundation often falters. Fixated on work or overwhelmed by other responsibilities, many parents miss the delicate balance required to effectively shape their children’s character. As a result, children spend more time with teachers, who rarely offer much outside the prescribed party lines of formal education. Yet even this assumes that Nigerian parents possess a unique capacity for objectivity and an understanding of shared humanity that might be missing in teachers. Both assumptions crumble under closer scrutiny, revealing more profound systemic flaws. Looming over these personal influences is a more extensive, insidious pedagogical tool that dismantles individual efforts and breeds division on a broader scale – the media. Beyond the fractured family unit and the failings of formal education, the media as a cultural machinery continues to hold the most significant sway as a pedagogical tool.

In all its iterations, the media has functioned as a powerful pedagogical tool in forming a general cultural attitude. When I speak of the media, I include social media and all forms of news media currently filling the minds of young and old people with misinformation, half-truths, and divisive ethnic rhetoric. This media, particularly the news media, utilizes language in the service of the political elite to create a cultural amnesia that allows for despots, inhumane leaders, and corrupt politicians to step into power every election cycle.

Ideally, the news and other information agencies exist to serve the people. The information they disseminate should be objective and factual, yet the opposite is the case; most media houses in Nigeria exist to serve at the whims and caprices of the political elite. This is hardly surprising given that many of these media houses are privately owned or funded by the same individuals and entities seeking to hold the nation in a constant chokehold. Apuke noted that the internal colonial Nigerian government controls 70% of news media in Nigeria, while only 30% of it is privately owned (4). This media ownership is further complicated by the fact that private owners are either overtly or covertly partisan. The vast majority, particularly the older generation, has been lulled into a false sense of trust in the press, and the younger generation, who possess a healthy suspicion, lack the critical awareness necessary to subvert the lies. Over time, lies have taken on the cloak of truth and vice versa. Unmasking the imposter requires that the polity peer closely at every piece of information, every suggestion, and every bit of news. A critical stance must be taken at every turn to thwart the nefarious plans of a corrupt press.

REIMAGINING BABEL: LANGUAGE AS A REVOLUTIONARY TOOL

The truth for the oppressed lies in the understanding that, while freedom may slouch, it ultimately arrives. History has shown this with every marginalized group in the world: a time comes when the oppressed rise and cast off the yoke of their oppressors. The more difficult reality for the dehumanized is that while freedom must necessarily arrive, the task of unyoking must be undertaken by the oppressed.

Federick Douglas employed the words of the British poet Lord Byron, to show clearly how liberation for the oppressed must arrive: “Who would be free themselves must strike the blow” (par. 3.) Paulo Freire echoes this sentiment, asserting, “This, then, is the great humanistic and historical task of the oppressed: to liberate themselves and their oppressors as well.” (34.) This truth raises a pressing question: how can Nigerians, suffering under an internal colonial system, unshackle themselves from their oppressors?

The 2020 #EndSARS protest has allowed us to glimpse the possibilities for mobilization. The organic nature of the mobilization continues to excite well-meaning Nigerians who hope for a further complication of the relationship between the oppressor and the oppressed. New Media served as a powerful public sphere where the oppressed could trade stories of their oppression and their subtle acts of rebellion. It had begun in Asaba, Delta State where members of the SARS group had gunned down yet another young man without reason; suddenly, young people were rallying in Benin, in Lagos, in Port Harcourt and in all Nigerian cities big or small. On X, people were sharing videos of progress, pictures of defiant young people tired of the status quo. There was no room for the traditional media to steal into the narrative with lies and half-truths, the young people took up the responsibility not just to speak truth to power, but to make sure their truths were not distorted to fit any official narrative.

The beauty, and possibly the undoing of this organic movement, is the lack of a focal point. As the movement gathered momentum, unscrupulous elements and pseudo-activists attempted to position themselves at the head of the movement. This is the often-used tactic of the elite, to position their stooges at the heart of any dissenting movement. It is the house-nigger motif playing out far away from the plantations. There is very little room to discuss these bad faith players who attempted to position themselves as messiahs; I will instead pay attention to the pedagogical and revolutionary possibilities manifest through this organic act of dissention.

One of the first things evident in the movement was that it lacked divisive rhetoric. Instead, it built itself upon a language of collective suffering and a collective desire to be heard. The most popular words from the protest were the Yoruba words “Soro soke!” meaning to “speak out!” These words came to dominate the protest in such a fundamental way that a movement which began as a protest against police brutality morphed into a protest against general government excesses. People were encouraged to speak out and let their pain be known and everyone complied without questioning what language was at the base of the movement or who led it. This is a picture of what is possible when the oppressed eschew divisive rhetoric and push forward with one mind towards a collective goal. This movement wasn’t about how different we were but about the collective pain and who inflicted it – the real enemy was unmasked for all to see.

In her 1993 Nobel speech, Toni Morrison touched upon the need to find common convergence points even when our languages differ instead of pursuing the utopia of a single language (17). She locates the failure of the builders to complete the tower of Babel in their stubborn refusal to acknowledge their differences, in their stubborn desire to speak one voice instead of trying to understand each other. There are over 250 ethnic groups and languages in Nigeria, and too often, the elite magnify the differences to keep the polity divided. What if we refuse to be divided? What happens if we choose to find similarities and not the differences?

Peter Obi mounted a fight for the presidential position that had never been seen by anyone outside Nigeria’s two major political parties, but he ultimately failed. Not because he didn’t win the people’s hearts, not because the ballot had already been bought and paid for before the elections began, and not because the judiciary was a gathering of vultures. He lost because this freedom must come slowly. #EndSARS was the first wave, Obi’s inexplicable offensive was the second, and now, something is in the water. The oppressed have tasted what it means to be free. Paulo Freire believes the oppressed is afraid of freedom for fear of the radicalizing effect; yet, there is a feeling that the future belongs to the oppressed of Nigeria.

[1] The 2019 presidential election witnessed the lowest voter turn out since the return to democratic leadership in 1999 but 2023 witnessed a resurgence not just in voter registration but in the number of young voters with a third of the registered voters falling into the youth category. Festus Iyora documented this for Aljazeera https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2023/2/13/how-nigerian-youths-are-galvanising-for-the-presidential-vote

[2] Ambimbade et al. documented the movement from the murder of a boy in Delta State to its deadly culmination at the Lekki Toll Gate.

[3] Ude, et al. detail some of Peter Obi’s achievements particularly in the educational sector and the methods employed during hit time as Anambra State governor. See “Anambra State Educational Rebirth – The Peter Obi Model.

[4] Bola Ahmed Tinubu, the presidential candiate of the All progressive Alliance was accused of falsifying his academic credentials and complcity in a drug related offence in the United States. See https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2023/10/26/how-a-certificate-scandal-almost-upset-tinubus-presidential-win-in-nigeria , https://www.pulse.ng/articles/news/politics/a-drug-baron-has-won-election-in-nigeria-atiku-quotes-newspaper-2024072608171733351 Atiku Abubakar, the candidate of the People’s Democratic Party has been part of previous governments with corruption charges hanging over his shoulders. See https://www.vanguardngr.com/2020/09/busted-us-places-atiku-family-under-close-watch-over-alleged-fraud/

[5] Aisha Buhari, the wife of former president Muhammadu Buhari arrested a twitter user for saying she grew fat after spending Nigeria’s money. see https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-63854699

[6] In the wake of the dogwhistles that attended Gbadebo Rhodes-Vivour’s candidacy, there appeared to be a renewed hate for people of Igbo descent living in lagos state, a sentiment which some people believe extends beyond lagos to the nation at large. See Jephthah Elochukwu Unegbu’s “Igbophobia in Lagos and Nigeria 2023 Elections:Myth or Reality

Works Cited

Abimbade, Oluwadara et al. “Millennial Activism within Nigerian Twitterscape: From Mobilization to Social Action of #ENDSARS Protest.” Social Science and Humanities Open, vol. 6, no. 1, 2022.

Akinyemi, Boluwatife. “It is My Turn, It is Yoruba’s Turn – Tinubu.” Nigerian Tribune, 3 June 2022.

Apuke, Destiny Obieriri. “Media Ownership and Control in Nigeria: An Overview of Marxist and Pluralist Theories.” New Media and Mass Communication, vol. 54, 2016, pp. 31-40.

Dada, Omoniyi John. “A Holistic Appraisal of Electoral Fraud and Other Electoral Irregularities in Nigeria: Way Forward.” Global Journal of Politics and Law Research, vol. 9, no. 4, 2021, pp. 21-31.

Douglas, Frederick. “If There’s No Struggle, There’s No Progress.” BlackPast, 1857, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/1857-frederick-douglass-if-there-no-struggle-there-no-progress/.

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 30th Anniversary Edition. Bloomsbury Academic, 2014.

Ishaq, Khalid. “Nigerian Student, Aminu Adamu Mohammed Apologizes to Aisha Buhari Over Tweet.” BBC, Dec. 2022.

Iyora, Festus. “How Nigerian Youths Are Galvanizing for the Presidential Vote.” Aljazeera, Feb. 2023.

Lawal, Shola. “How Certificate Scandal Almost Upset Tinubu’s Presidential Win in Nigeria.” Aljazeera, Oct. 2023.

Liu, John. “Towards an Understanding of the Internal Colonial Model.” Postcolonialism: Critical Concepts in Literary and Cultural Studies, edited by Diana Brydon, Taylor and Francis Group, vol. IV, pp. 1347-1364.

Morrison, Toni. “Nobel Lecture.” Nobel Prize, 1993, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1993/morrison/lecture/.

Ogundamosi, Kayode. “Who is Yoruba? Much Ado About Gbadebo Rhodes-Vivour and His Igbo Heritage.” The Cable, 7 March 2023.

Shotayo, Nurudeen. “A Drug Baron Has Won Elections in Nigeria – Aticku Quotes Austrian Newspaper.” Pulse Nigeria, March 2023.

Unegbu, Jephthah Elochukwu. “Igbophobia in Lagos and Nigeria 2023 Elections: Myth or Reality.” Amamihe Journal of Applied Philosophy. Vol 21(4) 2023.

Udeh, Chigozie et al. “Anambra State Educational Rebirth – The Peter Obi Model:” An Education Policy Assessment Report,” 2018.

Vanguard News. “US Places Atiku Family Under Close Watch Over Alleged Fraud.” Vanguard News, Sept. 2020.

Yakubu, Mahmoud. “Electronic Transmission of Results.” INECNigeria, 2021.

Read more at By Ozichukwu Chimezie Ifesie .

Articles, Public Intellectuals, Resistance, Social JusticeRelated News

News Listing

By Maya Phillips ➚

Failure to Reeducate: Perpetuations of Cultural Fascism in Post-War Germany

Articles, Cultural Pedagogy, Public Pedagogy

February 9, 2026

By Rosemary Kasiobi Nwadike ➚

Feminist Miseducation in the Afro-West: Examining (In)Formal Gender Indoctrinations

Articles, Education, Resistance, Social Justice

July 11, 2025