Postcolonial Reparative Action: Transnational Memory-Making and Historical Remembrance as Potential Sites for Social Bond Recovery and Practising Global Mnemonic Solidarity

In The Force of Non-Violence, Judith Butler (2020) challenges the audience to rethink the binary and Manichean ways in which we – as a global interconnected society – politically, socially, historically, and culturally interpret, internalise, and ultimately construct frameworks and discourses of “violence” and/versus “nonviolence.” Butler (2020) brings to the surface the fraught semantics behind discourses of violence and nonviolence, and the ways in which unequal power dynamics, racial schemas, and political interests shape notions of who gets to define the fluctuating parameters that constitute violence. Butler (2020) elaborates on how the misuse or co-opting of language can be weaponised as a cognitive tool of domination and subjugation that can serve to obscure how varying typologies of violence are repackaged, repurposed, and [re]perpetuated within and by our social structures, across the past-present continuum.

These are social structures that rely on the normalisation of perceptions around the permanency and ubiquitous nature of the ‘force field of violence,’ which, depending on shifting socio-historical and geopolitical contexts, can work to ‘justify’ structural and institutionalised racial violence as legitimated instruments of ‘self-protection’ and’ self-defence’ by individuals and State agents (Butler, 2020). These perverse and epistemically limited ideas of self-protection via brute force and biopolitical control underpin and characterise the unequal modern colonial world and its necropolitical operational mechanics, which continue to negate the inherent value of lives (human and non-human alike) in the name of domination/subjugation, surplus material accumulation, hyper-exploitation, systemic dispossession, and an entrenched process of Otherisation/dehumanisation for the purpose of maintaining the hierarchical racist colonial world order; a world order that delineates in the logics of ‘grievable’ and ‘non-grievable’ bodies and lived experiences (i.e. those considered fully human and deserving of life and non-humans who become permanently subject to various iterations of violent powers, structural abandonment, and political negligence) (Butler, 2020).

Butler (2020) notes how forms of violence are routinely re-imagined, renamed and re-semanticised as nonviolent by States, highlighting the critical need to intellectually expand ideas of violence beyond the visible “figure of the blow” (pg. 11) in order to both clarify what violence is and account for more insidiously invisible manifestations of systemic and structural violence perpetrated by our legal, political, and economic systems (e.g. institutional racism and racist policy making). Butler (2020) argues that these limited conceptual mappings of violence and nonviolence, which are often posited as sitting on opposite sides of a spectrum, are rooted in a common neoliberal framework shaped by biopolitics and biopolitical power. This limited framework is then mobilised and sustained by a harmful individualistic paradigm that often abdicates its social responsibilities and reneges on the contractual ethical obligations related to the intimate moral, ecological, and social bonds inherently defining us within the political economy of global violence, human misery, and [well]-being.

Therefore, Butler (2020) argues that in order to effectively recover the interdependent Self, each other, and other alternative performances/productions of social being based on “an egalitarian approach to the preservation of life” and a “radical democracy” (pg. 55), the political practice of nonviolence offers a necessary avenue towards re-imagining and re-interpreting ideas of violence in ways that co-produce a useful political action that vigorously rejects notions of social exclusion and alienation. In doing so, this allows us to cognitively and psycho-socially co-construct an “altered state of perception, another imaginary, that would disorient us from the givens of the political present” (Butler, 2020, pg. 50). However, an important element of Butler’s (2020) argument pertains to the fact that a realistic form of nonviolence “requires a critique of what counts as reality, and it affirms the power and necessity of counter-realism” (pg. 17), and in order to manifest and fully operationalise nonviolence, we must first “ask what violence destroys” (pg. 22). We must “situate violent practices (as well as institutions, structures, and systems) in light of the conditions of life that they destroy” in order to uphold certain ‘realities.’ This helps us to figure out why we should even care to recover the social bonds that have been under relentless attack by violent powers across space and time (Butler, 2020, pg. 22).

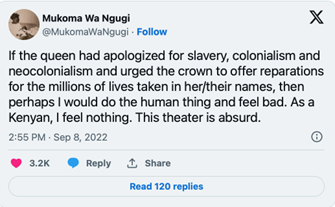

The next part of the paper asks whether or not sites of violent historic encounter, transnational remembrance, and memory making offer spaces for nonviolence and “global mnemonic solidarity”[1] to flourish in ways that can help us to recover and disentangle our fragile social bonds from violent powers. How can nonviolence as a political action create spaces for new avenues of global mnemonic solidity, justice, and radical egalitarianism? It begins, as Butler (2020) purports, from the standpoint of critiquing what is and should count as reality, and this critique is borne out of the critical imperative to understand the shared historic complexities that have shaped our co-constitutive social realities and material conditions. I argue that how we remember and re-remember the numerous human tragedies and traumas sitting rife in our intertwining pasts and collective memories within the global memory sphere is an important first step to salvaging the social bonds; bonds that we deserve and crave but have been so viciously robbed of. To further navigate this question, we can consider the death of Queen Elizabeth II and the politics of memory, and how revisionist history and social amnesia work to rebrand imperial violence in the fragmented ‘post’-colonial era. In September 2022, Queen Elizabeth’s death sparked renewed conversations around the legacies of British imperialism and colonial exploitation. Two competing and diametrically opposed histories and narratives emerged: one of nostalgia, empire apologia and a romanticised revisionism, and the other of a deep sustained intergenerational trauma that continues to “mourn the lives lost, [recount the worlds destroyed] and heal from the collective pain under [violent] colonial rule” (Walton, 2022).

In its communications, the BBC used the words “long standing relationship” as a euphemism for the centuries-long colonially entrenched relationship between Africa and the British monarchy, one rooted in brute force, imperialism, wealth extraction, disposability, and unimaginable forms of oppression. Here we can see how mainstream legacy media is a colluding entity that manufactures public consent for the breeding and consecration of violence through its weaponisation of a language that works to exonerate the enactors of state-sanctioned violence. Queen Elizabeth II’s death and the discourse around how we as co-existing societies remember ever-present colonial legacies has brought to the forefront how the politics of transnational memory is not only a site of political struggle, but a charged space that holds the potential for nonviolence as a political action. In this example, instead of expecting uniform mourning among the former colonies and their colonial masters, this event could have opened real possibilities for nonviolence as a viable means of resistance through acknowledging differential histories of ongoing violence. Realistic nonviolence as a postcolonial reparative action in the present can only be practised when violent histories and presents are acknowledged, otherwise it remains utopic at best and at worst, its unrealism falls prey to yet more forms of political theatre/ performativity.

Globalisation in many senses has transcended what we have previously known to be traditional borders and their conceptualisations as impenetrable containments of national memory (Jie-Hyun Lim, 2019). Therefore, Queen Elizabeth’s death was an important moment of rupture that gave us a real opportunity to discuss the damaging impacts of whitewashing history and symbolic violence, and how this cleansing and clinical sanitisation contributes to a kind of intentional social amnesia that upholds the violence of white supremacy as a neo-colonial apparatus. The increasingly perforated nature of the global memory space has allowed for national political stories and histories (and revisionist myths) to become more entangled and challenged by various actors, which gives memory and spaces of historical narrative reclamation the ability to truly reckon with the social bonds and “conditions of life and livability” that colonial violence has destroyed (pg. 22).

Because the politics of memory now takes place in a world arena versus a national stage, previously “unconnected historical actors” can effectively challenge how we remember, presenting a site of narrative re-negotiation, reconciliation, and amalgamation of our social bonds through the participation of a broader set of actors and perspectives in history-making (Jie-Hyun Lim, 2019). The Queen’s death and the attempted rebranding of the monarchy from global death machine to a post-colonial abstract entity with minimal responsibility for adequately addressing or taking responsibility for its past violent transgressions showcases the importance of truth (historical accuracy) as a vehicle for birthing windows of opportunity to salvage our interdependence. These new formations and actors, alongside the reconstitution of fractured social bonds, make way for new [nonviolent] interventions that can address the long-lasting historical harms and cultural violence(s) that hold/reflect similar underpinnings of the modern colonial racial world.

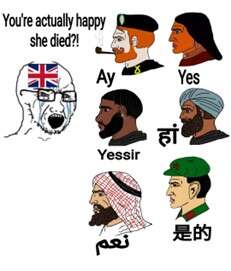

For those of us outside of imperial and nationalist British ideology, colonialism is not a singular historic event, but an ongoing project and process that continues to define the world through violent power, epistemic injustice, and historic erasure. As such, historic context would make the particular moment of the Queen’s passing more understandable without the assumption that billions of Black and Brown people around the world were being disrespectful/rude/hostile to Queen Elizabeth, or insensitive to those of British nationality. Memory appropriation occurs when actors take stills or snapshots of historic moments of violence, such as those embedded in legacies of British colonialism, and project them without full context. This can fuel the rise of bad faith political actors that co-opt specific properties, characteristics, and symbols (of genocidal, oppressive, violent or fascist leaders and their ideologies), adopting them into the present without context or acknowledgement via the process of selective remembering/memory-making.

This is what allows for the co-opting of violent narratives under the guise of ethnic nationalism and collective “grief.” It is here that transnational memory, as a result of the de-nationalisation, depoliticisation, and de-territorialisation of historical narratives taking place in the [intergenerational] global memory space, becomes a site of alienation, the further breaking of social bonds, and the reproduction of oppressive world structures and regimes, rather than a space of building global mnemonic solidarity and recovering a social interdependency that aggressively recognises/protects/defends the intrinsic value of all life. Therefore, a pertinent question becomes: how does nonviolence fit within a context that vehemently denies its own violence, and yearns for a past rife with violence and inequity as a result of an empire nostalgia that both appropriates symbols, rhetorics, and memories, and has become synonymous with racial domination and racist nationalism?

If we cease to talk about colonialism as an ongoing project and refuse to exorcise its mutating violences from our social bonds, then we rescind our right to live in the hopes of alternative nonviolent imaginings outside the current exploitative arrangements and expressions of Western ideological power, colonial gazing, and imperial knowledge production that seeks denial/obfuscation rather than a “postcolonial reparative action” (Bhambra, 2019). We willingly resign ourselves to becoming passive, non-agentic subjects that submit to a world of ‘naturalised’ violence and continue to become part of a violent world that severs rather than nurtures our social bonds. Parallel realities and truths that run alongside whitewashed and sanitised forms of history indicate a very different cultural and symbolic meaning regarding the Queen’s death, and the still prevalent legacies of British colonial history. For the oppressed around the world, the death of one of the world’s longstanding monarchs and her commitments to colonial violence is a symbol of hope, opportunity, expanded imaginaries, and new possibilities of nonviolence through a counter-realism that can finally uproot colonial mythologies, structural violence, and global inequalities.

Therefore, in 2022, oppressed and marginalised communities globally vehemently rejected the expectation that they should universally mourn their coloniser under the guise of “respect,” “diplomacy,” and “civility,” and refused to be bound by colonial time in the so-called “post”-colonial era. This underlying tension punctures the intellectual and ideological façade of the “post”-colonial as an assumed space with materialised human rights for all and highlights the various ways in which States and their agents continue to use public semantics to rehabilitate the field of violence and violent powers that “establish the unequal worth of lives” and devalue the different lived experiences of populations “by establishing their unequal grievability” (Butler, 2020, pg. 21). As Butler (2020) argues, nonviolence as a philosophical paradigm should be understood as “a social and political practice” (pg. 21) and as an unrelenting yet always unfinished “ongoing struggle” (pg. 23) within material and social realities under constant critique and [re]construction; critiques and reconstructions working consistently to aggressively recover our interdependent social bonds. It is only within a political action that recognises transnational memories across diverse geographies, that our relational obligations as an interdependent global community with radical cooperation can become fully realised and operationalised.

[1] Jie-Hyun Lim (2019) writes that the “global memory space has emerged to challenge the nation-state as the legitimate container of collective memories”, and therefore global mnemonic solidarity becomes defined as theoretical and political process whereby “the extraterritoriality of remembrance” exposes previously “unconnected historical actors and memory activists” to each other in ways that create new avenues for transnational solidarity and social interventions for global accountability.

Works Cited

Bhambra, G. (2019, August 9). Professor Gurminder Bhambra – History matters: Inequalities, Reparation and Redistribution. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BDSUuw0-EWk

Butler, J. (2020). The force of nonviolence: An Ethico-political bind. Verso.

Lim, J.-H. (1993). Mnemonic Solidarity in the Global Memory Space. The Global-e Journal , 12(4). https://globalejournal.org/global-e/january-2019/mnemonic-solidarity-global-memory-space Walton, A. (2022, September 22). 70 years on mau mau history reminds us of the british monarchy’s violence. THE NEW ARAB. Retrieved from https://www.newarab.com/opinion/mau-mau-70-years-british-monarchys-violent-role.

Walton, A. (2022, September 22). 70 years on mau mau history reminds us of the british monarchy’s violence. THE NEW ARAB. Retrieved from https://www.newarab.com/opinion/mau-mau-70-years-british-monarchys-violent-role

Read more at Lulwama Mulalu.

Articles, Public Pedagogy, Resistance, Social JusticeRelated News

News Listing

By Rosemary Kasiobi Nwadike ➚

Feminist Miseducation in the Afro-West: Examining (In)Formal Gender Indoctrinations

Articles, Education, Resistance, Social Justice

July 11, 2025

By Joban Sihota ➚

Natural disaster and civic literacy— Language acquisition in the wake of DANA

Articles, Cultural Pedagogy, Education, Public Education

July 8, 2025

By Alexis Andrade ➚

Radical Love: A Revolutionary Force for Liberation

Articles, Cultural Pedagogy, Resistance

June 26, 2025