The Ungrounding of Humanity: Sustainable Energy Discourses and the Plunder of the Earth

Introduction

Wide-scale environmental disaster is not coming—it is already here. The question of how to mitigate it is pressing, and yet we continue to extract natural resources through logging and mining on a massive and wasteful scale. In this context, I will connect the idea that capitalism acts as a disembodying and dissociative force with the idea that environmental degradation through resource exploitation alienates people from their relationship to the land. Ultimately, this results in both a literal and figurative ejection of humanity into outer space. I will analyze these ideas through two seemingly separate case studies, one of billionaire entrepreneurs who wish to create extraterrestrial civilizations and one of the exploitation of Bolivia’s lithium in the Salar de Uyuni flats. In placing these case studies next to each other, I hope to show how, using the rhetoric of sustainability and progression beyond fossil fuels, people are in fact being ungrounded from the Earth.

Extraterrestrial Visions: Space Ventures as a Case Study

In his 1971 essay “A Sick Planet,” philosopher and filmmaker Guy Debord wrote on the environmental destruction caused by capitalism through pollution. At one point in his essay, Debord says, within parentheses: “for after all [the masters of society] live on the same planet as we do—which is the only sense in which it may be said that the development of capitalism has in effect brought about a measure of class fusion” (Debord). Andreas Malm makes a similar argument in White Skin, Black Fuel, contending that no concrete action can be done against climate change until we’re all “reduced to cinders”—in other words, black and brown lives matter so little that it is only when environmental destruction affects everyone that true change will happen (320). What both Debord and Malm do not anticipate is that for the infinite plunder of capitalism, for its already disembodied and ungrounded force, it does not matter if the Earth is reduced to cinders. For “the masters of society,” there will always be the stars.

It is well known that Elon Musk envisions a complete transformation of Mars, wishing to colonize it as a viable alternative to Earth’s future destruction (Grind). At first, this move seems strange. The throughline of Musk’s other projects, Tesla and Starlink, hinges on sustainability, ostensibly an effort that implies striving for the continuation of human life on Earth, most often through measures that protect the Earth’s environment. However, Musk’s Martian aspirations follow directly from an attitude toward the environment shaped by capitalist logic. The resources for technology to terraform Mars or establish colonies in space would require a massive plundering of the Earth; in terms of raw materials, and in terms of money and time. Musk knows this, and in fact tailored several of his business moves toward this goal. His tunneling company “The Boring Company” was “started in part to ready equipment to burrow under Mars’s surface,” he bought X “partly to help test how a citizen-led government that rules by consensus might work on Mars,” and his Cybertrucks are a model for the Martian vehicular transport he envisions (Grind). However, his companies still rely on the mass production and consumption of his products, a well of money and resources for him to grow without inhibition. This logic directly contradicts the notion of sustainability in its most basic sense—that is, to sustain life on Earth. The fact that Musk’s businesses have been shaped toward his extraterrestrial goal reveals that Musk’s plan was not to sustain life on Earth, but to be able to sustain life off Earth, eventually without Earth.

That the needs of humanity within a capitalist economic system will extend beyond what can be provided on our planet is taken as a given within the same logic that destroys the planet. In his book Scorched Earth: Beyond the Digital Age to a Post-Capitalist World, Jonathan Crary says that “capitalism necessitates the elimination of whatever might impede or obstruct the physical or immaterial flows intrinsic to capital accumulation” (53-4). What happens when the thing that impedes capital accumulation are the limitations of the Earth itself, the bare fact that material resources are limited on both a temporal and spatial scale? It is important to note that I am not suggesting here that colonizing other planets is a viable idea, nor even that these billionaires feel like it can be achieved during our lifetimes. The science of it is not what is at stake, as regardless of whether or not this is feasible, it still encapsulates a worldview in which the world is not a part of it. This is a path that only goes forward, only furthers environmental destruction. It is a path where healing, recovery, and care are not even in the vocabulary. Musk is not the only billionaire whose vision of humanity’s future involves a total ungrounding from Earth. Jeff Bezos owns Blue Origin, a company with a vision toward space colonies unattached to a particular planet (Chang). Bezos is quoted in the article to have said that “We will run out of energy. This is just arithmetic. It’s going to happen” (Chang) The article then posits that “[a]t that point, to remain on Earth would require rationing and declining opportunities. But the rest of the solar system offers virtually limitless resources” (Chang). Colonizing space, detaching humanity entirely from its Earthly boundaries, is not simply Musk’s or Bezos’s delusion, but a shared ideology of destruction, one that prefers boring holes into the Earth to envisioning a society where people may be connected to the ground on which they stand.

Bill Gates also approaches this ideology through a language of sustainability, particularly salient in his reusable rocket company Breakthrough Energy Ventures. In their publicity statement, they state: “Imagine being able to detect wildfires in any country within minutes, identifying oil and gas methane emissions in real time for remediation, or verifying carbon stocks globally to enable large-scale carbon offset markets” (Boyle). Their core philosophy appears to be to combat climate change through precise measurement, an abundance of data, and careful monitoring. Through this lens, solving issues such as uncontrolled wildfires or skyrocketing carbon emissions comes down to quantitative measurements. Debord points out this type of thinking in his essay, saying that “[f]or bourgeois thought…speaking methodologically, only the quantitative is valid, measurable, and efficient, whereas the qualitative is no more than vague or subjective or artistic decoration of the really true” (Debord). The issues of climate change are reduced to quantitative measurements, problems of instrumentation and adaptive technology rather than structural issues intrinsic to the way that social relations are structured in society. In fact, the environment is not even considered a component of social relations. Rather, it is a supplement to the human capitalist economy, which itself is functionally removed from social responsibility due to the aforementioned necessity to eliminate anything that obstructs capital accumulation.

I said earlier that capitalism is a disembodying and ungrounding force, and I meant for that to be taken in as literal of a manner as possible. When the catastrophe of climate change is abstracted into satellite data, when the richest people on Earth want to remove themselves from the Earth—in Bezos’s case, any planet—entirely, the oppressed classes and nations may literally have no ground to stand on. It would have been burned or bored away. Crary paraphrases Andreas Malm in saying that “for all the demonstrably abstract features which allow the untrammeled mobility of capital, abstract space depends intrinsically on terrestrial resources…The mobility of capital is paradoxically made possible by immobile strata of concentrated energy” (Crary 53; emphasis the author’s). Gates must source the material for the satellites, the servers that house the satellite data, and more, all in addition to the massive amount of space and raw materials go toward his own tech empire. The idea of the company itself, that the way out of climate disaster is through satellite data rather than social change, hinges on the abstraction of sustainability in order to disguise the inefficacy of technical solutions such as this.

Grounding Capital Dreams: Bolivia as a Case Study

Having explored how select billionaires plan to unground humans in the future, I would like to examine a case study to see how humans are being ungrounded from their land now. In November of 2019, Bolivian president Evo Morales was removed from his position as head of state. Ostensibly, he resigned over controversy surrounding his re-election (Prashad). However, it has become increasingly apparent over the past several years that he was forced out due to a confluence of events, not limited to the Organization of American States (O.A.S.), a third-party overseer of the 2019 election, accusing him of fraud despite apparently faulty statistical analysis (Kurmanaev and Silvia Trigo). In 2020, Elon Musk said in a tweet “We will coup who we want! Deal with it!” in response to a tweet that implied Musk would, with the support of the U.S Government, conduct a coup against Bolivia to get a hold of the country’s lithium. Though this tweet is most likely a joke, it does reflect a certain political reality of Bolivia. Bolivia is in the “Lithium Triangle,” a lithium-rich region spanning Bolivia, Argentina, and Chile (Prashad and Bejarano). Lithium is a key resource for the batteries needed in electric cars, and as such several transnational corporations have set their sights upon obtaining land in this region (Prashad and Bejarano). In 2006, the Morales government came into power and took control of several mining operations, nationalizing them along the way (Prashad). Morales also refused to strike a deal with transnational corporations unless they entered negotiations with the national mining and lithium companies, agreements that would fund social programs (Prashad and Bejarano). As a result of this, multiple firms refused to install plants in Bolivia, moving to Argentina instead (Prashad and Bejarano). After Morales left office, a short-lived conservative government led by Jeanine Áñez was installed. Her running mate in the next election, Samuel Doria Medina, wrote in a 2020 tweet that Tesla should “build a Gigafactory in the Salar de Uyuni to supply lithium batteries” (Prashad and Bejarano). The relationship between the right-wing in Latin America and resource extraction is no secret. It is clear here that Bolivia’s nationalized resource corporations stand in a precarious relationship to regime change.

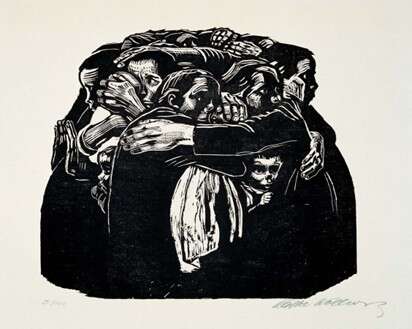

Given this understanding of Bolivia’s lithium industry, I will now examine some of the rhetorical lines framing resource extraction in Bolivia. Leo Löwenthal, in his essay “The Atomization of Man,” says that “[i]n a system that reduces life to a chain of disconnected reactions to shock, personal communication tends to lose all meaning…[both the terrorized and the terrorist] are mere material conforming to situations created by a power utterly independent of themselves” (177; emphasis my own). Although here Löwenthal is discussing the relationship between fascism and terror, it is clear that there is a link between the extraterrestrial projects of billionaires such as Musk, Bezos, and Gates, and the utter devaluation of human life to the material. This penetrates the core of discourses surrounding climate change and green energy, especially regarding a country in the Global South such as Bolivia. In a New York Times article discussing a “small Texas energy start-up” EnergyX and their attempt to break into Bolivia’s lithium energy, the article makes a brief mention of the spiritual connection that the Quechua people indigenous to the Salar de Uyuni held—“their forebears believed [the flats] were the mixture of a goddess’s breast milk and the salty tears of her baby” (Krauss). This paragraph is immediately followed with this: “[w]ith a quarter of the world’s known lithium, this nation of 12 million people potentially finds itself among the newly anointed winners in the global hunt for the raw materials needed to move the world away from oil, natural gas and coal in the fight against climate change” (Krauss). The destruction of these flats is not only framed as progressive, but is also considered a privileged position to be in. Much like how interpersonal connections are reduced to “disconnected reactions” in Löwenthal’s description of fascist terror, human-nonhuman connections also lose meaning. The embodied spiritual connection that the Quechua people have with the flats is left in the dust of technological progress in the name of fighting climate change, but in reality to prop up a system that sees energy needs as infinitely expanding.

This is plainly colonial rhetoric, something which is reflected in EnergyX’s philosophy. The start-up’s founder, Teague Egan, is said to have “never worked in Latin America and speaks virtually no Spanish” (Krauss). The prospect of “green energy,” i.e. the ability to continue accelerating energy usage without bringing on a total apocalypse through climate change, supersedes the relationship that a people may have with the land. This colonial impulse is furthered by Egan’s comments on Bolivia’s politics. Egan says “In Bolivia they are so sensitive about the politics. I just don’t understand why they should not do what is in the best interest of the country. I can only control what I can control” (Krauss). The article supports him in this, saying that “[t]here is much that Mr. Egan cannot control in this country long riddled with coups and racial, ideological and regional divisions” (Krauss). Setting aside this erroneous idea that racial, ideological and regional divisions are somehow not pervasive throughout most, if not all, nations on Earth, it is clear here that this article can be placed within a larger set of discourses that mobilize rhetoric around a country’s political stability to further the uninhibited exploitation of natural resources.

It is possible to simply say that this colonialist rhetoric simply arises from a disconnect from the land. However, I argue that there is something else at work here—the deprivation of senses. In Scorched Earth, Crary paraphrases Lewis Mumford in saying that the consequences of capitalism predicated on resource extraction include “the wounding of sensory and perceptual experience amid the interconnected requirements of war and industrial production” (38-9). Here, “[a] condition of partial anesthesia became necessary for survival” (39; emphasis is mine). Crary discusses this in the context of the environmental destruction that digital media wreaks on society, particularly drilling and mining. What happens when this destruction severs us from the Earth, when longstanding cultural traditions and mythologies must be torn from the landscape and transplanted elsewhere, in order to survive? Yes, it is the case that in order for Musk to further his renewable energy projects (and covertly, his Martian colonization project) he will need to plunder South America. Yet the very idea that he would think to colonize space, to flee the Earth, shows a profound senselessness, literally a lack of senses.

This partial anesthesia, the reduction of human-nonhuman relations to mere material, and the abstraction of the Earth mentioned earlier work together to transform the Earth into a viable point of annihilation. Crary says of global capitalism that “[l]ife, whether of the body, of ecological rhythms, or of social resilience [become] not just an object to be controlled and exploited but to be made into a potential object of extermination” (Crary 55). This ideology is what infects the discourses around Bolivian lithium, even under its socialist government. Alvaro Garcia Linera, Morales’s vice president, “has said that lithium ‘is the fuel that will feed the world’” (Prashad). Under this rhetoric, lithium remains a resource, and by extension, the salt flats a fuel tank. Bolivia has made immense strides in terms of alleviating poverty since the nationalization of several sectors (Bonifaz and Lefebvre), yet I must wonder if and how this improvement can be sustained, and what logic it is operating through. In their book Peasants, Capitalism, and Imperialism in an Age of Politico-Ecological Crisis, Mark Tilzey and Fraser Sugden contend that Morales and Garcia Linera are exacting reformist policies, quoting Forrest Hylton and Sinclair Thomson in saying that they intend to “modify the rules of neoliberal capitalism in favour of a state that would work to improve the welfare of all its citizens, especially the poor rural and urban indigenous majority, through redistributive policies and social programmes” (Tilzey and Sugden 198). Morales and Garcia Linera’s policies walked a fine line between installing genuine welfare initiatives and engaging the extractivist model of economy that dissociates Indigenous Bolivians from their land—a line which I am not always sure deviated enough from the colonialist rhetoric that I discussed above.

Conclusion

I have presented in this essay two radically different moments in politics and culture—the project of certain billionaires to shuttle human civilization off-planet and the iron determination of both transnational corporations and governments to exploit Bolivia’s lithium resources. With the former project, there is an attempt to move humans off Earth, severing their connection to the land in the most literal way possible. For the latter, Indigenous Bolivians are being slowly pushed off of their land and sacred space due to the spatial needs of mining. This transforms the Salar de Uyuni from a site of complex relationships between Quechua people, their beliefs, and their landscape into a resource that can be exploited endlessly by virtue of it being abstracted from its relations—a more figurative ejection from the Earth, and yet still a real detachment from land. I brought these two case studies together to reveal the shared goal of disembodiment and detachment that capitalist and colonialist impulses strike toward, a goal which results in mass environmental degradation. This environmental degradation arises in part from the failure to observe the inherent entanglement of society and ecology. Off-worlding (privileged) humans, believing that climate change issues can be solved through increased measurement, and a disembodiment from the senses are all symptoms of this issue.

Works Cited

Bejarano, Vijay and Alejandro Prashad. “Elon Musk Is Acting Like a Neo-Conquistador for South America’s Lithium.”Peoples Dispatch, 10 Mar. 2020, https://peoplesdispatch.org/2020/03/10/elon-musk-is-acting-like-a-neo-conquistador-for-south-americas-lithium/.

Boyle, Alan. “Bill Gates’ Breakthrough Energy Leads $65M Funding Round for Stoke Space’s Reusable Rockets.” GeekWire, 15 Dec. 2021, https://www.geekwire.com/2021/breakthrough-energy-ventures-leads-65m-funding-round-for-stoke-spaces-reusable-rocket-stages/.

Chang, Kenneth. “Jeff Bezos Unveils Blue Origin’s Vision for Space, and a Moon Lander.” The New York Times, 9 May 2019. NYTimes.com, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/09/science/jeff-bezos-moon.html.

Crary, Jonathan. Scorched Earth : Beyond the Digital Age to a Post-Capitalist World. Verso, 2022.

Debord, Guy. “A Sick Planet.”e-flux, 28 Nov. 2022, https://www.e-flux.com/notes/506238/a-sick-planet.

Grind, Kirsten. “Elon Musk’s Plan to Put a Million Earthlings on Mars in 20 Years.” The New York Times, 11 July 2024. NYTimes.com, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/07/11/technology/elon-musk-spacex-mars.html.

Krauss, Clifford. “Green-Energy Race Draws an American Underdog to Bolivia’s Lithium.” The New York Times, 16 December 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/16/business/energy-environment/bolivia-lithium-electric-cars.html.

Kurmanaev, A. and Silvia Trigo, M. “A Bitter Election. Accusations of Fraud. And Now Second Thoughts.” The New York Times, 7 June 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/07/world/americas/bolivia-election-evo-morales.html.

Lowenthal, Leo. “The Atomization of Man.” False Prophets, 1987. Routledge, 2017, pp. 175-185.

Malm, Andreas. White Skin, Black Fuel. Verso, 2021.

Prashad, Vijay. “Bolivia: An Election in the Midst of an Ongoing Coup.” MR Online. 12 Feb. 2020, https://mronline.org/2020/02/12/bolivia-an-election-in-the-midst-of-an-ongoing-coup/.

Tilzey, Mark and Fraser Sugden. “Bolivia.” Peasants, Capitalism, and Imperialism in an Age of Politico-Ecological Crisis. 2023, Routledge.

Read more at By Malaika Mitra.

Articles, Social JusticeRelated News

News Listing

By Rosemary Kasiobi Nwadike ➚

Feminist Miseducation in the Afro-West: Examining (In)Formal Gender Indoctrinations

Articles, Education, Resistance, Social Justice

July 11, 2025

By Joban Sihota ➚

Natural disaster and civic literacy— Language acquisition in the wake of DANA

Articles, Cultural Pedagogy, Education, Public Education

July 8, 2025

By Alexis Andrade ➚

Radical Love: A Revolutionary Force for Liberation

Articles, Cultural Pedagogy, Resistance

June 26, 2025